Why People Make Photographs

We often assume that all pictures are “signs” that stand for something and possess an innate semiotic (pertaining to signs) structure and value. But is it also possible that pictures are just pictures that represent circumstances that cannot be expressed in any other way. Pictures possess their own native structure that may defy explanation regardless of how many words are wrapped around them. Most people who make photographs share the common bond of wanting to represent (commemorate) a likeness of something that is important in their life. Individuals make photographs because words often fail to adequately describe and express their relationship to the world. Pictures are an essential component of how humans observe, communicate, celebrate, and remember. For the majority of people the standard, automatic type of photographic record keeping is adequate, but for others it is not. This smaller group finds it a necessity to control, interact, and manipulate the photographic process and to interpret and actively interject their responses to the subject.

A photograph is not necessarily about something; rather it is something in and of itself. A photograph may be enigmatic or it may allow a viewer access to something remarkable that could not be perceived or understood in any other way. It is analogous to what the dancer Isadora Duncan said: “If I could explain to you what I meant there would be no reason to dance.”

Being involved in photography as an educator, curator, gallery director, and author, I have observed a reoccurring core group of questions that people ask regarding the imagemaking process. A thoughtful discussion surrounding issues of why people make photographs allows photographers to understand how the concepts and processes of photography have evolved and in turn place themselves in a more informed position to explore future possibilities. This column is the first in a planned series of columns of thirty questions and answers that are designed to encourage photographers to gain a larger overview of fundamental concepts, images, and issues that can inform their work. By thinking through this series, photographers can expand and deepen their vision and interests rather than following a current style or trend. The responses do not preclude other answers. They offer an initial pathway to form the basis of a discussion, to provoke, and in turn to help people formulate their own solutions. I encourage readers to respond to this initial column with their thoughts and questions to create an interactive dialogue around these issues.

1. Who is a photographer?

A photographer is a person who has decided to become and pursue the life of a photographer.

2. How does one become a photographer?

Looking at photographs can be a primary activity. Photographs are made from other photographs, as well as drawings, paintings, and prints. Look at what drives your curiosity. Look at the classics. They have been preserved because the patterns recorded in them have proved to be invariably useful over time. Look at contemporary work that is wrestling with new and different ways of expressing ideas. Read, study, and practice different methods of photography, not for the sake of technique, but to discover the means to articulate your ideas. Step back from the familiar to better understand it. One big peril facing photographers is lack of commitment that translates into indifference in their work. Talking, thinking, and writing about photography are vital components of understanding the process, but these activities do not make one a photographer. Ultimately, to be a photographer one must fully engage in the process and make photographs (usually lots of them).

3. What does a photographer do?

A photographer contemplates the nature of making photographs, the cerebral and emotional drive of working with a subject and process. Once this is accomplished the photographer can then act to provide a physical form in which time is manipulated and/or suspended to allow a subject to be thoughtfully examined.

4. Why is photography important to us as individuals and collectively as a society?

In 1999 a National Public Radio reporter asked Oklahoma tornado survivors what their most irreplaceable object was. One after another said that their snapshots were what they wanted to recover from their ruined homes as their other material possessions could be eventually replaced. This reveals the crux of why people photograph: to save and commemorate a subject of personal importance. The image may be a memory jog or an attempt to stop the ravages of nature and time. Regardless of motive, this act of commemoration and remembrance is the critical essence of both amateur and professional photographic practice.

What does this mean in terms of artistic practice at the beginning of a new century? There are more options than ever to pursue. Whether the images are found in the natural world, in a book, or on a screen, part of an imagemakers job is to be actively engaged in condition of “looking for something” How this act of looking at a subject is organized, its particular routines, uncertainties, astonishments, and quixotic complexities, are what make each photographer unique.

5. Why is it important to find an audience for your work?

Part of a serious photographersí job is to engage and stimulate thinking within the community of artists and their world at-large. Without an audience to open a dialogue the images remain incomplete and the artist unsatisfied.

