Arthur Tress: Documentary Fiction

Arthur Tress is an American experimental photographer who utilizes his anthropological background to construct astonishing, dream-like expressions of his interior landscapes. Tress’s fictions, made up of ordinary objects set in commonplace environments, are organized to reveal their underlying psychological associations. Tress’s direct involvement with his subject matter generates tension between the formalism of the photograph and the subjectivity of his personal vision, creating a new hybrid form: documentary fiction. The resulting unexpected juxtapositions construct surrealistic non-sequiturs in which outer reality merges with the inner mind. The following is a distillation of recent exchanges between Tress and myself.

Robert Hirsch: How has your background affected your imagemaking?

Arthur Tress: I was born in Brooklyn in 1940. While attending Abraham Lincoln High School my older sis- ter, Madeliene, gave me a Rolleicord camera. I began taking pictures in the Brighton Beach area of the old amusements parks and dilapidated buildings of Coney Island and the cultural life underneath the elevated subway. As soon as I picked up this camera I had a surreal and dream-like emotional response to the remarkable juxtapositions of this fairly poor area that was informed by my liberal Jewish social consciousness I learned from my parents. I was captivated by the Magic and Social realistic artists, such as George Tooker, and surrealists, like René Magritte, whose works I saw at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum. I always felt like an outsider so even my early pictures have a sense of melancholic alienation to them, which I attribute to my Jewish heritage of the ghetto and the Holocaust. My father’s brother was a Hassidic rabbi who started an organization during World War II that saved thousands of Jews. Additionally, I experienced what I would now call a sense of gay alienation. I knew I was different than the other kids, even though there wasn’t such a word as gay at that time, which gave me the emotional direction for making these lonely landscapes.

RH: What else has influenced your way of seeing?

AT: My extensive photographic travels to places including Africa, Appalachia, India, Japan, Mexico and Sweden, which lead me to become a self-taught ethno-graphical photographer. Visually, I was deeply influenced by black-and-white cinematographers, such as Gregg Toland who photographed Citizen Kane (1941), Eduard Tisse who did the Battleship Potemkin (1925), Boris Kaufman who was the cinematographer for On the Waterfront (1953). Plus, the photographers of The American Social Landscape, including Bruce Davidson, Robert Frank and Danny Lyons who depicted bigotry and inequality, inspired me.

RH: Tell me about latest book and exhibition San Francisco 1964.

