John Pfahl, The Garden as Landscape

This interview is based on discussions between John Pfahl and myself regarding the publication of his latest book, Extreme Horticulture, by Frances Lincoln, Ltd. and distributed in the U.S. by Antique Collectors’ Club (hardcover, $50.00, 144 pages, ISBN 0-7112-2012-3) with an introduction by Rebecca Solnit.

Robert Hirsch: What were your motives for doing Extreme Horticulture?

John Pfahl: When I was a boy I was given a small part of my mother’ s backyard garden to fool around with and I started performing weird experiments on plants. For instance, I would inject food dye into green tomatoes in hopes that they would turn blue when they ripened. I seem to always have had this “control over nature” gene. I have a small garden here in Buffalo, New York, and am still experimenting with different plant schemes. Through frequent visits to Britain, I became fascinated with the classic English gardens. The British display such eccentricity in their gardens. They tend to let things go and take their own form and then they celebrate it. This fits in with my general program of dealing with the relationship between humans and their landscapes, so I started to look at gardens closer to home to see what I could photographically do with them.

RH: How are your garden photographs different from conventional garden photographs?

JP: I really like gardening magazine photographs and initially found it difficult to do something different. Most garden photographers tend to be formulaic. They either focus on the individual plants, throwing the background out of focus, or present an overall view where the garden becomes a field of textures. I wound up using the same approach I had used for my Waterfall series, where the almost panoramic 6×12-cm. negative format provided a generous context for the subject. Here I used a Horseman FA 4×5-inch field camera on a tripod, generally with a wide-angle lens. It was very important for me to have everything in the picture in focus.

RH: How would you characterize your ideas about depth of field, image focus, and sharpness?

JP: Perceptually, when one walks through a garden, one looks at specific plants sequentially while everything else becomes a blur. However, having everything from foreground to infinity in focus creates a surreal dream-like image where everything is equally seductive and inspectable in minute detail. This approach can be a hard sell in a time when many photographers are making fuzzy images.

RH: It does go against the trend of exploring notions of focus. Maybe you could get a stamp, “John Pfahl: Everything has always been in focus.”

JP: That’ s a great idea! Even when you look at my Niagara Sublime pictures, they are all in focus and are only blurry because of the motion. My theory is that people are still wary of calling photography an art. Blurring photography’ s descriptive properties makes it easier for people to categorize it as an art form.

RH: How long did you work on the garden project?

JP: Four years: from 1998 to 2002. I started by doing experiments in the formal garden at George Eastman House. I got very close to the plants, shooting from ground level with a wide-angle lens and maintained a great depth of field. These early trials did not pan out, but they proved to be important in pointing out what I was really interested in: the unusual, the bizarre, the abundant, and the exuberant.

RH: How is digital imaging affecting your photographic approach?

JP: I don’ t have a digital camera, but several aspects of my book production depended on digital files. For example, when I laid out the book, I printed a quarter-size version on my Epson printer to help me with the sequencing. The original 10 x 20 inch prints were drum scanned in Buffalo and high-quality repro proofs were sent, along with the files, to the printer in Hong Kong.

RH: Will you continue to shoot film and scan it?

JP: Yes, my large negatives contain a tremendous amount of information and are easy to work with, but I’ m thinking that this is maybe the last project I do where the end result is a chemical print.

RH: Have any of the garden images been digitally altered?

JP: I used corrective measures on one image to get rid of a few fence posts.

RH: What are a few of your favorite images from this project?

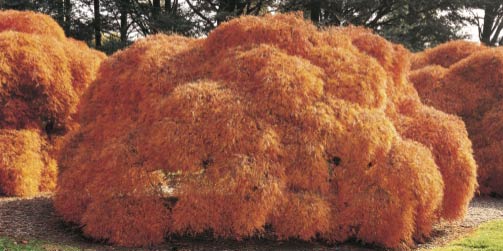

JP: Crazy images like Threadleaf Japanese Maples at Hershey Gardens. It’ s not something you see everyday and the form has a strange anthropomorphic quality. Many people think of it as a cartoon character, like the “Blob.” Another favorite, for much the same reasons, is Relaxed Euphorbia at Lotusland, an extraordinary garden in Montecito, California. And, of course, I am always partial to topiary such as Yew Hunt Scene and Begonia Fish.

RH: How did Rebecca Solnit, who recently published River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West (2003), come to write the introduction?

JP: I found her book, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2000), to be beautifully written and I liked the way she didn’ t just write about the subject at hand, but went off on wild tangents about history, politics, science, the environment, and miscellaneous topics. She told me that she wasn’ t going to write specifically about my pictures or about my past work.

RH: Why did that appeal to you since most people want an essayist to write about their work?

JP: I have already had a lot written about my work and this book is not really about me as an artist. It’ s a subject driven book and I felt that the essay should concentrate on the subject. This created the dilemma of how to illustrate her essay. We decided to use old photographic postcards. I especially liked using “exaggeration” postcards, those with gigantic apples, cabbages, and pumpkins in this context. They work well with the title of her essay, ÒThe Botanical Circus: Adventures in American Gardening.” The design of the book also emphasized subject over photographer. Unlike the typical artist’ s monograph, where reproductions might be one to a page and framed in lots of unbroken white space, in this book there are a variety of formats, including large pictures that spread over two pages and bleed off the edges. I love the way this makes the photographs seem to expand. We also included a plant index and little snapshots that were taken in the same gardens as the view camera images. And then there were the captions.