6. What can images do that language can not do?

An accomplished photograph can communicate visual experiences that remain adamantly defiant to words. The French writer Albert Camus stated: “If we understood the enigmas of life there would be no need for art.” We know that words have the power to name the unnamable, but words also hold within them the disclosure of a consciousness beyond language. Photographs may also convey the sensation and emotional weight of the subject without being bound by its physical content. By controlling time and space photo-based images allow viewers to examine that which attracts us often for indescribable reasons. They may remind us how the quickly glimpsed, the half-remembered, and the partially understood images of our culture can tap into our memory and emotions and become part of a personal psychic landscape that makes up an integral component of identity and social order.

7. What makes a photograph interesting?

A significant ingredient that makes a photograph interesting is empathy for it gives viewers an initial path for cognitive and emotional comprehension of the subject. Yet the value of a photograph is not limited to its depiiction of people, places, things, and feelings akin to those in our life. An engaging image contains within it the capacity to sensitize and stimulate our latent exploratory senses. Such a photograph asserts ideas and perceptions that we recognize as our own but could not have given concrete form to without having first seen that image.

8. How is meaning of a photograph determined?

Meaning is not intrinsic. Meaning is established through a fluid cogitative and emotional relationship among the maker, the ppphotograph, and the viewer. The structure of a photograph can communicate before it is understood. A good image teaches one how to read it by provoking responses from the viewersí inventory of life experiences as meaning is not always found in things, but sometimes between them. An exceptional photograph creates viewer focus that produces attention, which can lead to definition. As one mediates on what is possible, multiple meanings may begin to present themselves.

9. Are the issues surrounding truth and beauty still relevant to photographers of the 21st century?

During the past twenty-five years issues of gender, identity, race, and sexuality have been predominant because they had been previously neglected. In terms of practice, the artistic ramifications of digital imaging have been a overriding concern. But whether an imagemaker uses analog silver-based methods to record reality or pixels to transform it, the two greatest issues that have concerned imagemakers for thousands of years – truth and beauty – have been conspicuously absent from the discussion. In the postmodern era irony has been the major form of artistic expression.

Although elusive, there are certain patterns that can be observed that define a personal truth. When we recognize an individual truth it may grab hold and bring us to a complete stop – a total mental and physical halt from what we were doing, while simultaneously experiencing a sense of clarity and certainty that eliminates the need for future questioning.

Beauty is the satisfaction of knowing the imprimatur of this moment. Although truth and beauty are based in time and may exist only for an instant, photographers can capture a trace of this interaction for viewers to contemplate. Such photographs can authenticate the experience and allow us to reflect upon it and gain deeper meaning.

Beauty is not a myth, in the sense of just being a cultural construct or creation of manipulative advertisers, but a basic hardwired part of human nature. Our passionate pursuit of beauty has been observed for centuries. The history of ideas can be represented in terms of visual pleasure. In pre-Christian times Plato stated: “The three wishes of every man: to be healthy, to be rich by honest means, and to be beautiful.” More recently American philosopher George Santayana postulated that there must be “in our very nature a very radical and widespread tendency to observe beauty, and to value it.”

10. How has digitalization effected photography?

Although Photovison is “dedicated to the pure craft of photography,” digitalization has shifted the authority of the photograph from the subject to the photographers by allowing them to extend time and incorporate space and sound. Photography is no longer just about making illusionistic windows of the material world or collapsing events into single moments. The constraints on how a photograph should look have broken down, they no longer have to be two-dimensional objects that we look at on a wall. This elimination of former artificial barriers is also good for those who wish to practice the art and craft of photography because it encourages makers to open the doors of perception to new ideas and methods for making photographs.

11. What are the advantages of digital imaging over silver-based imagemaking?

As in silver-based photography, digital imaging allows truth to be made up by whatever people deem to be important and whatever they choose to subvert. While analog silver-based photographers begin with “everything” and often rely on subtractive composition to accomplish these goals, digitalization permits artists to start with a blank slate. This allows imagemakers to convey the sensation and emotional weight of a subject without being bound by its physical conventions, giving picturemakers a new context and venues to express the content of their subject.

