Light and Ink, Bill Owens: Photographing the Suburban Soul

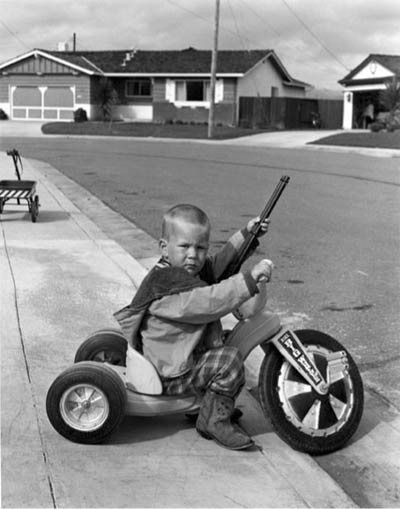

Bill Owens’s Suburbia (1972) is a quintessential photographic study of suburban California life and of its rituals. Owens followed with Our Kind of People (1975), which examined political, religious, scholastic, and sports groups and their practices. Then he published Working: I Do It for Money (1977) that looked at people who work from nine to five. In 1976, Owens received a Guggenheim Fellowship and, afterwards, two National Endowment for the Arts awards. Between 1978 to the 1982 he was a freelance photographer and did work for magazines including Life and Newsweek. In 1982 Owens started Buffalo Bill’s Brewery and published American Brewer Magazine (1984 – 2001). In 2004 Owens added to his visual anthropology cycle of the American middle class with the publication of Leisure: Americans at Play. Currently, Owens is making mini digital movies about America society. This piece is the result of conversations and emails between Owens and the author from December 2004 through March 2005.

Robert Hirsch: How did your personality allow you to do your suburban projects?

Bill Owens: My mother worked in the shipyards and my dad was a construction worker. Neither graduated from high school, but my dad always told me to learn from everybody. My mom had the gift of gab and made friends with everybody. They gave me a personality of a natural salesman, one who can project his personality. My photography is successful because I sell my ideas and myself to people. I speak well, I am direct, I carry myself professionally, and I don’t use the F word too often.

RH: How were you different from other kids?

BO: I was dyslexic and didn’t read. I skimmed comic books. I was at the bottom of the class. No one would have predicted I would succeed at anything, but I am proof one can grow and mature. We can expand our intellectual capacity and our intellectual compassion, which is why I have a problem with our president; I don’t see much human compassion in him.

RH: How did you overcome your dyslexia and learn to read?

BO: I took a class from John Gardner and he made me realize I was a good storyteller, but I flunked out of college and hitchhiked around the world. I came back a changed individual and started taking remedial courses. Now I brag I have Attention Deficit Disorder. I take credit for everything. Why not? It doesn’t mean a damn thing in life. All it does is brand you as being different. And sometimes you can wear that badge of difference proudly and say screw you.

RH: Why did you join the Peace Corps?

BO: I was raised in the Quaker church. We were socially concerned and believed in tithing to help the less fortunate because that is what the Bible preaches. In college I took part in anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and when I graduated I wanted to do something positive. I thought being a teacher in a foreign country would allow me to contribute something to the world at large and learn more about life.

RH: How did you decide to start making photographs?

BO: While I was serving in the Peace Corps in Jamaica during 1964 a photographer came through and changed my life. I watched him work and decided I would love to do that too. I bought $10 Leica with a pinhole in the shutter and put shoe polish in the pinhole so the photographs wouldn’t have a little white spot. I discovered I had a natural eye. I switched to a Nikon SLR so I could see the exact image I was getting and before I left the Peace Corps I had my first photography exhibit.

RH: How did you encounter John Collier [author of Visual Anthropology: Photography As a Research Method (1967)]?

BO: I went back to school at San Francisco State and took a visual anthropology class with John Collier during 1967 -1968. He wanted us to do community studies. Every Thursday I would go to the little town of Brisbane, south of San Francisco, and photograph. I would shoot along Main Street and go to Cub Scout meetings. I made a shooting script, as I had been taught to do in his class, and started to lay down the stuff that eventually evolved into Suburbia.

RH: Does this approach still interest you?

