The World in Color The World in Color

Afterimage V. 35 No. 4, p. 28.

Review by Robert Hirsch

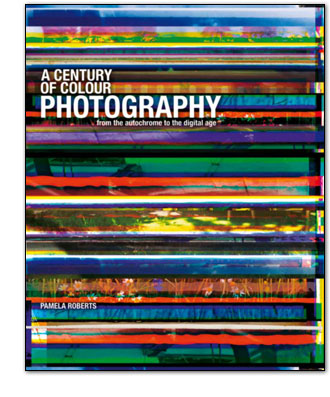

A Century of Colour Photography: from the autochrome to the digital age

By Pamela Roberts

London: Andre Deutsch ltd, Carlton Publishing Group, 2007

256 pp./$39.00 (hb)

Marking the centennial of the commercial introduction of the Lumière brothers’ autochrome process in 1907, Pamela Roberts, former Curator at the Royal Photographic Society from 1982 to 2001, has written a much-needed introduction to the underserved history of color photography. A Century of Colour Photography: From the Autochrome to the Digital Age presents the major technical and artistic happenings of the field over the past one-hundred years plus a brief chapter about its earlier developments.

The large-format pages (12-3/8 x 10-1/4 inches) feature a straightforward design with good size reproductions on glossy stock, offering unencumbered viewing of over three-hundred color plates. However, the overall production values convey an atmosphere of advertising rather than one of a scholarly endeavor. The reproduction quality of some contemporary images, including those of Gregory Crewdson and William Wegman, appear too cool, dark, and flat, and thus lose their visual authority; and image information is not included under each plate, necessitating flipping back and forth to the index of images by photographers to locate each picture’s title, date, size, and process. Additionally, a more in-depth general index would have been useful.

Production issues aside, Roberts delivers a significant general survey of color photography by utilizing a decade-by-decade chronological approach. There is a strong chapter on autochrome and its alternatives, with coverage of Albert Kahn’s The Archives of the Planet, and the works of Leon Gimpel, Stephane Passet, and Edward Steichen, who “never stopped experimenting with colour and his autochromes, especially those of his sad-eyed daughter Mary—are amongst the most beautiful ever taken.”1 Another chapter, “The Colour Boom,” covers the role popular magazines played in stealthily interjecting the expectation of color photographs into their productions. Photographers, such as Nicholas Muray, whose “work can be terrifically kitsch in parts but also hugely confident and striking, especially his portraits of women—his lover Frida Kahlo, and Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe,” helped drive public acceptance of color photography long before it was recognized by fashionable galleries and museums.

Drawing on her years of curatorial experience, including collecting autochromes and other early experimental color work,2 Roberts’s solid picture research incorporates works from private collectors and galleries. Besides the usual suspects like Eliot Porter, Joel Meyerowitz, and Martin Parr, her scholarship allows readers to become acquainted with seldom seen images, such as early autochromist Fred Payne Clatworthy and overlooked Kodachrome practitioners like Saul Leiter. This is vital as museum collections are often deficient in this area because of their past reluctance to collect color images due to archival concerns or their underestimation of color’s artistic importance.

Roberts’s emphasis on previsualization, how the camera sees and records color, results in a lack of coverage of the postvisualization movements, how what the camera captures is just a starting point for creative production. Although there are examples by anonymous photographers, the snapshot genre, especially the 1963 Kodak Instamatic that played a vital role in making color photography ubiquitous, is given scant coverage.

Roberts does bring into view underserved women photographers, such as Madame Yevonde,3 a British color portrait and advertising photographer from the 1930s who favored the British Vivex tricolor carbro process to create a body of fantastical Surrealist-inspired work. Roberts notes, “She has inspired others including Cindy Sherman and now Jesse Landberg, a New York based filmmaker who is producing a feature film on her for 2008.” Other women involved in early color photography, such as Sarah Angelina Acland, Violet Blaiklock, Gisele Freund, Helen Messinger Murdoch, and Agnes B. Warburg, are also represented.

Human color perception is a highly subjective and dynamically changeable process. This is reflected in Roberts’s own favorite curatorial choices including John Batho for his “pure colour and form” and the later Paul Outerbridge Mexican material for its “extraordinary colour balance—so pure, lively, and intense. I discovered quite a lot about my own colour awareness whilst researching this book. Red was always my preferred colour but now I seem to be obsessed by shades of green—perhaps it’s an age thing?”

Roberts’s project was not intended as a technical treatise. This ground has been covered first by E.J. Wall, then Joseph S. Friedman, and more recently by the late Brian Coe and Jack H. Coote. Rather, Roberts puts forward an aesthetic history of color photography that knowledgeably introduces key events, such as William Eggleston’s 1976 Museum of Modern Art exhibition that helped usher color photography into the art world. Additional detailed coverage of such events would have been welcome, especially in how societal changes steered color photography in new directions.

Ultimately, Roberts supplies a much-needed entry point for people desiring an overview of western color practice that is clearly written without pretense or academic jargon. Roberts’s book, completed in only nine months, will perhaps inspire other historians and publishers to delve more deeply into this neglected subject.

RH

NOTES 1. All quotations by Pam Roberts are from emails with the author and a meeting in Rochester, New York, on October 11, 2007. 2. Through Roberts’s efforts, the National Media Museum in Bradford, UK, the current home of the former RPS collection, has one of the world’s finest public autochrome collections. 3.

|