Book Review

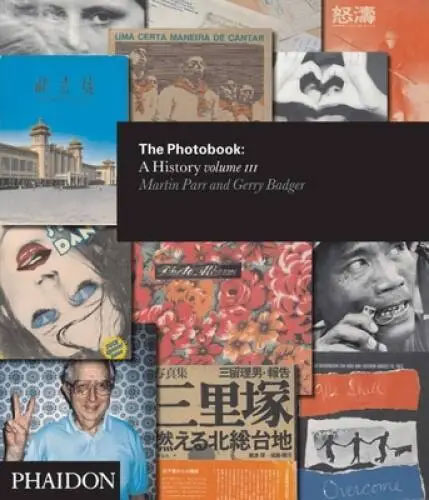

The Photobook: A History (Volume II)

Review by Robert Hirsch

From Afterimage 34.5

| Compiled by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, New York: Phaidon Press, 2006 |

The impetus for The Photobook: A History comes from Martin Parr’s intuitive understanding of the medium as a working photographer and his passion for collecting photo books. He utilizes his worldwide travels as a working photographer to unearth new books that most readers have never seen. Parr says, “I love the intimacy of the book and how it can open up and reveal itself. The whole idea of a book exploding into life is something I really like.”1 This outlook lead Parr to initiate a joint project with photo historian and critic Gerry Badger to “reorientate the importance of the photobook, which has not been given the importance that we think it deserves. I know that most of the information I get about other photographers comes in book form and I know how photographers get inspiration from looking at other books, and the great thing is that these things can travel between different territories very easily.”

Parr and Badger sought out books having “great photographs, a strong design sense, and something very definite to say” (they were not interested in retrospective books), placing the narrative account at the heart of their endeavor. For Badger, “the book is where photography sings its fullest and most complex song.” It is “in the book that a photographer can put pictures together with all sorts of things, especially text, and give them that kind of narrative value that the single photograph so often lacks.”

Volume II chronicles over 200 books using a thematic approach. Each book is represented by its cover and interior shots of its contents, conveying a sense that books are physical objects. Volume II opens with “The America Photobook” since the 1970s and features selections ranging from Les Krims’s self-published Making Chicken Soup (1972) to John Gossage’s The Pond (1985). The bulk of the book is largely devoted to expanding upon this canon that has dominated the field. Intriguing selections by Japanese and Dutch makers, re-enforced by Badger’s lucid writings, offset Parr’s collectors’ tendency for the “rare.” “The Company Book” chapter features ƒdouard-Denis Baldus’s commissioned and privately printed Chemins de fer de Paris ˆ Lyon et ˆ la MŽditerranŽe (Railways from Paris to Lyon and the Mediterranean, 1861–63) with tipped-in albumen prints. This is balanced with commonly printed United States high school yearbooks, which are likened to a corporate annual report. “The Picture Editor as Author” compellingly conveys the power of documentary photography to affect our thinking about essential issues with collections including War Against War (1924) by Ernst Friedrich, The Extermination of Polish Jewry: An Album of Pictures (1945), Century (1999) by Bruce Bernard, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (2000) edited by James Allen, and Here is New York (2002) edited by Alice Rose George, Gilles Peress, and Michael Shulan.

The digital age has taken us closer to realizing William Henry Fox Talbot’s dream of every person being his or her own publisher with a record number of books published last year. The affects of digital production are recognized with the inclusion of Alex Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), which first came into being via Soth’s inkjet printer, and Paul Fusco’s RFK Funeral Train (2001), which was first available as a print-on-demand book in 1999. Badger urges “young photographers to make limited edition books [both in physical and digital forms] to give the book a much clearer and deeper sense of your ideas.”

Lists always invite comparisons and their list would not be my list. “The Artist’s Photobook” section is disappointing, especially if you are experimentally inclined, intrigued by nonliteral depiction, or do not embrace what the authors call the Dsseldorf Tendency. Expressionistic bookmakers such as Syl Labrot, Joan Lyons, Sonia Sheridan, or Keith Smith are not covered. Not even Peter Beard, Arthur Tress, or Jerry Uelsmann are represented. However, if you favor a straightforward approach and believe as Parr and Badger do in Lincoln Kirstein’s observation that the business of photographers is to “catalog the facts of their epoch,” then you are likely to appreciate their selections; for this is why people make books—to present their views.

What separates this project from other such catalogs and “greatest hits” lists is Badger’s accessible writing. Badger forges historical links between the books, making a case for a history of the photo book as a global network of ideas and for its place in the history of photography. The biggest contribution Parr and Badger make is to fuel the act of looking, which precedes the act of picture making. Looking at images is a combination of consolation, distraction, torment, and ultimately inspiration. It is this love of looking at the world and wanting to hold onto it that makes one become a photographer.

NOTE 1. All quotes are from recent phone conversations with Martin Parr and Gerry Badger.

© Robert Hirsch