Transformational Imagemaking

Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960

About the Book

Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 is a groundbreaking survey of significant work and ideas by imagemakers who have pushed beyond the boundaries of photography as a window on our material world. These artists represent a diverse group of curious experimentalists who have propelled the medium’s evolution by visualizing their subject matter as it originates from their mind’s eye. Many favor the historical techniques commonly known as alternative photographic processes, but all these makers demonstrate that the real alternative is found in their mental approach and not in their use of physical methods.

Table of Contents

TRANSFORMATIONAL IMAGEMAKING

Fingerprints

A Concise Historic Overview

Realer Than Real

The 1960s Zeitgeist

The Haptic Personality

An American Hybrid of New Realism

WEST COAST ROOTS

GROUNDBREAKING EXHIBITIONS

EAST COAST MAKERS

PROGRESSION

EVOLUTION

INFERENCES

REVIEW

Every once in a while a book is published that promotes a shift in the substance of a discipline.

Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960

Robert Hirsch. Focal Press, New York and London, 2014. 242 pages, with 241 colour illustrations. Softcover £30.99/$53.95, ISBN 978-0-415-81026-5.

Every once in a while a book is published that promotes a shift in the substance of a

discipline. Photographer, curator, and photo-historian Robert Hirsch’s Transformational

Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 is such a book. It begs the question of

the subject and substance of the history of photography and yields a new look at a medium

that is more diverse and flexible, and more refreshingly original than is usually credited. Of

course, pushback against the discipline’s roots in Beaumont Newhall’s and John

Szarkowski’s fetishisation of so-called ‘pure’ or ‘straight’ photography is not new.

However, Hirsch’s book reveals that it was not only photo-historians but also a diverse

group of US artists who have been responding directly to the simplistic, photography-aswindow

approach since Newhall’s The History of Photography: From 1893 to the Present was

first published in 1937. At the same time, in a substantial preface, an introductory scholarly

essay, and over fifty artists’ interviews, this beautifully illustrated volume uncovers traditions

of what are commonly called alternative photographic practices – the ‘transformational

imagemaking’ of Hirsch’s title – as having been central to photography from its very start.

Above all else, this book presents a strand of photography-based art that has too often flown

under the radar of scholars of photographic history, and it delivers an astonishing array of

recent work that harnesses photography’s perceived indexicality to play with received ideas

about perception and reality. In so doing, the book allows for a reconsideration of all

photographs as products of artistic imagination created by ‘makers’ rather than ‘takers’, in

Hirsch’s words.

This book begins with an epigraph from Robert Heinecken that challenges the foundational

and persistent myth of photography: ‘We constantly tend to misuse or misunderstand

the term reality in relation to photographs. The photograph itself is the only thing that is

real’. Hirsch’s preface lays out the objections to handmade photography that have kept it

from being substantively engaged in photographic histories: that it is not analytical or

rigorous enough; that it is fake; or that its embrace of beauty or demonstrations of technical

expertise detract from photography’s real strength, its objectivity. Hirsch reveals all of these

as red herrings since all photographs are mediated in some manner or other. Further, he

points out that the creative flowering of visual experimentation that we see as the heart and

substance of today’s digital photography can be traced back to these ‘outlaw methodologies’

of 1960s and 1970s counterculture.

While this alternative photographic history focuses on the past fifty years, Hirsch begins

the main essay of the book, ‘Transformational Imagemaking’, much earlier, with the

stencilled outlines of hands made more than forty thousand years ago on a cave wall in

Spain. These ancient images evoke what Hirsch sees as the twin aspects behind the making

of photographs, the desire to leave a direct trace – here the outline of actual human hands –

and the fact that this direct trace is always mediated by the artist’s creative process. When he

turns to the origins of photography, Hirsch points out that all early forms of the medium

shared one fundamental limitation that would immediately lead to their being altered by

hand: they lacked colour. Hirsch surveys a number of other historical traditions of altering

photographs: these include combination prints, in which, paradoxically, photographs were

altered in order to create more accurate views; pictorialism, the first serious art-photography

movement; and the varied experiments of members of the early twentieth-century European

avant-garde. These examples demonstrate the range of valences that handmade photography

had already acquired when it re-emerged with a vengeance in the 1960s. This resurgence of

photographic alternatives paralleled the rise of other countercultures, and led to the creation

of new, artist-run organisations to support and cultivate photography such as the Friends of

Photography in Carmel, California or the CEPA Gallery in Buffalo, New York. Another

reason why the story told by Transformational Imagemaking is a new one is that, as Hirsch

points out, while some of these artists appeared at shows held in the Museum of Modern

Art, New York and other large museums, the many exhibitions and programmes organised

by these new alternative organisations were usually not well funded, so few catalogues were

published to disseminate the ideas of this movement.

Transformational Imagemaking privileges a maker’s perspective, which is a real strength

since Hirsch himself is an experimental photographer besides curating and writing on the

subject of photographic history. The bulk of the book is made up of fifty-one chapters on

specific artists. Each has an overview essay, an interview that Hirsch conducted with the

artist or someone close to him or her, and colour reproductions. These chapters are

organised into six sections that trace the origin and progression of handmade work through

space and time. The first of these sections, ‘West Coast Roots’, begins with the most

influential figure of this volume, Robert Heinecken, whose turn to the found images of

media culture challenged dominant modes of photography and made him, as Hirsch

suggests, a Dadaist for the 1960s generation. ‘Groundbreaking Exhibitions’, the second

section, briefly examines two key curators, Nathan Lyons and Peter Bunnell, who showed

this work in minor and major exhibition spaces and helped to foster a movement. In the

face of a culture that was increasingly automated, the homemade approaches taken by many

centred in the northeast is the focus of ‘East Coast Makers’, which includes some wellknown

photographers such as Jerry Uelsmann and Duane Michals. The artists in this section

also introduce significant new content to the book – namely how alternative photographic

processes provided a platform to visualise other challenges to the status quo. Women artists

and artists of diverse backgrounds such as Betty Hahn, Clarissa Sligh, Tatana Kellner, Bea

