The Tumultuous Fifties: An Interview with Douglas Dreishpoon

Robert Hirsch: How did the concept for The Tumultuous Fifties: A View From the New York Times Photo Archives originate?

Douglas Dreishpoon: My friend Nancy Weinstock was the keeper of the New York Times archives in 1996, and I went there to visit her. Entering the space I was immediately captivated and by the end of the day realized it was a treasure trove waiting to be mined. Among the millions of photographs kept in hundreds of file cabinets, Nancy showed me vintage prints of the Wright Brothers&Mac226; momentous flights at Kitty Hawk, Admiral Perry’s expedition to the North Pole, and absolutely pristine prints of WWI battle scenes. I left knowing that I wanted to do a project with the archives and chose the 1950s because of my professional interest in that period and its correspondence with my childhood.

RH: How did your collaboration on this project with Alan Trachtenberg, Professor Emeritus of English and American Studies at Yale University, begin?

DD: Born in the Fifties, I wanted to collaborate with someone who had lived during the period and had studied it firsthand. Being a cultural historian, Alan has worked extensively with photographs and has an astute pair of eyes. So I enlisted him as my co-curator. It was Alan who suggested we organize our findings into thematic constellations. Together with Nancy, we spent three whirlwind weeks in the archives and selected 500 photographs. From this first pass, we gleaned 200.

RH: How do the archives function and how did you start thinking about how such images can affect cultural representation?

DD: The archives are organized by subject file. Since the objective was to create an exhibition about the Fifties from multiple points of view, we were not necessarily looking for published images. During the Fifties the Times relationship with photographic images was not entirely friendly. The written word was golden. Most news editors believed that writers worth their salt could describe an experience so people could visualize it without a photograph. This put photographs at a huge disadvantage.

The photo editors of that decade had to defend the use of photographs in a zone called the “bullpen,” where senior editors from all news departments (local, national, international) met to decide what stories and images got published. The archives are a repository for all kinds of images from various sources—news agencies, departments of government, corporations and public relations firms worldwide. Only a tiny percentage of these were published, which depending on the image, its caption and placement in the paper, certainly would have influenced how specific events were perceived by the Times’ readership.

RH: Why did you decide to use vintage prints instead of new copy prints?

DD: Vintage prints tell you things that contemporary copy prints cannot. The surface of a vintage print has a distinct quality; it carries editorial marks —crop marks and wax pencil lines, as well as airbrushing—that reveal how it was prepared for publication. For example, in Sam Falk’s photograph of Ethel Rosenberg riding in the front seat of an FBI car, airbrushing was subtly used to diffuse areas around her so when the image was published she would visually project.

RH: Can you summarize some of the socioeconomic themes of the Fifties that you observed?

DD: The themes we set up as “Growing up American,” “America in the World: War Hot and Cold,” “Mechanization in Command,” “American Ways of Life,” and “Fame and Infamy,” allowed us to address cultural tenets that distinguish the period. There were surprises, too, especially when it came to cultural phenomena presumed indigenous to the 1960s, though spawned in the Fifties, such as rock’n roll, civil rights, radical youth culture, and the women’s movement.

RH: The Fifties was a time of great contrasts between the nuclear war culture and the booming economy and, philosophically, between existentialism and the American transcendental way of thinking. Do you think your exhibition gives people a toe-hole into that atmosphere?

DD: You’ve basically summed it up. We stereotypically know the Fifties as the decade of conformity and consensus, of postwar bliss and prosperity shadowed by lingering doubt and fear. The very conflicts and contrasts you’ve mentioned created the tumultuous environment that was the decade.

RH: What photographs stand out as being personally meaningful for you?

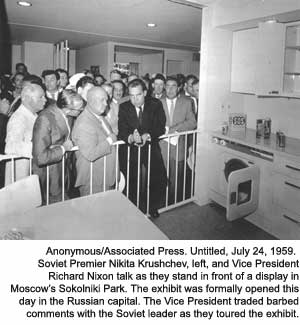

DD: The one of Vice-President Nixon rhetorically squaring off with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park at the American pavilion of the 1959 World’s Fair. They are standing with a large group outside the “Washer Room” of a simulated American home debating the state of culture in America versus Russia.