12. What are the disadvantages of digital imaging?

The vast majority of digital images continue to be reworkings of past strategies that do not articulate any new ideas. Manufacturers promote the fantasy that all it takes to be an artist is just a few clicks of a mouse or applying a preprogrammed Fresco or Van Gogh filter. The challenge remains open: to find a native syntax for digital imaging. At the moment, this appears to be one that encourages the hybridization and commingling of mediums.

On the practice side, having a tangible negative allows one to revisit the original vision without worrying about changing technology. One could still take a negative that William Henry Fox Talbot made to produce his first photographic book, The Pencil of Nature (1843 – 1846), and make a print from it today. In 150 years will there be a convenient way for people to view images saved only as digital files? Or will they be technically obsolete and share the fate of the 8-track audio tape or the Beta video system of having data that most people can no longer access?

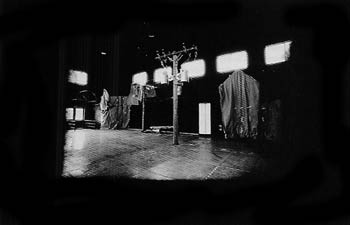

One does not have to be a Luddite to continue making analog prints. One reason to keep working in a variety of analog processes is that digital imaging tends to physically remove the maker from the photographic process. This is not a romantic notion or a longing of nostalgia for the ways of the past. What often lost is the pure joy of the atmospheric experience of being alone in a special dark room with an orange glowing light. The exhilaration of being physically creative as your body and mind work together to produce a tangible image. The making of an analog photograph is a haptic experience that does not occur while one is seated in a task chair. The smell of chemicals, the sensory experiences of running water as an image emerges in the developing tray from a white nothingness. A silver-based photograph never looks better than when viewed when it is glistening wet from its final wash. And regardless of how long one has been making prints in the darkroom, there is still that small thrill that your photograph “has come out” and now can have a life of its own.

13. A common complaint of some beginning photographers is that there is no artistic subject matter in their locale.

Today a central characteristic of imagemaking is not only to create objects (photographs), but also to escape the restrictive parameters of their objectness through content. However, it is a common misconception to link content solely with the subject matter being represented. Photographs that affect people may have nothing to do with the apparent subject matter, and everything to do with the subsequent treatment of that subject. This realization creates limitless potential for subject matter.

Light is a vital component of every photograph. This was recognized early in the medium’s history by William Henry Fox Talbot’s, The Pencil of Nature (1844 – 1846), the first book to be fully illustrated by his paper calotype process. Talbot’s selection of images, such as The Open Door, 1843, demonstrate his belief that subject matter was “subordinate to the exploration of space and light.” The quality of light striking a subject can reveal or supress its characteristics, which will make or break a photograph. Light may be natural or artificial, but without the appropriate type of light even the most fascinating subjects become inconsequential.

Ultimately light is a principal subject of every photograph that imagemakers must strive to control and depict. As Talbot stated, “A painter’s eye will often be arrested where ordinary people see nothing remarkable. A casual gleam of sunshine, or a shadow thrown across his path, a time-withered oak, or a moss-covered stone may awaken a train of thoughts and feeling, and picturesque imaginings.” This is the realization that the subject in front of the lens is not always the only subject of the photograph.

14. It’s been done before.

To accept the notion it has all been done before is to embrace clichés. The problem with clichés is not that they are erroneous, but that they are superficial and oversimplified articulations of complex concepts. Clichés are detrimental because they encourage photographers to believe that they have done a sufficient job of recording a situation when in fact they have merely gazed at its surface. The simple act of taking a photograph of Niagara Falls or a pepper is no guarantee that one has communicated anything essential about that subject.

Good photographers provide visual clues and information about their subject for the viewer to contemplate. They have learned how to distill and communicate what is essential to them about their subject. By deeply exploring a theme and challenging clichés, photographers can reconstruct their sight and gain a fresh awareness and understanding.

