Stephen Berkman: Documentary Photographer of the Mind

…I am interested in photography’s first 40 years because it was at its zenith right from the start. Photography has not improved much; it’s just gotten more convenient. I like the visual code of the nineteenth century, the formality of it, the way things looked, and the mix between art and science.

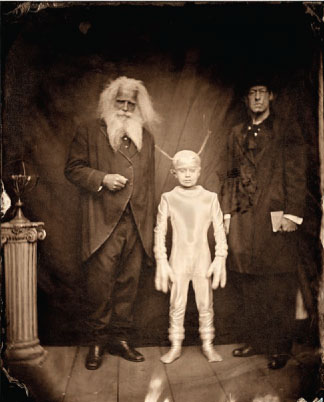

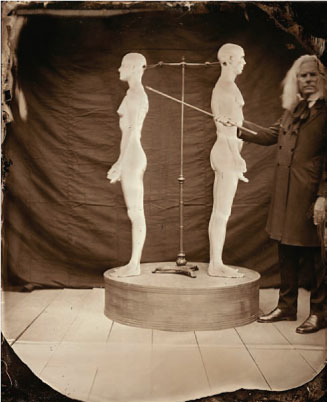

In an age when digital imagery often disrupts our expectations about photography’s traditional role as a witness to outer reality, Stephen Berkman does so using the collodion wet-plate process. Berkman’s enigmatic, time-traveling images demonstrate how an understanding of our world can be acquired through fabricated methods, thus revealing the multidimensional nature of photography and multiplicity of meanings and possibilities photographs can generate. The following are highlights from our recent conversations.

Robert Hirsch: Describe how you conceptually utilize history.

Stephen Berkman: I see history as being still malleable rather than being a closed circuit. Following this premise, what is being created is a nineteenth-century, visual panorama featuring a cavalcade of character types and their stations of life into which I insert or recover what has been lost to time.

RH: Do you admire any nineteenth-century photographers?

SB: My model is Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon). The scope of his work, the range of people he photo- graphed enthralls me. His staggering body of work led me to investigate the wet-collodion process. This discovery spurred me to begin my quixotic quest into nineteenth-century photography.

RH: What writers have influenced you?

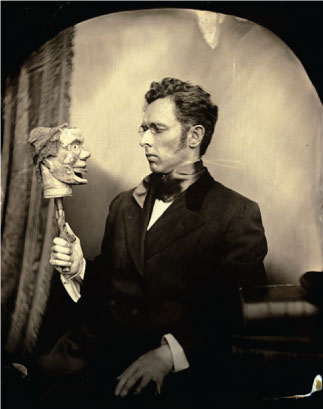

SB: Recently, I have been spending time with Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe, but prior to them, it was Jorge Luis Borges and Franz Kafka. I find perplexing things to be engaging, and that is what I strive for in my images too. Most photographs show you what is there, but I’m more interested in photographs that show you what is not there: things that are alluded to, ideas that can be reached only by following clues left behind. Sometimes, I feel like I’m creating a novel that is missing a few key chapters. I think there is merit in an elliptical narrative style. The seminal Beat writer William Burroughs thought the role of an artist is to dream for the public, although in his case it might be considered a nightmare for some.

RH: What other factors drive your work?

SB: I love anonymous nineteenth-century photography. Being an artist is like being in the import/export business. I am consuming everything all the time, both in terms of aesthetics and information, from books to films to music to road signs. All this subconsciouslygets mixed up and then exported back out. My ideas come unexpectedly while I am meandering through my life. They just seep-out at unexpected intervals, unannounced and unadorned. The French mime Marcel Marceau once said, “The solution is simple, but you have to find it first.” I always find myself going through blind alleys, cul-de sacs, and the wrong way on one-way roads to find my way through the work.

RH: Why are nineteenth-century processes essential to your work?

SB: The work acts as a coda to the nineteenth century. Time is paramount, as I am interested in time sweeps and time currents, the things that wash over our society; what is of interest, what is of value, and what changes. My desire is to create work that is both timely and as relevant to 1863 as possible. I make images that are simultaneously very specific and very vague, which allows the photographs to be fastened to reality yet open to possibilities.

RH: How do you envision and realize your work?

SB: Usually the idea and conception is almost instantaneous. Frequently it’s just a word, as I feel my work is often language driven. I tend to divide photographers into two camps. The first is writers who are photographers and the second is the photographers who are photographers. For example, Walker Evans’s work has the narrative element that communicates a story. A writer would have to expend many words describing what Evans photographed simply and concisely. On the other hand, Minor White’s images are about the visual space, the surfaces and textures that convey feelings. My work is heavily narrative in its construction, but I leave ellipses in the images to keep them engaging. I see myself as a documentary photographer, though in my case I’m documenting the interior of the mind.

RH: Describe your working studio.

SB: I photograph under natural north light, utilizing a large format view camera with a Dallmeyer lens from1864, whose glass is covered with nineteenth-century dust, which is probably why my photographs look the way they do. A typical exposure is between 30 and 40 seconds, without a posing stand, which introduces a slight amount of blur. The albumen prints complete the wet-collodion process.

RH: What role does concealment play in your work?

SB: I don’t consider it to be concealment; I just let viewers draw their own conclusions. However, the downside in a world full of upside is that my existence betrays the images.

RH: Why does the nineteenth century fascinate you?

SB: I am interested in photography’s first 40 years because it was at its zenith right from the start. Photography has not improved much; it’s just gotten more convenient. I like the visual code of the nineteenth century, the formality of it, the way things looked, and the mix between art and science. What intrigues me is getting inside the minds of people from another time and the feeling that their times, what we now consider the past, was at one time contemporary. The nineteenth century acts as both an anchor and a foil to my photographs.

RH: How does history affect your endeavors?

SB: We are the beneficiaries and victims of history. Think of different political actions that occurred over 100 years ago that we are still trying to overcome. We tend to look at the past as being preordained, but I don’t think that is the case. Making these pictures is how I examine this phenomenon. I find it fascinating how we got to where we are today.

RH: What do you want to achieve with your work?

SB: The writer Thomas Pynchon said, “You know what a miracle is? It is another world’s intrusion into this one.” I aspire to create work that transports one into a realm of the imagination, a real and direct experience. Each photograph acts like a portal into another world. I am fascinated with the idea that as soon as an image is taken that world almost immediately vanishes. The real value of a photograph is often not known until 40 or 50 years down the road. The more the world being depicted vanishes, the more interesting the photographs become because the resonance of time is added.

RH: Do you teach photography?

SB: I teach film at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA, where I also studied. Had I studied photography I would have been making films right now. My work has been described as single-frame films, in that they are highly cinematic images.

RH: What is important to consider when making images?

SB: One must have a unique and singular point of vision. This entails making work based on your own perspective and way of seeing that only you can do. Next, you need a field large enough to plow, a theme that is extensive enough to encompass your vision. Working with nineteenth-century photography provides me inexhaustible subject matter.

Editor’s Note: You can view more of Stephen Berkman’s images at stephenberkman.com.

![]()