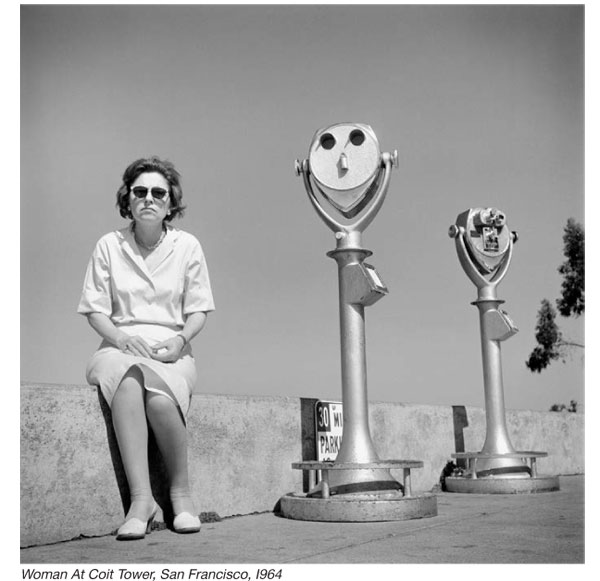

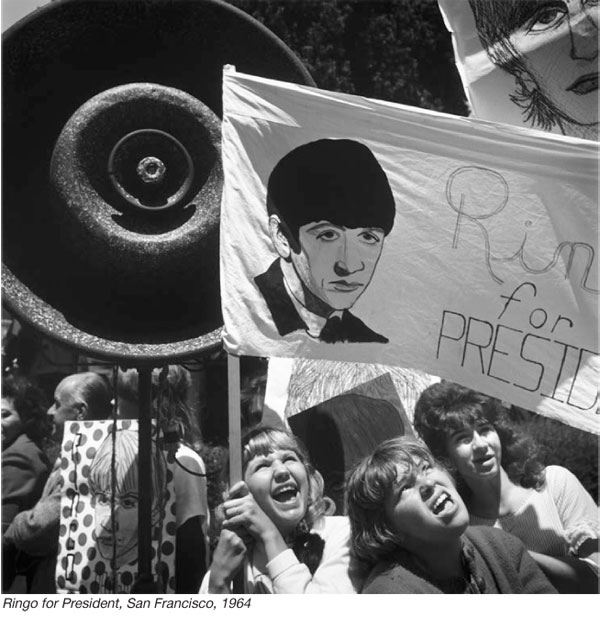

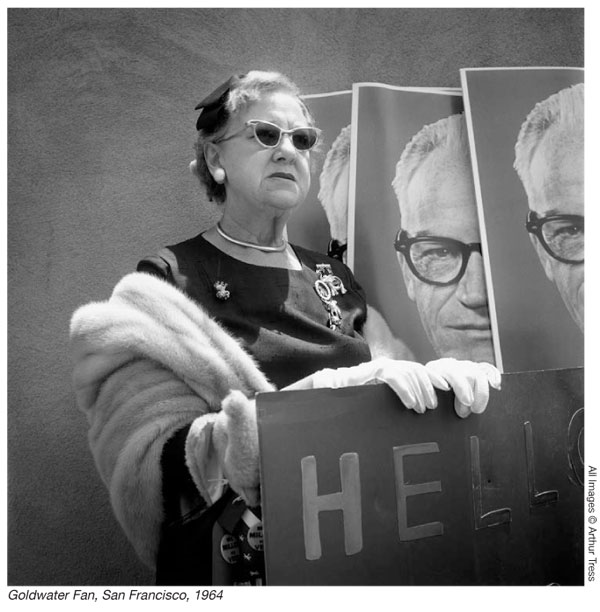

AT: In 1964 I stayed with my sister Madeleine in San Francisco and spent four or five months photographing this transitional time in the city. The Beats had left, but the Summer of Love had not yet happened.

The Beatles arrived in town on their first North American tour and the Republicans staged their National Presidential Convention that nominated conservative Senator Barry Goldwater. I rediscovered those photographs in 2009 when cleaning out my sister’s house after she passed away. I had contact sheets made of about 100 rolls of film. James A. Ganz, who was then the curator at the De Young Museum in San Francisco, went through the contacts and organized the exhibition.

RH: How do you visualize your photographs?

AT: Similarly to Henri Cartier-Bresson, who I traveled with in Japan. I organize my compositions according to geometrical planes and the interaction of shapes that relate to one another.

RH: How did you come to do your noted Dream Collector work?

AT: I began this project with Richard Lewis from Bard College, who still runs the Touchstone Foundation for promoting creativity in young children. He invited me to work with him on a workshop designed to get children to make paintings and poetry from their remembered dreams. This was the perfect ingredient to coalesce my interest in derelict urban spaces and ethnographical photography involving rituals and ceremonies. I asked children about their dreams, conducted research on dreams, took dream therapy, asked adults about their dreams and what they remembered about their childhood dreams. Then I would make long lists of dream themes, like flying and falling, and this led me to start doing staged photography.

RH: How do you define your way of working?

AT: What I really do is improvise out of reality. I create a thought matrix in my mind based on these themes in my head, like being chased by monsters, and allow the real world to produce the kind of things I am thinking about. For example, Flood Dream (1970) resulted from photographing kids playing on the roof of a house sitting around a pier. I asked one to put his head through the roof, which was firmly on the ground. It is not as if I am setting this whole thing up. Rather, I magically pull all these ingredients together and it comes together into a Tress photograph.

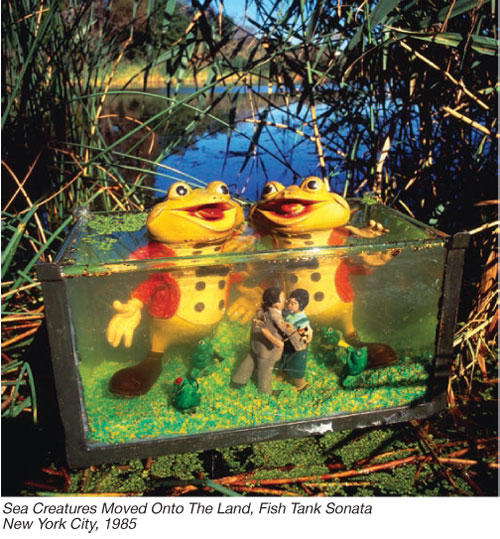

RH: Why did you switch from B&W to color?

AT: I had been photographing people in B&W for 30 years, but around 1979 I began making still lifes, which I then started setting up on an old toy children’s theater stage. I photographed these scenes in B&W for a year before realizing they would look much better in color. This became Teapot Opera (1985), which was my first color book. I continued that with Fish Tank Sonata (1986), taking the objects out into nature. The third part is Requiem for Paperweight (1988), which was done in the manner of tabletop photography. I also did a color project called Hospital (1987) in which I worked in an abandoned hospital and painted the abandoned objects that had been left behind. The color just exploded inside me.

RH: Tell me about your photo-based paper sculptures?

AT: I began making these complicated photograph collages by shooting though a crystal ball. I would take the resulting prints, cut them up, and make them into collages. I started looking at children’s pop-up books and I taught myself paper engineering. I got very good at making complicated three-dimensional photographic pop-ups, which were at exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.

RH: What have you learned about photography?

AT: I no longer see any difference between a staged photograph, a directed photograph, a conceptual photograph or a documentary photograph. They are all projections of the photographer’s imagination.

RH: What qualities makes one a good imagemaker?

AT: You must have that urge to make pictures and seeing life as a process involving transformative imag- ination that you participate in. Make specific bodies of work. Realize you will probably be poor, so will most likely have to have a day job. My approach has been one of making myself freer by not being afraid to transform myself. I regularly reinvent myself when I find my work becoming repetitive and move onto something new. This explains the diversity of my practice, but looking over it seems to still be all one piece.

I allow myself to fail without feeling guilty. If I always look for success then I will be limited in what I can explore. I try many different projects and various approaches. Some are very fertile and some dry up, but I just keep going.

Editor’s Note: More work from Arthur Tress can be found at arthurtress.com.

![]()