Nettles, Catherine Jansen, and Stephen Marc dominate this section and reveal how photographic

media enabled them to tell new kinds of stories and reveal perspectives from outside

the mainstream. The rise of gay liberation and the AIDS crisis was central to the development

of a number of these photographers’ work, as is revealed in interviews with

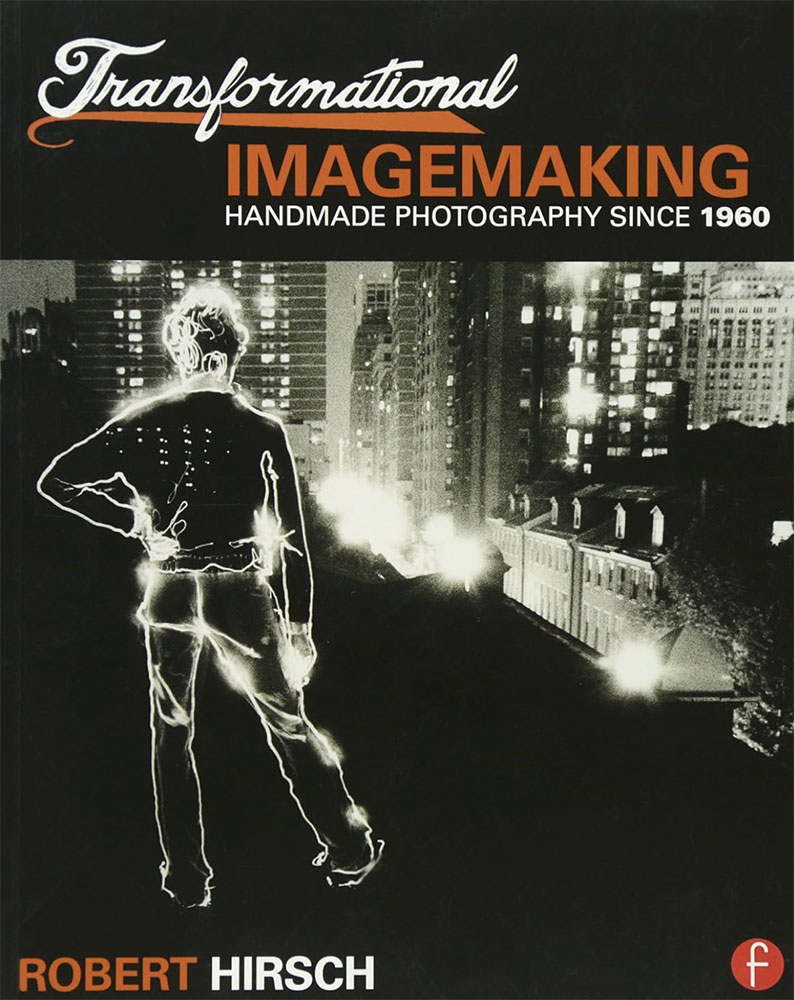

Duane Michals, Robert Flynt, and David Lebe. Lebe recounts how he traced neon-like

outlines of urban cowboys with a flashlight and captured them on film to visualise sexual

attraction. For him they served as ‘a neon advertisement announcing the thrill of my

existence as a gay man – and of all gay men’. On the cover of Transformational

Imagemaking this same image also doubles as an emblem for Hirsch’s assertion that the

direct capturing of light on a photographic surface was a means for artists to reflect both

their exterior and interior worlds in a rapidly modernising culture.

Subsequent sections of the book, ‘Progression’ and ‘Evolution’, focus on the continued

spread of these transformational imagemaking techniques and take us up to the present time

with beautiful and often eerie works by artists such as Ted Orland, Maggie Taylor, Vik

Muniz, and Dinh Q. Leˆ. In ‘Inferences’, the final essay in the book, Hirsch explores the ways

in which the triumph of the digital has led to a greater acceptance of manipulated photography

and also, in some quarters, a return to the analogue and the handmade as a means to

rediscover chance and uniqueness in a world where computers have often smoothed away

any form of visual surprise.

Throughout the interviews in the book, Hirsch’s pithy questions provoke rich

responses from each of the artists or, in cases where they have passed away, those who

know their work best. Joel-Peter Witkin, whose photographs have always struck this

reviewer as rather carnivalesque, comes across as surprisingly spiritual when he talks

about the importance of Catholicism in his life and states unapologetically: ‘I want to create

work that changes people’s lives’. Of Human Nature, Martha Madigan’s deceptively simple

life-sized solar photographs of human bodies from newborns to centenarians, she says:

the sun is a metaphor for the way I work, inextricably bound to the source of life, and

as a direct experience of the light shining through all of the senses of the body. I create

solar images because my work moves between art practice and spiritual practice. It is a

transformational way to understand the essence and purpose of human experience.

Here photography is both scientific and otherworldly all at once, as it directly traces bodies

that will change and pass away before these images do.

Given its wide-reaching implications as well as its rich specificity on the most significant

alternative photography-based artists working in the USA during the last halfcentury,

Transformational Imagemaking is essential for library collections and should

become standard reading in the teaching of history of photography. Our understanding of

this medium is likely to become a lot freer and richer because of it.

Elizabeth Otto

© 2015, Elizabeth Otto

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2015.1035535

![]()