BO: Yes, I am planning to digitally photograph Starbucks, which is part of the new suburbia. I don’t care to go back and photograph a Tupperware party again. The new demographics of our commercial society, the Dollar Store, Home Depot and Cosco, are right in front of my nose right where I am living and that is what I want to photograph.

RH: What intrigues you about digital imaging?

BO: When photographers hold a 35mm camera up to their eye they are looking through a straw. The digital camera gives you a screen to watch. When making my new digital mini films, I hold the camera out in front of me and I have a 180-degree vision. I can anticipate what is going to happen in front of the camera and just let it happen. You can see the world and the camera simultaneously. You are no longer looking through that straw and can anticipate where to move the camera.

RH: What about Photoshop?

BO: Photoshop is not in my vocabulary. I don’t need it because I have content. You need Photoshop when you’ve screwed it up.

RH: Would you use digital video in your new project?

BO: You know where I am going! I am going to be a documentary filmmaker. I’m flipped out over dovetailing the small image into the moving image back to the still images. It is also about sound. We lay our film out using iMovie and then go online and get music. Now I am making a mini film, 64 Degrees of Separation, for the New Orleans Museum of Modern Art.

RH: How much directing did you do?

BO: I have never directed much. Take the Tupperware party picture, there was no directing at all. I try and find the “right” position and pray the action unfolds in front of me.

RH: Will people devote the time to look at these mini films?

BO: I’m not going to worry about it.

RH: Do you still want to make books?

BO: Yes. A book is a physical object that you hold in your hand, carry around, and put on a shelf. The books on my coffee table include: Keeping Food Fresh, Germs, Medieval Kitchen, Generation Kill, The Power of Gold, Professor and the Mad Man, 1000 Years on a Hot Stove.

RH: Why the food books?

BO: I am doing a book on food because the photographs in the food magazines are too perfect. I am going to be the anti-Christ of food photography and show people the way that it really is. The first cut is done. It’s digital and fun.

RH: What about photography books?

BO: The only photography book is Motel Fetish (2002) by Chas Ray Krider. My favorite photographer is Yann Arthus-Bertrand, who did Good Breeding (1999), because he does his research and makes straight photographs of people and their animals.

RH: What previous work influenced Suburbia?

BO: I poured over Russell Lee’s Pie Town and the FSA images because they understood form. Everything has been done, but you draw inspiration. John Collier told me to open up the knife and fork drawer in people’s kitchen. I kept looking, looking, looking. I opened over 100 knife and fork drawers until I found the one I was searching for. All the symbols, from the corkscrew to the knives and forks, were there and properly arranged plus there is a toaster, an electric can opener, and blender in the background, and the counter is clean. This image was the result of studying those who came before me.

RH: Why did you switch to color in Leisure?

BO: Color offers another level of content, more texture, and more going on in general.

RH: Why did it take 30 years to complete your suburban project?

BO: I was married, had kids and responsibilities and couldn’t make a living in photography.

RH: I thought you would have made it.

BO: I had a slice of the pie, but advertising agencies weren’t interested in Suburbia. I may have documented the essence of the American soul, but advertisers didn’t want those kinds of images. I do not consider advertising pictures to be “photography”. When you are paid to do it, it’s not you; it’s them making the picture. They control what you want. Recently I did a New York Times assignment and it scared the crap out of me. They send you a shooting script telling you what they want, you provide that image, and that’s the end of that. It is work for hire. You can’t turn around and declare it is now suddenly art. There is a real difference between work for hire and what you see and respond to when you drive down the road.

RH: Has anything changed for those wanting to make social statements and meet their family obligations?

BO: No. I’m a socially concerned photographer ala Robert Capa. I wanted to change the world and make it better. It comes from my fascination with culture. I wanted people to be aware of the crass consumerism of the American culture, but young people are not taught to have social concerns. The emphasis is on being financially successful. Plus there is too much to do, and people can’t sort it out. Look in the Sunday paper, and there are a zillion things to go do. Why be socially concerned when you can go out and have fun?

RH: Would you become a photographer today?

