Oil & Water: Avedon and Winogrand

By Robert Hirsch and Greg Erf

From Photovision Magazine, July/August 2003

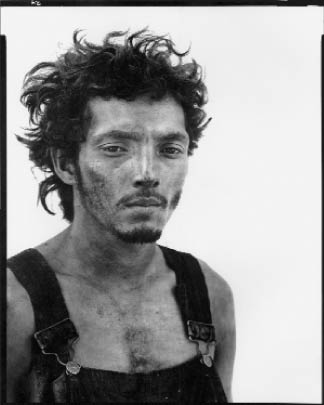

“Roberto Lopez, oil field worker, Lyons Texas”,

September 28, 1980 59 5/8 x 47 1/8 inches

Collection of the artist, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

This past fall in New York City one could view two highly divergent approaches to photography as The Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibited Richard Avedon: Portraits and the International Center of Photography presented Winogrand 1964. This dichotomy is vividly expressed in their artists’ statements. Avedon’s [1923 – ] reads: “I’ve worked out of a series of no’s. No to exquisite light, no to apparent compositions, no to the seduction of poses or narrative. And all these no’s force me to the ‘yes.’ I have a white background, I have the person I’m interested in and the thing that happens between us.”

On the other hand, Winogrand [1928–1984] said: “I look at the pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and how we feel and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty. I read the newspapers, the columnists, some books, I look at some magazines [our press]. They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn’t matter, we have not loved life. I cannot accept my conclusions, and so I must continue this photographic investigation further and deeper.”

The Avedon exhibition at the MET was a beautiful gray walled installation without glass in front of the photographs to interfere with viewing his Harper’s Bazaar work from the 1940s to The New Yorker work of present. It’s sleek and elegant atmosphere reinforces Avedon’s 1940s glamour aesthetic and allows one to soak in the artistry and the empirical surface detail and scale of his work.

In contrast, Winogrand’s big, maybe too big, tightly hung show of over 150 photographs made in 1964, clearly demonstrates his thought process. Winogrand exposed 550 rolls of 35mm film during 1964 (about 20,000 frames), from which he made about a thousand 11×14 inch prints. The straightforward installation is without fanfare and puts the focus on Winogrand’s extension of the social documentary approach.

These two photographers, along with their presentations, could not be more different with Avedon’s focal point directly on the external form and Winogrand’s on the internalized content. Together these photographers represent both the oil and the water of our photographic conscience.

Neither cities nor the landscape are the primary concern of either photographer. Avedon disregards everything, except his own intentions, to create monolithic Renaissance style archetypes, whereas, Winogrand’s photographs reflect vitality of people struggling to create order out of chaos. Winogrand flamboyantly used the camera to insert himself into situations where people are driven by their passions. Avedon’s work feels like a calculated, cold-blooded examination of a collector who is pinning personalities onto photographic paper. Avedon’s photography is the means to produce high fashion “images” while simultaneously making himself a celebrity too.

Avedon’s In The American West, first shown in 1985, is the most problematic series in the show. These portraits are Avedon’s opposites—unemployed, unglamorous, oil field workers, waitresses, and drifters. The elite means of production had Avedon’s assistants rounding up individuals with a certain road-weary look and bringing them to his portable studio. Here Avedon applied his “Hollywood” understanding of the human psyche to briefly get inside their heads, provoke a response and then move on to the next wounded subject.

Copyright 2003 Estate of Garry Winogrand and Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, Courtesy of Arena Editions.

The American West images come across as cynical, condescending and insincere. His well-lubricated formula, sponsored by Mobil Oil, relies on the predictability of large-scale prints to overwhelm viewers. Avedon was the tourist gone westward with a privileged eastern mentality who imposed a previsualized template of “style” on each subject.

