Book Review

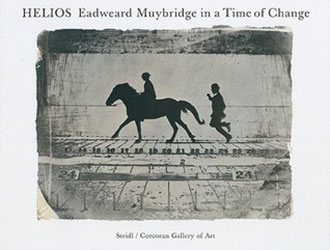

Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change

Review by Robert Hirsch

| Text by Philip Brookman, Rebecca Solnit, Marta Braun, and Corey Keller (London: Steidl, with Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2010) |

Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change places Muybridge’s artistic and technical accomplishments within the context of late-nineteenthcentury American and European history. This lavishly illustrated catalog, with excellent production values, accompanies a retrospective exhibition of the same name that was organized by the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s chief curator Philip Brookman. The publication features wide-ranging, first-rate essays by Brookman, Marta Braun, Corey Keller, and Rebecca Solnit that investigate and interpret Muybridge’s western landscape work and his encyclopedic drive to catalog locomotion.

Through words and images, the book maps how Muybridge, who was originally a publisher and bookseller, established a reputation at the close of the 1860s as a multitalented and resourceful maker of photographic views of the American West, including Yosemite Valley, San Francisco, and Alaska, under the moniker of Helios (the sun in Greek mythology) in which he utilized pre- and post-exposure methods to generate dramatic artistic effects including clouds and moonlight.* Foreshadowing his later involvement in finding new methods of representing photographic time, he also made long, ghostly exposures of waterfalls that depict more time than the human eye can process, thus offering a visual representation on the theme of variability over time. Today, Muybridge is best known for his massive atlas of stop-action motion studies, Animal Locomotion, first published in 1887.

The current catalogue text recaps the familiar story about how these studies began in 1872, when railroad tycoon Leland Stanford commissioned Muybridge to photograph his horse, Occident, to determine whether it ever lifted all four hooves off the ground at once. His The Horse in Motion sequences, which mechanically describe and discreetly dissect action too quick for the eye to decipher, offered proof that this was indeed the case. In turn, this opened the gates of perception to his recording of motion in humans, birds, and elephants that changed the way people perceived the world and provided a catalyst for the development of motion pictures.

We also learn that long before Photoshop, one of the most influential photographers of the nineteenth cen47 tury elaborately hand-constructed the images that came to be accepted as authorities of veracity. Muybridge wanted to formulate a visual dictionary of human and animal locomotion for artists. As a technically minded artist, Muybridge was concerned with how subjects in motion looked. He took single images and arranged (collaged) them to form an assemblage that was rephotographed and printed to produce the illusion of movement. His sequencing techniques used persistence of vision to encourage the belief that the action was continuous when it was not. Muybridge chose artistic pictorial effect over a scientifically accurate and complete recording of movement, and to that end even altered the numbering system of his negatives to construct a sequence whose individual elements came from different sessions. Taking fragments and individual images, he built elaborate narrative sequences in which tiny stories unfolded.

While his constructions may not be verifiably scientific for the analysis of locomotion, Muybridge’s protocinematic montages impacted artists, such as Thomas Eakins, who were interested in redefining the vocabulary of locomotion that lay beyond the visual threshold. His introduction of a gridded and numbered background allowed the space and time the subject traveled to be scientifically and visually defined and measured. The grid calibrated and quantified the visual data and mimicked the complete presentation sequence of each subject.

This book also points out how Muybridge’s work can provide a window into gender roles of those times. In his staged photographs men perform bricklaying and carpentry while women do the sweeping and washing. Under a pseudoscientific guise, Muybridge made visible what was hidden by social convention — a masculine, voyeuristic, erotic fantasy. Muybridge produced more plates of nude women than of any other subject, covering a variety of sexual proclivities. His small action sequences of women kissing, taking each other’s clothes off, pouring water down each other’s throats, and smoking in the nude as well as his naked men pole vaulting, wrestling, throwing a discus, and batting a baseball invite viewers to vicariously join in this provocative handiwork.

A close examination of the book’s illustrations reveals how Muybridge used the authority of the camera to convince viewers that what they were seeing was accurate, even if it did not conform to anything they had previously seen. Each camera image enclosed a slice of time and space in which formerly invisible aspects of motion were contained. This new reality disturbed the thinking of artists who relied on “being true to nature” as their guiding force. It was clear that what was accurate could not always be seen and that what could be seen was not always factual. By showing us what was once invisible, Muybridge established that much of life is beyond our conscious awareness — what Walter Benjamin later called optical unconsciousness — and that much that had been accepted as artistic truth was just another word for conformity.

In due course of the text, readers can learn how Muybridge’s typological archive presents physical bodies as kinesthetic machines within a gridded frame of passing time and space, which generated a proto-cinematic interplay between fixed and fluid moments. His abundantly coded building blocks of the previously invisible expressed a new way of seeing the physical attributes of time and motion by compositing the real with the imagined via photomechanical means. Along with Étienne-Jules Marey’s continuous, overlapping images of locomotion, Muybridge’s vast quantities of pictures (in this case numbers did matter) became flowing catalysts for the cubists and the futurists in their quest to represent modern conceptions of the interchange of bodily action and time, upending models of stability and stasis that had informed centuries of artistic practice.

Today we can see the continued aftereffects of Muybridge’s pictures in DSLR cameras with 1080p video capture that could become a game-changer in how we make still photographs. As the technology advances, imagemakers could be recording high-quality, moving sequences of “indecisive moments” from which they would later pick out the decisive moment(s), which would also be subject to future revision.

Ultimately Muybridge’s constructed still sequences, which simultaneously synthesized life forms and machines, remain revolutionary and affect photographic practice because they continue to make us stop, look, and reconsider a dangerous human attribute of believing in something that ain’t so.

Also recommended: River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West by Rebecca Solnit, Gallop: A Scanimation Picture Book by Rufus Butler Seder, plus the website www.eadweardmuybridge.co.uk.

NOTES *In what could be a significant backstory, Weston Naef speculates whether or not Muybridge had the expertise to make these images and could other photographers, particularly Carleton Watkins, have made the photographs that Muybridge published under Helios. See Tyler Green’s Modern Art Notes at http://blogs.artinfo.com/modernartnotes/2010/06/only-on-man-the-newest-eadweardmuybridge-mystery.

© Robert Hirsch