15. I’m not in the right mood to make photographs.

Responding to life with joy and sorrow is part of the human condition. At times when pain and suffering are inescapable, it is important to remember that this is part of the process by which we acquire knowledge. This does not mean that one must be in discomfort to make art, but stress can be channeled into a creative force if it produces a sense of inquisitiveness and an incentive for change. Thinking through making pictures can allow us to place our pain in context. The images we make can help us understand its source, catalog its scope, adapt ourselves to its presence, and devise ways to control it. There are things in life, once called wisdom, which we have to discover for ourselves by making our own private journeys. Stress can open up possibilities for intelligent and imaginative inquiries and solutions that may have otherwise been previously ignored overlooked or refuted.

16. I have no idea how I am going to make a photograph of this subject.

When you get stuck and cannot find a solution to your problem, try changing your thinking patterns. Instead of forcing the issue, go lie down in a quiet and comfortable dark room, close or even cover your eyes, and allow your unconscious mind a chance to surface. Other people may go take a bath or go for a walk. The important thing is to find something that will change your brainwaves. Anecdotal history indicates that this can be an excellent problem solving method — turn off the cognitive noise and allow your internal “hidden observer” to scan the circumstances, and then return to your normal state with a possible solution. Keep paper and pencil handy.

17. Why is it important to understand and be proficient in the technical skills of your medium?

Understanding the structure of the photographic medium allows one the freedom to investigate new directions. When first seen, an image may be exciting and magical, however the photograph needs to be objectively evaluated. To do this one must have the expertise of craft to understand the potential for that photograph. Mastery of craft allows one the control to be flexible, to sharpen the main focus, and discard extraneous material. This evaluation process permits an imagemaker to reexamine and rethink their initial impulse and jettison inarticulate and unadorned fragments, and to enrich and refine them by incorporating new and/or overlooked points of view.

An artist who invests the extra time to incubate fresh ideas, learn new technical skills, try different materials, and experiment with additional approaches can achieve a fuller aesthetic form and a richer critical depth. This procedure is often attained by reaching into another part of ourselves than the one we display in our daily demeanor, in our community, or in our imperfections.

18. How can a photographer make a difference in the world?

The desire to “see” implies that our sense of focus and beauty is not immobile and can be sensitized by an appreciation of previously neglected aesthetic qualities. The history of artistic photography is a succession of imagemakers who have used their intellectual and intuitive skills to convey what amounts to “Isn’t this fascinating!” Photographers who make a difference are those who are able to open our eyes and make us more aware.

19. Why is it important to make your own photographs?

The physical act of making a photograph forces one into the moment and makes you look and think more than once, increasing your capacity for appreciation and understanding. This not only allows you to see things in new ways, but can also be physically and psychologically exhilarating. It reminds us that life is not mediocre, even if our daily conception of it is. Making your own images allows photographers to forge their own connections between the structure of the universe and the organization of their imagination, and the nature of the medium. Consider what artist and teacher Pat Bacon says: make work… make it often…make it with what’s available!

20. How much visual information do I need to provide the viewer in order to sustain meaning?

There are two basic stylistic approaches for transmitting photographic information. One is an open approach in which a great deal of visual data is presented. It allows viewers to select and respond to those portions that relate to their experiences. The second method is the closed or expressionistic form. Here the photographer presents selected portions of a subject with the idea of directing a viewer towards a more specific response. Photographers need to decide which technique is most suitable for a particular subject and their specific project goals. Approaches shift depending on the project situation, but generally it is helpful to keep a constant approach throughout one body of work. Consciously selecting a single stylistic method for a series also provides a basic template for organizing your thoughts and producing work that possesses a tighter focus of concentration.

21. How much of a photographer’s output is likely to be “good”?

The American poet and writer Randall Jarrell wrote an apt metaphor that can be applied to other forms of artistic inspiration: “A good poet is someone who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times; a dozen or two dozen times and he is great.” When Ansel Adams was photographing on a regular basis he said he was satisfied if he made one “good” image a month. Much of any artistic practice is working through the process. Good artists take risks but also recognize that not everything they do is for public circulation. Situations that provide constructive and challenging criticism can be beneficial in helping to resolve a project. Over time, skillful artists learn to edit and critique their own work, presenting only their most thought-out solutions for public consideration.