Nixon seems to be lecturing Khrushchev about Americans having a superior quality of life because many have access to affordable comforts. Khrushchev appears to respond with an incredulous look that says, “you’ve got to be kidding me.” This intense dialog between two world powers encapsulates the political dynamics of the Fifties ideological cold war.

Another is the photograph of Major John Glenn kneeling in front of his family with his “Project Bullet” fighter jet towering above them. The pyramidal composition of the photo, taken by Allyn Baum, creates an iconic image of American life—Glenn as the “right stuff” poster boy before the U.S. had initiated its manned space program.

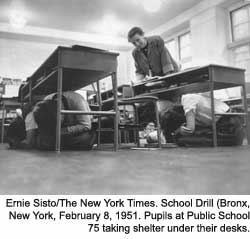

The third photo, taken by Ernie Sisto, is of children at a Bronx public school going through a “duck and cover” exercise monitored by their teacher. This useless exercise, intended to make you feel effective, reveals just how naïve we were at the dawn of the atomic age.

RH: How did this atomic culture affect people?

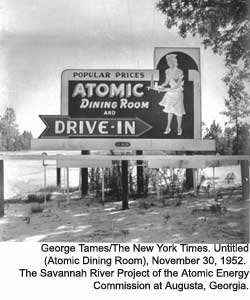

DD: The ever-present fear of attack lead people to build fallout shelters. Yet the flip side of this paranoia is embodied in a photograph taken by George Tames of a roadside billboard in Georgia that reads “Atomic Dining Room and Drive-In.” You have to ask yourself, what is this image about? The word atomic immediately sends shivers up your spine and here it is associated with food and dining. I remember eating one-cent “Atomic Fireballs” as a kid. Here was something “atomic” that you put in my mouth. On some level, this unlikely association was, I think, a way to humanize an otherwise deadly force that had become part of our daily lives.

RH: How does the captioning of news photographs create meaning?

DD: Captions are integrally connected to news photos. They’re married so to speak; you can’t have one without the other. Captions are frequently rewritten depending on the context they appear in and who’s editing the piece. They heavily influence your perception and understanding of what an image can mean.

We decided early on to use the original caption adhered to the back of each print. We also resolved to frame each caption with its image, right underneath, as opposed to having each one transcribed as separate label copy and displayed outside the frame. We wanted people to be able to read and to look as though they were reading the paper.

Captions are organic entities, constantly in flux. An image may be worth 1,000 words, but the succinct caption directs its meaning. Written by photographers, editors, and editorial assistants, each caption introduces a triangulation of possibilities. One should be aware of this dynamic, because it’s often presumed that a caption is the final word. But variations are possible, too.

RH: How has digital imaging effected preservation and the perception of photographic truth in news images from the 1950s to 2002?

DD: Digital archiving raises many questions, especially when it comes to preservation. It may come to pass that the most stable object is the paper print. News photographers have come to embrace digital photography because of its speed and ease of use. In terms of archival practice, digital photography renders the paper print obsolete. It also introduces “pixilation,” which throws a curve ball into the integrity of photojournalism.

The Times recognizes the degree to which digital methods can subtly and/or dramatically alter an image, and they’re pretty clear about what constitutes acceptable ethics. We often presume the photograph to be truthful, even though it’s a representation of something. Since photography’s invention in 1839, photographers have been manipulating their images, making the notion of a truthful image a relative proposition.

The Times archives is a treasure trove because of the images’ cultural significance and the inherent stability of vintage paper prints. The main difference between inkjet and silver images revolves around the print’s surface—its skin.

