Perceiving Photographic Truth

While working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the 1930s, photographer Arthur Rothstein made an image, Steer Skull, Badlands South Dakota, 1936. This started a controversy over the perception of photographic truth by moving a steer skull from one point to another (about 10 feet, according to Rothstein). Rothstein’s FSA mission was to show urban American’s desperate Dust Bowl conditions and garner support for Roosevelt’s social programs. However, politically motivated critics of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies charged that Rothstein misrepresented the truth by physically moving the skull, inferring that the FSA policies were phony socialist experiments. These conservative critics also are indicative of those who consider the expressive photographic approach to be a breach of the unwritten social contract that appoints the unmitigated photograph as the authentic gatekeeper of truth

The definition of photographic truth during the 1930’s was dominated by the notion that a photograph was an automatic process that could neutrally act as a stand-in for the viewer. In making Steer Skull, Rothstein presented a dramatized version of what he experienced by physically reorganizing the scene. Rothstein’s intent was to purposely and clearly visualize the situation, not to fool or fake viewers into mistakenly accepting a fantasy as truth. But some thought moving the skull was unacceptable because it was a deliberate distortion of the specific scene and not a found representation of it. However, what Rothstein did was to show that truth is an evolving concept based on how one processes the data at hand. He worked from the premise that he was “making” a characterization of the overall drought conditions as opposed to “taking” a news photograph of a specific drought.

Today the idea that a photograph can be a neutral container of facts seems naïve. We have come to realize that photographic meaning can be determined by how a photographer chooses to integrate content and compositional structure and that truth is not solely dependent on a literal transcription of reality. Such practices acknowledge that our world is complex and we cannot expect reductive, simplistic responses to provide satisfactory answers. For instance, photographer Nancy Burson’s recent exhibition Seeing and Believing at the Gray Gallery in New York City featured her “Human Race Machine,” which lets individuals see images of themselves using characteristics from other races. By making the viewer part of the process, Burson hopes that such images will remind people how much we all have in common. She says “The more we can see ourselves as each other, the closer we get to being one.”

Photographers who connect to viewers, such as Burson, recognize that the camera’s ability to indiscriminately record information can be directed to achieve specific audience responses. Photographers need to effectively use both their pre- and post-visualization skills (taking and making) to achieve a meaningful photograph that incorporates the external appearance and the internal nature of the subject. A viewer’s means of interpreting a photograph can be limited by their level of visual literacy. Nevertheless, the relevance of a photograph is determined by the viewer’s perception of how the silver crystals or pixels have been organized and whether they resonate with the viewer’s experiences.

Even digital imaging has not diminished people’s desire for truth based on unembellished physical evidence, which is why photographs continue to serve as the chief recorder of events. Making editorial choices and altering photographs is nothing new to photography. A famous nineteenth century example of such action is Alexander Gardner’s Home of the Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, 1863 in which he rebuilt the scene for the camera to convey the experience of war (51,000 casualties from July 1 to July 3, 1863). Since its invention photography has been manipulated to achieve a desired result and Home of the Rebel Sharpshooter suggests photographic truth has always been a popular misconception about how the process actually works. One can say that images such as Home of the Rebel Sharpshooter are more accurate because the photographer controlled the situation and directed viewers towards a predetermined understanding of an event.

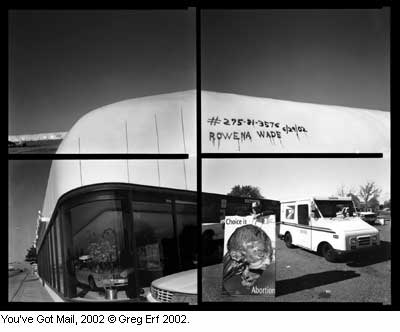

The concept behind Erf’s You’ve Got Mail, 2002 was to visually convey the heated viewpoints about abortion rights in the United States. Erf wanted to take into account issues that surround the public debate about pro-choice and pro-life including power, money, government, religion, conservatism, and liberalism. These include: when does life begin and what are the rights of women to control their own bodies? The 2000 U.S. presidential election magnified people’s extreme differences in regards to abortion rights, as did the bombings of women’s health clinics and the shooting of doctors who work in them.

In a conceptual manner similar to that of Rothstein, Erf’s construction, You’ve Got Mail, shows how a visual truth is formed by a series of conscious choices that result in a single photographic work. The first photograph Erf took is in the lower right-hand corner and it set the stage for those that followed. It shows a middle-age gentleman carrying rosary beads, quoting from Scripture, while standing behind a big poster of an aborted fetus in its third trimester. He was continually yelling at the people passing by on this early Sunday morning as they made their way to church. In the background is a U.S. Postal Service vehicle, which juxtaposes the rosary beads and implies the presence of both church and state within this issue.

The second photograph Erf made, lower left, was of a Cadillac dealership with two large white Cadillacs in the foreground. The white, monolithic Cadillac showroom interjects a sense of power, wealth, and conservatism. What made this environment important was how the white building visually blends into the sky of the first photograph and the happenstance of the white Cadillacs in the foreground. The white also extends a sense of pureness through both photographs that provides a unifying compositional device.

The remaining two photographs follow the thematic use of white and monolithic form to continue the feeling of a larger-than-life spirituality. Erf physically added lines to the white structure in the third picture, top left, to formally connect these two monolithic forms. The last picture, top right, is a continuation of the white form with the addition of a Social Security number, name, and date that insinuates the plight of a particular individual.

Rothstein’s and Erf’s photographs directly speak to social and political truths by referencing reality rather than acting as substitutes for it. These photographs remind one how meaning can be evoked as well as meticulously described, that unadorned appearance is not necessarily the same as truth, and how being rigid produces a narrow, inflexible interpretation of the world.