|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Keith Carter: Transcendental Realist

Photo Technique S/O 2013

By Robert Hirsch

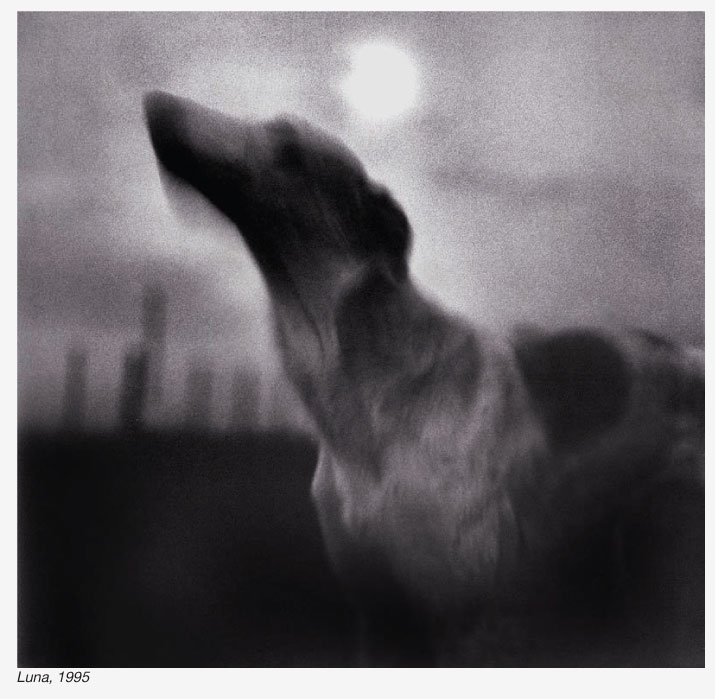

Keith Carter has been called a transcendental realist for his hauntingly enigmatic and mythological toned photographs that blend the animal world, popular culture, Southern folklore and religion from his East Texas home. Carter has published over a dozen monographs and teaches photography at Lamar University where he holds the Endowed Walles Chair of Visual and Performing Arts. The following represents a condensation of our recent exchanges.

Robert Hirsch: How has your background affected your imagemaking?

Keith Carter: I’m a self-taught photographer from a Southern culture on the Texas-Louisiana border. My mom was a single parent who made a living as a pho- tographer of children and families in Beaumont, TX. A sculptor in town, David Cargill, became my mentor and we still have lunch every Wednesday. David had a darkroom and an art library that had a profound influ- ence on me. It was the beginning of my art education and the awakening of my aesthetic. Cargill taught me the importance of craft and to be ruthless with the use of visual space. He would say, “If it doesn’t balance something or say something, get it out of there.” His words haunt me to this day.

RH: How did you learn black and white photographic craft?

KC: I was electrified from the first time I saw a good print, particularly by the way it rendered light. I learned to print in my converted kitchen darkroom from The Ansel Adams Photography Series and David’s help. He encouraged me to experiment, which is how I discovered that I could put toners on top of toners. I hesitate to use the word love, but I am going

to use it here. I love black and white photography because it puts everything on the same democratic plan- et for me.

RH: What lead you to tone your prints?

KC: I was overwhelmed the first time I saw Paul Strand’s magnificent dark, brooding and purplish prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art back in the 1970s. Strand’s gold chloride toning methods evoked atmosphere and emotion in me and demon- strated the possibilities of the creative use of photographic chemistry.

RH: What role does focus play in your work?

KC: Focus plays a large role. I have a great appreciation for photography’s early days when the materialswere slow and photographs had short depth of field. For me it was about what you couldn’t see and what was left to your imagination. I began using slower speed films and shortening my depth of field to call attention to innocuous and subtle things within the frame. I was teaching a large format camera course and my students were not properly operating the camera’s swings and tilts, but I liked their results so much I started doing it wrong too. I also use a Hasselblad Flexbody with a 80mm lens because there isn’t a large spatial or perspective change, it sees much like my eyes see.

RH: How did you to develop your artistic syntax?

KC: I come out of a documentary tradition, but after awhile I wanted to put my own stamp on things. It became clear to me that the subject matter I really cared about had to do with a sense of place, of geography, of the animal world, of the spiritual world and the elements of theology and folklore.