22. How do photographers explore complex relationships of time, space, and scale and their role in generating meaning?

The process of making pictures involves keeping an open mind to single and serial image constructions, narrative and non-narrative formats, in-camera juxtapositions, and post-camera manipulations. Consciously ask yourself questions such as: How does image size effect viewer response? How would changing to black-and-white or color effect the image’s emotional outcome? Examine how one photograph may modify the meaning of the image next to it. Consider what happens if text is added to an image? How can meaning shift with a title as opposed to leaving a photograph untitled? What is the most effective form of presentation, and what is the appropriate venue?

23. Why study the history of photography?

History is an opportunity to learn the basic skills needed to critically examine photographs: description, interpretation, and evaluation. Encountering new photographs also presents the chance to articulate something in yourself that previously you had been unable to release. Often new visual experiences can trigger semiconscious thoughts that resurrect, from the deadness of routine and lack of concentration, valuable yet overlooked aspects of our experience.

24. What are the limitations in studying the images of others?

The French novelist Marcel Proust stated: “There is no better way of coming to be aware of what one feels than by trying to recreate in oneself what a master has felt.” While viewing the work of others can help us understand what we feel, it is our own thoughts we need to develop, even if it is someone else’s picture that aids us through this process. Regardless of how much any image opens our eyes, sensitizes us to our surroundings, or enhances our comprehension of social issues, ultimately the work can not make us aware enough of the significance of our predilections because the imagemaker was not us. Looking at work can place you at the threshold of awareness, but it does not constitute cognizance of it. Looking may open deep dwelling places that we would not have known how to enter on our own, but it can be dangerous if it is seen as material that we can passively grab and call our own. We become photographers because we probably have not found pictures that satisfy us. In the end, to be a photographer, you must cast aside even the finest pictures and rely on your internal navigational devices.

25. Can too much knowledge interfere with making photographs?

The answer is both yes and no. Beware of those who do not think independently, but rely upon established aesthetic, theoretic, or technical pedigrees as guides to eminence. You do not have to know all the answers before you begin. Asking questions for which you have no immediate answers can be the gateway for a new dynamic body of work. Do not get overwhelmed by what you do not yet know. Admit there is always more to know and learning should be a life-long process. Use your picturemaking as a discovery process, but do not allow the quest for data to become the central concern or a deterrent not to make pictures. Know-ledge of a subject can offer points of entry for visual explorations. Learn what you need to begin your project and then allow the path of knowledge to steer you to new destinations.

26. Is it necessary to explain my photographs?

Yes, it is usually vital to give viewers a personal perspective to your work with a concise and well-crafted artists’ statement. This also allows you to create a framework of understanding for your work.

27. What happens when visual experiences fall in-between words?

Words create their own environment of understanding, which can at times be limiting. In life, mystery and meaning are often intertwined. Albert Einstein said, “The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science. Whoever does not know it can can no longer wonder, no longer marvel, is as good as dead, and his eyes are dimmed.”

Meaning is uncovered by personal experience, being mentally alert and maintaining openness. By remaining accessible to different interpretations, viewers and imagemakers may discover meaning in the work that was not in their conscious mind. Photography can operate on that border where words fail but meaning continues.

Enigma also remains an essential quality of art making. English painter Francis Bacon, whose work was strongly influenced by photography, believed that the power of a work lay in its ability to be alluring yet elusive.

Bacon thought that once an image could be explained, sufficiently approximated in words, it became an illustration. He believed that if one cold explain it, why would on e go to the trouble of painting it? According to Bacon, a successful image was by definition indefinable and one sure way of defining it was by introducing a narrative element.

For centuries, storytelling was the backbone of Western art and it was the bourgeois coziness and shallow academic conventions of 19th century narrative painting that made storytelling anathema to the aesthetic vocabulary of modern art. Bacon took the existential position that his pictures meant nothing, said nothing, and he himself had nothing to say.