The digital print can be highly manipulated whereas the silver print, at least on the surface, remains inviolable. The skin of the analog print may carry crop marks and airbrushing, but even with these procedures, it remains uniform, intact. Digitalization allows one to fragment and disrupt an image in ways that violate its integrity. There’s a holistic aspect to a Fifties vintage print in spite of surface alterations. Digitalization may be representative, on some philosophical level, of the grand fracturing of assumptions. We live in a collage world where things are cobbled together from numerous and potentially incongruous sources. It’s a composite world, especially in the visual realm, and nothing can be taken for granted.

RH: How has the concept of rapid fragmentation been injected into society?

DD: The fragmentation of the world into thousands of particles may well be connected, at least symbolically, to the dropping of the atomic bomb, which marked a significant reordering of cultural sensibilities and our perception of the world. TV, a postwar Fifties phenomenon, also altered the way people view things, especially to the degree and length of one’s concentration.

Those brought up on MTV’s rapid edits may have a harder time concentrating on anything stationary. Could it be that one’s physiological system responds to different kinds of time based on what they’re looking at, playing with, and listening to? Fragmentation through digitization also affects the way music is composed and played today. The difference between “sampled” sounds and CD bands as opposed to, say, the grooves of a vinyl album.

RH: How has this affected the camera’s place in our lives?

DD: There seems to have been a greater continuity to life during the Fifties. We were certainly more innocent, and this plays out in people’s acceptance of photography. Alan and I found many photographs with multiple cameras in them. That is, cameras that belonged to photographers other than the one who shot the picture. These images suggested to us that the camera had become a ubiquitous part of the cultural landscape and that people were more tolerant of its presence and less concerned about their privacy.

Today, we are more skeptical and paranoid about the camera’s ability to capture us at vulnerable moments and how the image might be used. A photographer’s access to a particular event is no longer guaranteed. In fact, in many instances, access is greatly limited.

RH: In terms of the photographer acting as a surrogate witness, what percentage of the images selected were made with a 4 x 5-inch Speed Graphic camera?

DD: Most of the Times staff photographers used the Speed Graphic until the end of the Fifties, when they finally gave it up for the more portable Rolleiflex.

RH: Does a larger camera give the photographer a greater aura of creditability?

DD: People come to accept certain equipment as pro forma. To show up at an event during the Fifties with a Speed Graphic, number four peanut bulbs, and a Mendelsohn flash, gave the immediate impression you were an authentic press photographer, like wearing the appropriate bobby socks to the dance, even though by the decade’s end such bulky equipment was considered passé in many journalistic circles.

RH: Why did these photographers favor the larger camera?

DD: Many preferred the print and tonal quality of the larger negative. Eddie Hausner, a staff photographer during that time, told me that with the Speed Graphic, he had to make that first shot count, even when using a manually operated fourteen-sheet film magazine. He was always careful to frame that first shot—what he described as “the lead picture, the gravy shot.” After that crucial shot, others were icing on the cake.

Douglas Dreishpoon is curator at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, NY. He and Alan Trachtenberg co-curated The Tumultuous Fifties.

An illustrated 278 page catalogue The Tumultuous Fifties: A View From the New York Times Photo Archives accompanies the exhibition with essays by Luc Sante, Alan Trachtenberg, and Douglas Drei-shpoon. It is available from Yale University Press (ISBN 0-914782-99-1) for $39.95.

Exhibition Schedule

After the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, The Tumultuous Fifties: A View From the New York Times Photo Archives travels to the following venues:

- The New-York Historical Society, April 30 to August 30, 2002.

- Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, October 12 to December 15, 2002.

- CU Art Galleries, University of Colorado, Boulder, January 23 to March 23, 2003.

- Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, May 2 to July 13, 2003.

- University Gallery, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, September 13 to October 26, 2003.

- Terra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois, December 12, 2003 to February 8, 2004.

- National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., March 12 to May 9, 2004.

- Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, June 12 to August 8, 2004.

- Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, Gainesville, September 5 to November 28, 2004.

![]()