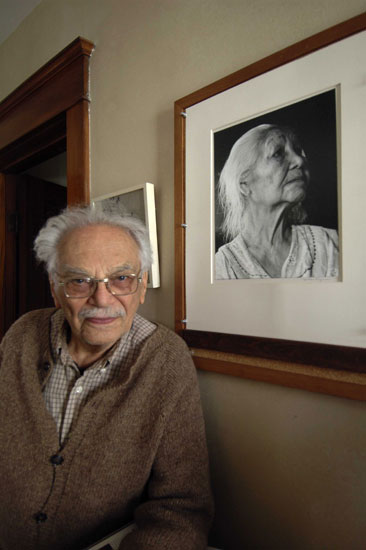

Milton Rogovin: Buffalo Troublemaker

From The Photo Review, March/April 2011, pages 19 -20.

Milton Rogovin (190–2011) was a first-generation American born to Jewish Ukrainian parents (Jacob and Dora) in New York City. He graduated from Columbia University’s optometry school in 1931 as the Great Depression unsettled the world and propelled him on a path towards political awareness. Rogovin first took on the responsibility of being a “Troublemaker” by challenging unfair working conditions and defending worker rights, which led him to organize the Optical Workers Union in New York City. In 1938 he came to work in Buffalo, NY, but after picketing his boss’s offices for unfair labor practices, he was fired. With union backing, he opened his own practice the following year and continued his political activities until he entered military service during World War II when he also acquired his first camera.

As the librarian of Buffalo’s communist party, Rogovin was subpoenaed in 1957 and ordered to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) where he refused to name names. The next day The Buffalo Evening News headline proclaimed: “Rogovin Named as Top Red in Buffalo.” The fallout was immediate and devastating. His children were shunned and his optometry business dropped by 50 percent. Fortunately, Milton’s wife, Anne Setters, a special education teacher, resolutely stepped into this breach. She encouraged and supported Milton, allowing him to concentrate on his photography, which he did with mentoring from Minor White. Responding to an invitation from his friend, Professor William Tallmadge of Buffalo State College, Rogovin began his first significant body of work Storefront Churches — Buffalo (1961). This led to numerous other projects from street corners of Buffalo’s West Side and the Lackawanna, NY steel mills, to fields in Chile, and coal mines in Appalachia, China, Cuba, Mexico, Spain, Zimbabwe and elsewhere.

Rogovin operated within the parameters of social documentary practice that can be traced back to John Thomson, Jacob Riis, and Lewis Hine, utilizing photography in the service of social reform. He also admired the photographs of Margaret Bourke- White and the Farm Security Administration group, especially Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, plus the work of his friend Paul Strand. Utilizing a twin-lens Rollieflex camera, Rogovin’s direct approach was relaxed and unpretentious: people posed themselves within their environment. Working as a team with his wife Anne, a driving, behind-the-scenes force, 18 Rogovin only asked his subjects to look at the camera, rarely making more than three exposures. He processed and printed his black-and-white materials in a simple basement darkroom and gave prints to his subjects. His vision rationally chronicles, rather than subjectively imagining, concretely representing rather than transforming his subjects. Although his photographs are implicitly political, he did not engage in mythmaking, rather he openly showed people in relation to their social and working conditions.

In the early 1970s, Rogovin began a series of portraits that featured working-class people who lived near his downtown Buffalo optical business. At the suggestion of Anne, he returned to rephotograph the same people in the early 1980s and again in the 1990s. The resulting photographs were published as Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited (1994). This condensed time capsule, with its underlying pathos of loss, allows one to witness how these people changed and endured over time.

Milton told me, “I wanted to make sympathetic portraits of the poorest of the poor in our community that showed them as decent human struggling to get by. Most are considered los olvidados,1 the forgotten ones, who are without a voice or power. Most people don’t even know these people exist. By photographing them I bring to the attention of the general public that they are people just like us and should not be looked down upon or abused in any way. It was the poor people who interested me and I wanted to photograph. I was never interested in photographing the rich.”

This kind of historical “forgetfulness” is socially dangerous, allowing us to ignore or trivialize the historical plight of those beyond our purview. Rogovin thought it was absolutely necessary to act in the here and now to remedy problems that confront us; thus his photographs look reality straight in the eye to arouse one’s empathy and social conscience. This echoes Elie Wiesel statement, “The opposite of history is not myth. The opposite of history is forgetfulness.”2

Commenting on the death of his father, Mark Rogovin informed me, “It is rewarding to have the mainline press and individuals from around the world send their condolences. This is what my parents referred to as ‘Harvest Time,’ a gathering and recognition of their combined works.”3 In addition to having the photographs seen in galleries and museums, his family wanted to have their efforts utilized in classrooms. For this purpose they’ve constructed a website, www.MiltonRogovin.com, which has a section devoted to educators in both English and Spanish.

Rogovin’s photographs have been internationally admired, collected, and exhibited; they are in museum collections nationwide including the Creative Center for Photography, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Library of Congress, and the Burchfield-Penney Art Center. Even so, Milton continued to find beauty in everyday living, such as having mural-size photographs of steel workers installed in Buffalo subway stations, holding a book signing at Wegmans food market, and regularly attending Buffalo anti-war demonstrations. As Rogovin lived to be an elderly man, many people thought of him as a kindly grandfather figure. However, this was not the case. Milton Rogovin remained a feisty troublemaker with a fine sense of humor. Milton ultimately got the last laugh, not only outliving his enemies, but also living long enough to see his work recognized by The Man who once tried to silence him.

- This phrase came from Luis Bunuel’s Los Olvidados (The Forgotten Ones), a 1950 social realistic/surrealistic film.

- Wiesel, Elie. “Myth and History,” in Myth, Symbol, and Reality, Alan M. Olson ed. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1980), p. 30.

- Telephone conversation between Mark Rogovin and the author, February 7, 2011.

Robert Hirsch, © 2011

Robert Hirsch is the Focal Press Sponsored Speaker at the National Society for Photographic Education Conference in Atlanta, GA on Thursday, March 10, 2011 at 1:30 PM. His presentation will cover his latest book Exploring Color Photography: From Film to Pixels, Fifth Edition and his latest installation The 1960s Cubed: A Visual History, which will open this spring at both CEPA and Indigo Galleries in Buffalo, NY.

For more information visit: www.lightresearch.net. Additional Information: Herzog, Melanie Anne. Milton Rogovin: The Making of a Social Documentary Photographer, (Seattle, WA: Center of Creative Photography in association with University of Washington Press, 2006).

For a full-length interview see, “Milton Rogovin: Activist Photographer,” see:

Interviews Rogovin Afterimage