Bacon believed that painting was the pattern of one’s nervous system projected on the canvas. He wished to “paint like Diego Velazquez but with the texture of a hippopotamus skin,” achieving the tonal subtly inspired by the Spanish master who encompassed the rough, grainy immediacy of a news photo. He sought to exalt the immediacy of camera vision in oil, like a portrait in the grand European manner.

28. What is the role of critics and critique?

“Unless you are one critic in a hundred thousand,” wrote the critic and teacher Randall Jarrell, “the future will quote you only as an example of the normal error of the past.” The real importance of criticism is for the sake of the work that it criticizes. Good critics open space for creation and interpretation. They do not set up rigid agendas and templates or try to impose their own prescriptive notions. Superior critics allow time for work and the experience of it to set the general expectations to which the criticism conforms. Such critics can guide people to ask questions and find their own answers. They can facilitate a dialogue between the work and the viewer by clarifying and focusing everyday assumptions.

29. What is the role of theory in relation to contemporary photography?

It is a matter of individual perspective and priority. A conceptual framework can provide a system for understanding how and why photographs are made, understood, and circulated. For instance, a its best postmodernism’s agenda of inclusion creates a permissive attitude towards a wide range of interpretive possibilities. At its worst, it encourages a nihilistic solitariness where all expression resides in a haze of undetermined value. As a student, one does not expect to learn and unlearn photography all at once, but regardless of one’s personal inclinations, one should become informed about past and present artistic theory, from John Ruskin to Jacques Derrida, and how it has effected photographic practice.

30. What are the qualities of a good teacher?

A good teacher provides resourceful guidance and leadership that prepares individuals to tap into their own creativity to find their own answers. Good teachers are well organized, care about the subject and their students, and work to create a flexible give and take atmosphere. They encourage openness and a dynamic dialogue between the instructor and student(s). They are enthusiastic, patient, utilize good learning materials, and establish clear long term goals. Good teachers are accountable and honest in their responses to student work. They do not tear students down just to be provocative, but have students present and defend their ideas to understand the intention of the work.

Good teachers focus on everyday assumptions and encourage experimentation and realize that taking chances and stepping into unknown territory may result in a temporary failure that can often prepare one to go on the next level. Good teachers my teach by example but continue to advocate that students must find their own voice and not imitate. They ask adroit questions and listen carefully in order to navigate students toward information that will generate development of their aesthetic and critical thinking. Most importantly, good teachers impact their students by building confidence and instilling the belief that if they focus on the task at hand, think critically, and act specifically they can excel and succeed.

31. What are the qualities of a good student?

Good students have the will to learn. They are self-motivated and work for themselves and not to please others. They are alert, curious, enthusiastic, keep an open mind to new ideas, and enjoy the learning process. They set personal goals, maintain an organized work schedule, and properly manage their time. They assume responsibility for their actions and accept the challenge to think critically about the material. They prepare their minds by completing their reading and writing assignments so that they may ask questions and actively participate in group discussions in order to improve their base of knowledge. They are respectful and courteous to their teachers and fellow classmates and to differences of opinion. At the conclusion of their study they are able to demonstrate their knowledge and integrate it into their lives. WIth good fortune this can lead t a realization of where they are at the moment, where they would like to be in their future and how to adjust their lives to make it happen.

32. How do photographers earn a living?

Living as an artist depends on what you want to do and how much money you require. Less than one percent of artists live on what they earn from their artwork. Do not expect to get a full-time teaching job in higher education even if you are willing to work for years as an adjunct faculty at numerous institutions.

However, there are career opportunities in art and cultural organizations as well as in primary and secondary education. Take advantage of being a student to do an internship that will give you first-hand experience in an area you would like to work within. Successful internships can lead to entry-level jobs. The visual arts community is still a relatively small field. Hard work , networking and good collaboration skills are in demand.

They can earn you excellent letters of reference and create new bridges to your future that are at present unimaginable.

33. Now it is your turn. Add a question and answer to this list.