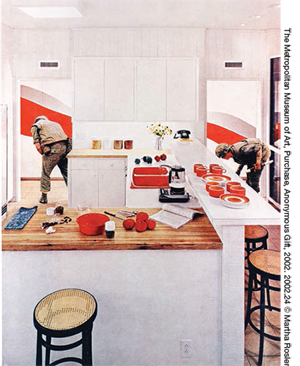

MIA FINEMAN Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop

Although digital imaging has raised society’s awareness about how camera images are constructed, the practice of hand altering photographs has existed since the medium was invented. Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop is the first major exhibition devoted to the history of how photographers have actively interacted with pictures before the digital age. Following the curatorial premise that “there is no such thing as an absolutely unmanipulated photograph,” the project offers a stimulating view on the history of photography as it traces the medium’s link to visual truth by concentrating on how images were changed after the camera capture. It does this by featuring some 200 photographs created between the 1840s and 1990s in the service of art, commerce, entertainment, news and politics. The show and catalog were organized and written by Mia Fineman, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photographs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. She earned her PhD from Yale and has worked at the Met since 1997 on a range of exhibitions. What follows is a condensation of recent conversations between Fineman and Hirsch.

Robert Hirsch: How did you get involved with this subject?

Mia Fineman: The idea for the project came out of a question that I found people asking at photography presentations: How has digital technology changed photography? Specifically, has the ability to easily manipulate photographic imagery changed photography’s relationship to truth? My conclusion, based on three and half years of research, is that things have not changed as much as most people think. The exhibition is a history of pre-digital manipulation that demonstrates that nearly everything people now associate with digitally manipulated photography has been part of the medium’s history from the beginning.

RH: How did the project get its title?

MF: “Faking It” seemed catchy enough to attract the attention of a wide audience; even though fakery is only part of the story. And I wanted to include “Photoshop” in the title because it has become the common shorthand for “digital image manipulation.”

RH: What was your definition of a manipulated photograph?

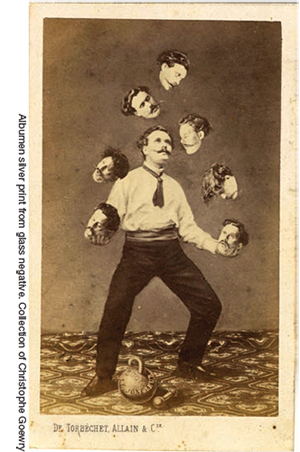

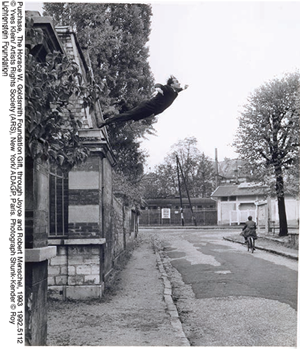

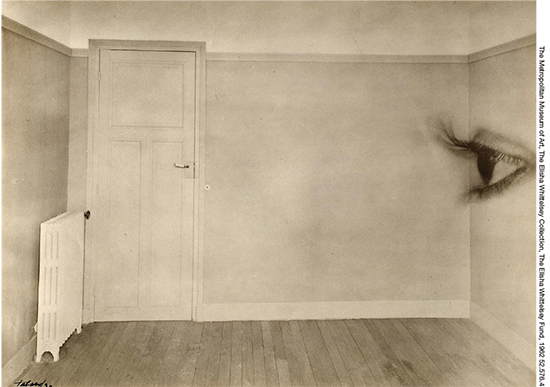

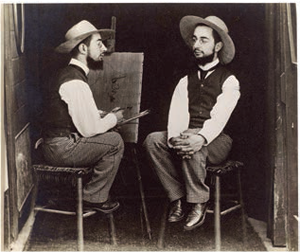

MF: As I wanted to trace the prehistory of Photoshop, I limited my selection to photographs in which the image captured by the camera had been significantly altered in post-production. In every case, the final image differs decisively from what stood before the camera at any given moment. Also, I only included photographs that look like photographs—pictures that speak in the language of photographic realism and were not overtly manipulated in a way that calls attention to their hand-work. There are a few examples of staged or setup photography, but in each case, the original camera image was manipulated in other ways as well, such as combination printing, photomontage, or retouching.

RH: How did you determine what to include?

MF: I visited collections around the world to find the most historically and aesthetically significant examples dating back to the beginning of photography. I divided the images into categories as my research evolved and as I figured out how this history unfolded. I had about three years to work on it and I could have kept going — my only real limitation was time.

RH: How have people’s notions about photographic truth evolved?

MF: When photography was invented in 1839, people were captivated by the idea that photographs were direct imprints of nature created by the sun. Photographs answered a need for objective representation that was not being met by pictures created by hand. This quickly changed. By the late nineteenth century people had become more skeptical and more interested in staged or manipulated photographs that blurred the line be- tween truth and fiction. With the rise of photojournalism and documentary and straight photography in the early twentieth century, there was a renewed desire for objective truth in photography. Although people were certainly aware of manipulation in advertisements and Hollywood glamour shots, the ideal of photographic truth dominated most of the twentieth century. This attitude began to change in the early 1980’s with the rise of Postmodernism and the beginning of digital manipulation. Once again people started looking at photographic images as partly fictional. Basically there has been an oscillating pattern between belief and skepticism throughout the medium’s history.

RH: Why has this way of working not received wider recognition?

MF: In earlier histories of the medium, such as Beaumont Newhall’s History of Photography from 1939 to the Present Day, manipulated images were either neglected or treated as eccentric deviations from the mainstream of “pure” photographic practice epitom- ized in the work of Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand and Walker Evans. It is only recently, due to an increased awareness and embrace of manipulated photography, that curators and historians have begun to delve into this other, parallel tradition, which includes artists like Henry Peach Robinson, Oscar Gustave Rejlander, William Mortensen, Yves Klein, Duane Michals, Jerry Uelsmann and many others.

RH: What did you discover that was surprising?

MF: I was surprised to discover photographers who were well known in their day who are practically un- known today. For example, William Notman (1826– 1891), a portrait photographer who operated 24 studios in Canada and New England. He made complex, large- scale composite group portraits and yet is rarely mentioned in most histories of photography.

RH: What conclusion did you reach?

MF: The show is divided into seven sections, each of which focuses on a common and significant motivation for manipulating the image. A key motivation in the nineteenth century was the desire to compensate for photography’s perceived limitations. This included ad- ding color because the prints were monochrome and using combination printing to add clouds to landscape photographs because skies were often overexposed. By the 1850’s people were manipulating photographs for artistic reasons: to exert more control over the medium and to imitate other art forms like painting and printmaking. Photographs were manipulated for political reasons in various types of propaganda, and newspapers used various darkroom procedures to cre- ate images of events at which no photographer was present. Artists in the early twentieth century manipulated photographs to invoke internal, dreamlike states and imaginary worlds, while more contemporary artists altered their images to call attention to the malleability of photography itself.

RH: How has digital imaging affected photographic manipulation?

MF: The technology for altering photographs has become much faster, more accessible, and more precise. Although the tools have changed, the desire and motivations for manipulating photographs have largely remained the same.

RH: Have you noticed differences in how photo- graphers use analog and digital tools?

MF: Not really. Mostly I found many similarities. In terms of content, I actually haven’t seen much done with digital technology that had not been done previously. At least not yet…

The exhibition was shown at the Met from October 2012 – January 2013 and will travel to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (February 17 – May 5, 2013) and then to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (June 2 – August 25, 2013). Further details can be found at metmuseum.org.

![]()