The Culture of Landscape

What makes up a landscape? The word landscape derives from the Dutch landschap, meaning “landship.” The term signifies a segment of nature that can quickly be taken in from a single point of view and encompasses the land and everything on it-animals, people, and structures. This informs us that the Western concept of the landscape is not one of untamed nature, but rather it is an artificial assemblage designed to meet human needs for organized, useful and productive space.

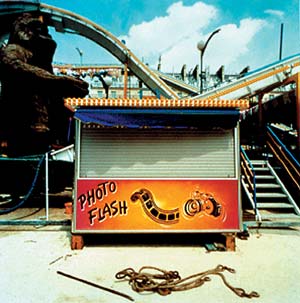

Keith Johnson acts as a visual anthropologist who examines the bizarre and comical banalities of roadside attractions through color, form, and ironic happenstance.

These notions can readily be seen in twentieth century photographs of the American West that have become synonymous with personal freedom and power. People also want a poetic and spiritual symbol that is a tough and wild representation of the American psyche. Photographers have perpetuated this myth so successfully that it has become a leading American cultural export.

In addition, the “good taste” images from Sierra Club publications and Arizona Highways that glorify pristine and unpeopled nature have defined the popular expectations of the landscape. John Szarkowski, former Curator of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, commented that people are thankful to Ansel Adams because his pictures stirred our collective memory of what it was like to be alone in an untouched world. This may be so, but it disregards the reality of how most people experience the landscape.

Today the definition of the landscape includes our past and future cultural expectations. In his book, Why People Photograph (1994), Robert Adams comments: ?If the state of our geography appears to be newly chaotic because of heedlessness, the problem that this presents to the spirit is, it seems to me, an old one that art has long addressed?Art is a discovery of harmony, a vision of disparities reconciled, of shape beneath confusion. Art does not deny that evil is real, but it places evil in a context that implies an affirmation; the structure of the Creation, suggests that evil is not final.”

The landscape is continuously changing, but the basic visual vocabulary that defines it has remained constant. What has changed is how these components are interpreted. The landscape no longer represents the ideal of God’s creation, but is a site to express the personality, ideas, and social/economic/political concerns of the people who live in it. Contemporary communications and mass media have expanded the parameters of the landscape. Concurrent with the writing of this article we witnessed alterations in the American landscape as a result of serial sniper attacks in the Washington DC area.

No longer is the suburban landscape a safe, homogeneous, country-like environment for raising children as depicted by Bill Owens in Suburbia (1973). A horizontal line that once brought together the sky and land in a grandiose manner may now represent the intentions of a sniper’s line of fire. In this extreme case, a middle-class setting that personified the American Dream has become a deranged shooting gallery in which maniacs exercised power by instilling fear. Once insulated and carefree, the anxiety and trauma resulting from such domestic terrorism are causing Americans to alter how they lead their lives. Since 9/11 Americans have been looking over their shoulders at unseen predators, with weapons both invisible and catastrophic, waiting for the next strike that the government tells us is coming. Now average Americans have stalkers, who might shatter their lives while they are doing such daily tasks as opening mail (anthrax), pumping gas, shopping, or eating at a restaurant.

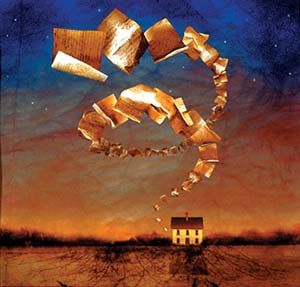

Maggie Taylor reinvents the content, context, and spatial relationships of the landscape by using a flatbed scanner as her camera to form new open narratives.

As the fabric of American society changes so does the response of the photographers who portray it. Even though photographers continue to pay homage to the grandeur of nature, others are specifically examining how the landscape is shaped by human presence, combining and conveying a sense of time, place, and human experience. Their research involves making decisions to include what previously would have been intentionally disregarded for the sake of beauty. Their investigations recognize that through technology and sheer numbers people have become a geological force that shapes the planet’s future just as earthquakes, glaciers, and rivers had altered its past. The monuments and scars of human progress are so common place that we often read the terrain in terms of what is missing—the woods are gone, the freedom to walk where you please has vanished, the horizon is hazy, silence has been shattered, and mysteries are outflanked rather than faced. These transformations leave us with nostalgia for a transcendental landscape that has long disappeared and photographers need to face the challenge of how to represent this post Ansel Adams place we call home.

Many fresh approaches can be seen in a new traveling exhibition The Culture of Landscape. Here artists explore the dichotomies, myths, and symbols of our cultural and natural environment and like the original Dutch phrase, landschap, these artists make no distinction between humans and nature. The project mediates on how our construct of the landscape, from classic Edmund Burke and John Ruskin notions of the beautiful, the picturesque, and the sublime to the historic, psychological, and technological arrangement of commerce and industry, defines our civilization and shapes our identity.

The images concentrate on the marks of culture—consumption, labor, leisure, production, and semantics—as forces that transform nature. The project also examines the effects of cultural tourism by depicting the ways that people attempt to control and manipulate their environment. The subject is as much about human intervention as it is place, substantiating how people model their surroundings and how lives are affected by it. Their work shows how the landscape is a multi-layered human creation, revealing the complex interdependence between the natural world and the highly individualistic needs of its human occupants.

This informal group of artists is diversified in terms of approach, background, geography, and process. Their common bond is how they use photo-based images to demonstrate how human concerns and ideologies, from aesthetics to politics, reveal themselves in the making and interpretation of the landscape. Currently the group consists of Kim Abeles, Los Angeles, CA; Greg Erf, Portales, NM; Robert Hirsch, Buffalo, NY; Keith Johnson, Hamden, CT; James Nakagawa, Bloomington, IN; Ron Tarver, Philadelphia, PA; Brian Taylor, San Jose, CA; Maggie Taylor, Gainesville, FL; and Anna Ullrich; Seattle, WA.

The exhibition is scheduled to premiere at the New Bedford Art Museum, New Bedford, MA in 2004.