Avedon’s predetermination makes the desire for control the actual subject of his photographs. No photography is permitted in his exhibitions. The press is only allowed to reproduce certain images. Written commentary must be pre-approved before he will grant reproduction rights for his images. Such censorship is not a healthy practice for critically examining the long-term merits of any artists work. The MET show overreaches by pushing Avedon’s position from a connoisseur fashion photographer to a high art photographer, while ignoring whether his notion of the “image” really has the merits he thinks it has.

Of the same generation, Garry Winogrand’s show 1964, organized by the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, is the polar opposite of Avedon. His picturemaking strategy came from his internal compass and not a program of do’s and don’ts. This open discovery process allowed each picture to discover its own form. Winogrand was driven and made photographs for the sake of making photographs, even when he had no idea where they might take him. His approach was highly cinematic in that he made many exposures and later edited with a vengeance. Winogrand had a haptic sensibility and used his body like a gauge to register everything he encountered.

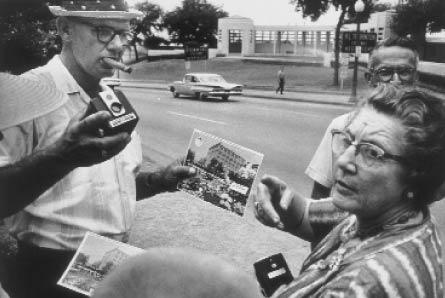

The work of 1964 remains refreshing and even naive because there are no guiding theories or fancy words of justification. In 1964 Winogrand was an artist on a roll. His work is inspiring simply because of the sheer number of memorable photographs he made in just one year, mainly during a four month coast to coast road trip. Winogrand was the quintessential lone ranger who scouted his own subjects. In Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Winogrand instinctively inserts himself in a situation in which people are trying to rely on the witnessing power of a simple Kodak camera and a picture postcard to make sense of trauma surrounding President Kennedy’s assassination. It is the “thereness” of this precarious balancing act that viscerally communicates the unknowableness of the events.

Winogrand’s off-kilt compositions made from oblique angles come alive with the implied actions and scenarios that occur outside the picture frame. His complex and fluid arrangements reflect the fragmented nature of American life and were genuinely shocking because they did not look the way good photographs were supposed to look. The intensity of Winogrand’s photographs comes from a hyperactive, untidy, noisy mania that is everywhere and all-at-once, passionately communicating the chaos of life and helping redefine the aesthetic of social art photography in the 1960s.

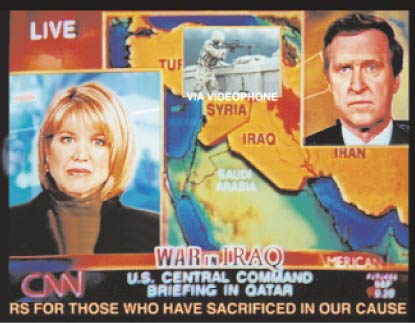

Today Winogrand’s complicated structural influence can be seen on the Cable News Network (CNN) that simultaneously presents multiple events within a single television screen. We see Paula Zahn in CNN’s glass backed New York studio discussing life and death events with retired generals in Washington, D.C. along with live feed from a reporter in Iraq on a videophone. This occurs as scrolling text runs below the streaming images and people wave in the background on their way to Starbucks.

With the sales of cell camera phones expected to surpass those of digital cameras this year, we are likely to see more such Winograndest visual splinters of reality entering and changing our perceptions of people and events. Winogrand’s chaotic and energetic vision was ahead of the curve in presenting the messy multi-levels of our social landscape while Avedon’s model reflects a narrow simplicity that now seems quaintly past. Today it is Winogrand’s visual syntax that continues to directly speak to us about the disorder and emotional shock and awe of the everyday.

Each exhibition is accompanied by a skillfully produced catalog. Richard Avedon: Portraits, Essays by Maria Morris Hambourg & Mia Fineman, and Richard Avedon, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0810935406, is an intriguing accordion style book that provides many of the key images from the show. Winogrand 1964, by Trudy Wilner Stack, Arena Editions, ISBN 18920 41626, reproduces every image from the show, each on its own page, and includes rarely seen color work.