Truth of the Moment & Truth of Reflection

The invasion of Iraq raises questions about how journalistic images are made, circulated, and affect the way we see the world. All news photographs have a point of view that is determined by the aesthetic, cultural, and technical makeup of the photographer and the editorial process. In Iraq we were presented with an American story told mainly by American photojournalists embedded with the American troops. In exchange for such access journalists forfeited control of movement and became dependent on a controlled military environment. The editorial network responsible for delivering images to the public was also caught up by its own emotional involvement and patriotism.

People expect two things from credible photojournalists, photographic honesty in telling a story and a factual photographic record of what has happened. This is difficult since photography is subjective and news photographs filter

through numerous layers of interpretation before reaching the public. Journalism is not an externally regulated business so what constitutes fairness and truth varies widely. The Society of Professional Journalists has a voluntarily code of ethics (www.spj.org/ethics_code.asp), but this does not assure accuracy, and reliance on existing controls have been insufficient. The failure of such self-policing policies can also be seen in the ethical collapses of respected religious and corporate institutions from the Catholic Church to WorldCom where self-preservation and public perception took priority over the facts.

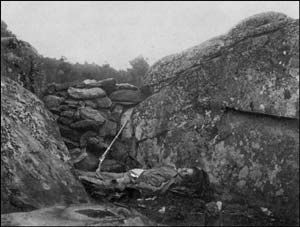

The oxymoron known as photographic truth has never been a fixed entity; rather it results from an attitude of seeking and building reality from a particular viewpoint at a specific time. As we can ascertain from Alexander Gardner’s Home of the Rebel Sharp-shooter (1863), photographic integrity is dependant on how society interprets the constructs of an image into its vocabulary of knowledge. During the American Civil War the technical limitations of the wet-plate process made it impossible to photograph actual battles and imposed a standard of photographic documentation that is different from now. Then it was customary for photographers to create a representation, both in and outside of the studio, to produce a desired reality. Gardner felt no compunction about rebuilding a scene for his camera to witness. He used artistic “effect” to deliver what he considered to be an accurate representation based on the foundation developed by painters and sculptors for depicting historical events.

Gardner arrived two days after the ferocious battle of Gettysburg and moved the body of a Confederate infantryman about 40 yards and added a Springfield musket (not a sharpshooter’s rifle) to the scene, and turned the corpse’s face toward the camera, thus forcing viewers to gaze directly into the tragedy that produced 51,000 casualties. Gardner’s war experiences guided his camera to bring forth an allegorical reference from a Northern perspective about the forlorn loneliness of the Confederate cause, making such photographs not so much evidence of history as history themselves.

In the twentieth century, W. Eugene Smith used flash, directed subjects, and performed darkroom heroics to achieve visual effects to create heroic humanistic photo-essays for Life magazine, which never mentioned his working methods. Yet in 2002, Edward

Keating was forced to resign from the New York Times for allegedly staging a photograph to illustrate a story surrounding the arrest of suspected terrorists in Lackawanna, NY. The photograph depicts a 6-year old boy, who is not an Arab, pointing a toy pistol in front of a sign reading “Arabian Foods.” Keating said that part of his craft was to prompt people to do things. In 2003, Brian Walski of the Los Angeles Times was fired for digitally compositing two photographs he had taken moments apart to improve the dramatic composition.

Right. © Laurent Rebours. Iraq Flag on Statue of Saddam, Baghdad, 2003. AP.

Is it fair to compare these actions with the outright deception of New York Times reporter Jayson Blair who fabricated and plagiarized war stories? Are such practices bad judgment on the part of the photographers that destroy the fragile bond of trust between journalist and the public or legitimate approaches? We often accept two kinds of photographic truth. There is situational reality, which is reserved for the times we realize that not everything needs to be real to convey a sense of truth and then there are other times when we demand to see the “unaltered” event that is supposed to depict the real sense of truth. Most people do not question the authority of Gardner or Smith’s work because we believe in their integrity to be true to the situation and in turn grant them artistic license to show us a reality we could not see for ourselves.

What about the reliability of images that result from situations when people are aware they are being photographed, such as the U.S. troops helping Iraqis tear down a statue of Saddam? As this scene was being broadcast live, the American flag that was first draped over the statue’s head was quickly replaced by an Iraqi flag, seemingly ordered by an invisible higher authority who did not want to give the impression that this was as an act of American imperialism. And let us not forget how images that result from constructed situations, such as President George W. Bush’s Top Gun landing on the deck of the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln, shape public perception. Are these different than the media fictions totalitarian regimes manufacture?

Is a discussion of manipulating a photograph a contradiction in terms? Is not the act of photography a manipulation of space and time, a presentation of a particular point-of-view as opposed to an empirical fact? What happens if we acknowledge that truth does not come in one-size-fits-all packaging? There is the truth of the moment, the act of witnessing, in which we want ethical photojournalists and institutions to tell a story as honestly as possible. This is because we believe that principled journalists have been in the thick of events and reflect Robert Capa’s working dictum: “If your pictures are not good enough, you aren’t close enough.” Then there is the truth of reflection, which gives us time and space to step back from the moment to deliberate and distill all our senses have told us about an event. This is a reverberation of Albert Camus’ position that “If we understood the enigmas of life, there would be no need for art.”

Most people benefit from both forms of knowing, but want them to be separate and clearly labeled. Delineating between the two can be tricky. Just as the technology of the 1860s defined photographic truth in that era, so now are digitalization and the Internet redefining how we know the twenty-first century. We seem to be coming full circle, giving image makers authority to again explore their subject with subjectivity both in and after the moment of witnessing. We need to be collective watch persons and make known how we wish the complexity of our existence to be photographically told. As history allows us to ascertain particular patterns, we should be aware that flux of photographic truth could shape-shift into different characters if we decide to let that happen.