RH: What was caption process like for you?

JP: Totally new. It was difficult and exhilarating, but thanks to the Internet I loved doing the research. The hurdle was to encapsulate the story of the plants, the people, and the gardens into sixty words or less. It was like writing seventy little haikus.

RH: Did you learn anything unexpected from your research?

JP: Doing the research opened my eyes to how limited and superficial the practice of photography can be. By concentrating only on the visual, photographers often do not have a clue as to other aspects of the story. This is certainly true of my own past work, and, I suspect, of much of today’ s photography. I did a lot of research about the plants and their growing habits, the people who designed these gardens, the gardens themselves, and the people who paid the bills to create them. I learned that extremely wealthy people, the Bill Gateses of the day, formed many of these big U.S. gardens in the 1910s and 1920s as a way to display wealth and taste. They were often based on European prototypes, mostly English. Many of these gardens, such as Huntington Gardens, the Elms in Newport, and Longwood Gardens, were appendages of splendid mansions.

RH: What do gardens express about our relationship to nature and why do you think they have such widespread appeal?

JP: The thing I love about gardens is that no matter how hard you may try to impose your will on plants, the plants will have their own way in the end. It’ s not a battle, but more of a tussle between gardener and the garden. A garden is never final. It is always evolving. There are ever shifting things that one thinks one can control but can’t. Maybe photography is that way too, one thinks one gains control over the world when one makes a photograph, but when you get back to the darkroom you realize that you have something completely different from what you originally thought you had.

RH: How would you compare this book to your earlier Altered Landscapes?

JP: It may not be far-fetched to think that by placing grids and strings onto landscapes that I was actually practicing a form of gardening. Imposing my will on nature, just momentarily, organized the scene. It would not have looked as ordered without my little additives. It was a way of gardening.

RH: What about the future of landscape photography?

JP: I think it is more important now than it ever had been. When nature is threatened by so much human activity it is imperative that it be brought to people’ s attention so that they know what is happening. And yet, fewer people seem to be interested in doing that today.

RH: Why do you think that is?

JP: In the past, many photographers deemed the subject more important than themselves. Now that photography is an art form the activity is much more self-conscious and the artist winds up being more important than the subject. Then again, the function of showing the world has been largely taken over by documentary film and video, both mediums that can provide a broader context for understanding than still photographs. That said, one fantastic photograph can still speak so succinctly and directly that viewers can carry the image with them in their minds forever and that can change their thinking. For example, regardless of what you think about Sebastião Salgado’ s approach, his amazing Brazilian gold mine photographs imprint themselves on anyone that sees them.

RH: What qualities make one a good photographer?

JP: The ability to be completely concentrated on what you are doing when you are doing it, both when making the exposure and when printing your photographs. One needs to pay passionate attention to everything in the picture.

RH: What times of day and what types of light you prefer to make photographs?

JP: There are three times of day when I photograph, the early morning, noon, and the late afternoon, because the landscape seems more articulated at those times. I generally find it difficult to photograph on both cloudy and cloud-free days. I love the phrase that Kodak used to print with their film instructions: Òhazy bright.” That’ s the type of light I like.

RH: In terms of how your photographs are put together, there seem to be some people who think good phoand excitement. It’ s everything you could possibly want.

JP: I obviously think that good photographs are found, not made. The joy is in the hunt. I thrive on engagement with the outside world. It is constantly surprising, amazing and nourishing. However, this is not to disparage the crafting of a photograph. One needs a combination of skill, control, and readiness to make a good photograph. The longer you work the more automatic it becomes. Luck plays a big part in the hunt for pictures. You have to be there at the right moment, but only experience can tell you when the right moment may be about to occur. I returned to many of these gardens several times. For example, in Hornbeam Vista, Niagara Parks Botanical Garden, I wanted the sun to come straight down the middle of the allée. It took numerous trips, at different hours, to get those leaves to shimmer with light and color in my photograph.

RH: You can’ t just push a button.

JP: There are intense periods of hard work, when the light is changing or it threatens to rain, but there are also long periods of just plain waiting and watching. It’ s a mixture of boredom excitement. It’ s everything you could possibly want.

John Pfahl Monographs

Extreme Horticulture, essay by Rebecca Solnit (London: Frances Lincoln, Ltd., 2003), $50 hb. Also published in Germany as Das andere Eden by Gerstenberg Verlag.

Waterfall, essay by Deborah Tall,(Tucson, AZ: Nazraeli Press, 2000).

Permutations on the Picturesque, essay by Gary Hesse (Syracuse, NY: Lightwork, 1997).

A Distanced Land: Photographs of John Pfahl, essay by Estelle Jussim, with series introduction by Cheryl Brutvan (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press in association with the Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, 1990).

Arcadia Revisited: Niagara River and Falls from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, essay by Estelle Jussim and Anthony Bannon (Albuquerque: University ofNew Mexico Press and the Buscaglia- Castellani Art Gallery of Niagara University, 1988).

Picture Windows, introduction by Edward Bryant (Boston: New York Graphic Society; Little, Brown Company, 1987).

Altered Landscapes: The Photographs of John Pfahl, introduction by Peter Bunnell (Carmel: The Friends of Photography in association with the Robert Freidus Gallery, 1981).

![]()