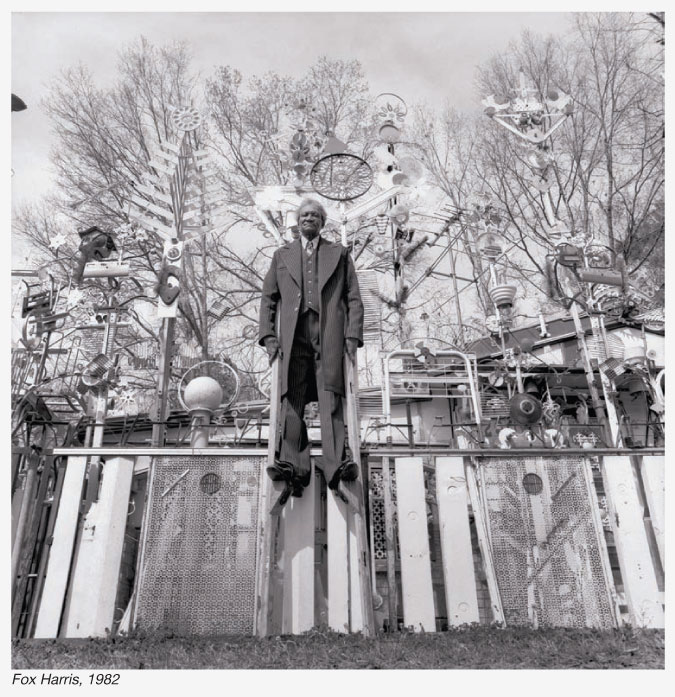

RH: How did African American Art and Folklore along with Southern literature affect your direction?

KC: They made me realize that art could be made anywhere and out of just about anything. Another of my unwitting mentors was an older black man named Fox Harris. He was a folk artist whose yard had totems in every square foot that reached to the heavens. He made things for both practical and ethereal reasons instead of the “me-me-me” thing that many of us do. He was doing it for no one but himself. I also started reading Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Conner and William Faulkner. Early on I had pored over Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) and realized it was James Agee’s prose, not Walker Evans photographs, that devastated me. I also got interested in African American folklore and legends. This was a wonderful period of personal evolution and realization about what makes the South a distinctive region and resulted in a book called Mojo (1995).

RH: How did your series Imagining Paradise come into being?

KC: It came about as a way to explore the changing oddities of my own ocular vision and was a response to a couple of things. One was a quote I have on my darkroom wall by the surrealist writer Jorge Luis Borges, who became blind in his late fifties. He said, “I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.” At the time, I had lost most of the vision in my left eye, but I could still focus and print. When I closed my good eye my vision was dirty and mottled. I began to think that my idea of paradise was the beauty and joy of seeing. This, in a roundabout way, took me into the wet-plate collodion world and changed my relationship to the emulsion side of the negative.

RH: How has your physical interaction with your negatives affected your images?

KC: The physicality was startling. The history of photography evolved from a system of markings but when I was doing this work I was thinking about Japanese ink and calligraphy drawings. I started making marks on a 21⁄4 inch negative, which I would enlarge to 20x20 inches. The marks would take on iconographic meanings in ways I couldn’t articulate. They were satisfying to do and they lead me to want to take it further, to try and destroy what had always been precious to me, the negative, with the hope of bringing forth something new. The wet-plate collodion process is a different animal. You are essentially making film and it can be hard to control, which is both wonderful and frustrating. Every picture you make is like Christmas−a real surprise. In my current project, Shangri-La, I am making 8x10-inch collodion tintypes exploring a piece of land near where I live that has been turned into an eco garden, but is mostly swamps. It is a slow, laborious and fascinating process. I get so excited sometimes looking at the ground glass that I forget I can’t see all that well, which is pretty great.

RH: What role does beauty play in your work?

KC: The whole beauty issue is a twisted contradic- tion to me. In the current art world there is almost a beauty phobia. The irony is that the search for purpose and beauty in people’s lives is just huge. On the other hand, my idea of beauty is often a bit skewed or dark. Consider the French artist JR who pasted giant portraits of women who lost children to violence on the favelas [shanty towns] in Rio de Janeiro. They are haunting, issue-oriented, and beautiful all at the same time.

RH: What role have photographic books played in your work?

KC: I’m of the generation who considered books to be photography’s Holy Grail. I learned from them and I wanted to make one. I think of my books as small auteur films in which I write the screenplay, do the photography, and the editing. It took me 18 years to publish my first book From Uncertain to Blue (1988). With today’s digital technology I now teach students to self-publish their own books in a few weeks!

RH: What qualities make a good imagemaker?

KC: I think it’s helpful to have an understanding of the history of your medium, perseverance, imagination, a good work ethic, a celebratory or thoughtful outlook on life and to learn to live in the world as it is. In terms of the work itself, for me it’s always content first−What do you want to say, who do you want to say it to, and how are you going to say it? They’re simple questions, but a lot of people don’t bother to answer them.

RH: What has photography taught you?

KC: When I have a camera in my hand I experience a heightened awareness and pay closer attention to what is around me. Photography has helped me find a way to explore the sometimes-wild spiritual dimension in my own life. It has led me to mine an intersection where a Darwinian wonderland meets American magical realism. It’s a beautiful world out there that warrants re-investigation, and photography has helped me participate intimately in it.

Editor’s note: To learn more about Keith Carter’s work visit: keithcarterphotographs.com

Robert Hirsch's latest book is Light and Lens: Photography in the Digital Age. Also, new editions of Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Equipment, Ideas, Materials, and Processes and Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography have just been released. His recent installation, World in a Jar: War & Trauma, has been touring internationally. For more information about his written and visual projects see www.lightresearch.net.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|