BO: I don’t know that I would. I have been in the brewing business and now I’m president of the American Distilling Institute.

RH: What happened to Buffalo Bill’s Brewery?

BO: It’s still going, but I sold it in 1998. Sixteen years was enough. I had to be open 18 hours a day, 7 days a week. It’s way too draining.

RH: How do you respond to the critique that most of the people in Suburbia are white?

BO: That’s what the suburbs were and are. Near me now is Chinese suburbia, but you cannot tell the difference. They shop at the same stores. In my town we have a Buddhist temple next to a mosque and a half-mile down the road is a Catholic cemetery. Only in America can those things co-exist. That is the beauty of it.

RH: What about where you live now?

BO: Here in Haywood, CA we have about a 55 percent minority population consisting of Mexicans, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese. It’s a cross-cultural experience. It’s good, and we should get on with that.

RH: Do you think the desires in suburban areas have changed over the last 30 years?

BO: No. We live in a society that is inundated by the materialism. People are still getting married, having children and need a washer and dyer and two cars in the garage.

RH: How long did it take you to photograph Suburbia?

BO: I was married, and I had a child. I selected one day a week to shoot for a year; 52 Saturdays and I got it done.

RH: What did you learn as you went through the photographic process?

BO: I would study the contact sheets and prints and then go back to the John Collier shooting script again and look for the holes, the places where I failed. For instance, I didn’t include a birthday party. I went to a few and they were totally chaotic. Finally the right moment unfolded and I was out of film. By the time I reloaded the camera the moment was past and I didn’t have time to go to another party. It was also critical to review the shooting script to see if I got the right overview. It takes months to find it. You have to keep making sure you have the long shot, the medium shot, and the close up.

RH: Did you think cinematically?

BO: You might say that, but I never studied movies. I got it from John Collier’s Visual Anthropology: Photography As a Research Method. Collier not only discussed land use, but also introduced me to the concept of ecology.

RH: How much of this thinking was influenced by Roy Stryker?

BO: It’s all commingled, but Stryker didn’t write the book. I was raised on a farm and we would get together with our neighbors at the community center for potluck dinners. That was the beginning of it for me, that sociology of a community.

RH: Do you see Starbucks functioning as our new community center?

BO: Absolutely. I belong to the local chamber of commerce. It takes time to know everybody in your community. When I go downtown and I go to Joe the barber, Joe knows me because of my brewery and my antique store. I am part of the fabric of this town. They know me.

RH: How did your business skills enable you to do Suburbia?

BO: I am interested in structure. I know how to organize, plan, and make things happen.

RH: As in Documentary Photographer: A Personal Point of View (1978)?

BO: Yes, It was self-published and includes my Guggenheim application, how to write a grant, and how to do a shooting script. I show how to use a strobe and what happens when you don’t. “Dark light” gives a different meaning to a photograph and dark photographs don’t fly for Suburbia. You want the strobe lights to make the image well lit so that it can easily be read. I also put out Publish Your Photo Book: A Guide to Self-Publishing (1979).

RH: What other books influenced your working style?

BO: The Life Library of Photography (1970). In one of the books the editors compared two photographs of a hardhat construction worker. One made with 35mm and a second with 2-1/4. The 35mm image appears menacing while the 2-1/4 looks “documentary.” There are more tones and texture, and it communicates a bigger meaning. It convinced me to jump to the 2-1/4 format. For me it was critical to have the subtlety of the flash fill and bare bulb flash with the Pentax 6 x 7 negative, a combination that brought out detail and depth. This made the pictures open and non-threatening. Had I shot Suburbia with 35mm it would have communicated a very different meaning.

RH: What is important for young people in the field to know today?

BO: I don’t know how you become a photographer. There are many fabulous young photographers producing at a high level of sophistication, but can they last 30 years? It’s not a normal life. You have to travel a lot and make work to please others. Nothing drives you crazier than working on an assignment and then having the client hate your images. I have a Christopher Morley adage on my wall: “There is only one success: to be able to spend your life in your own way.” I’ve lived it my way.

For more on Bill Owens and to see some of his mini movies visit: http://www.billowens.com

![]()