Brian Ulrich's Copia: A Tale of American Plenty

Photo Technique

July/August 2013

By Robert Hirsch

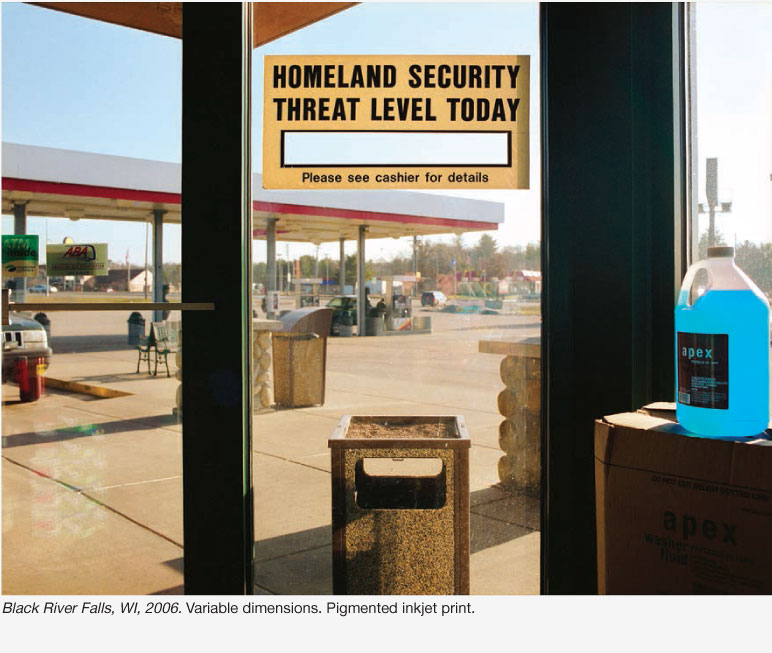

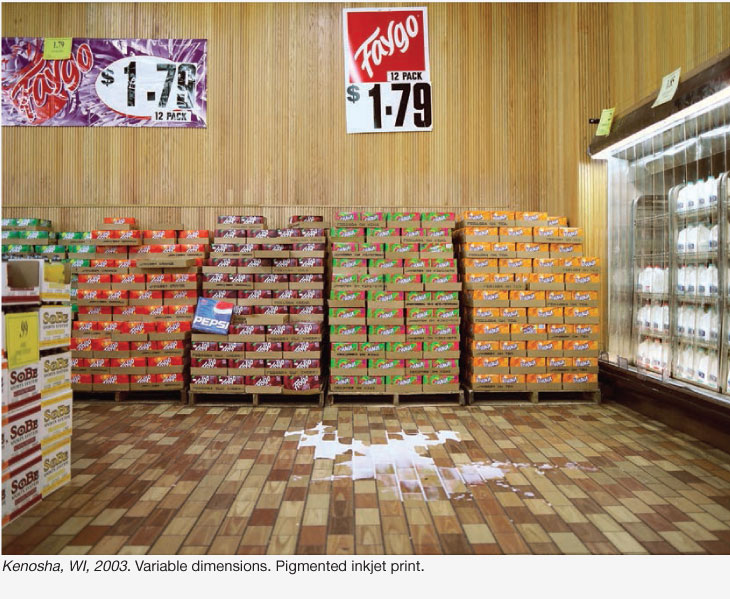

After the attacks of 9/11, President Bush encouraged Americans to go shopping, equating consumerism with patriotism. Brian Ulrich’s Copia was a response to that advice, “a long-term photographic examination of the peculiarities and complexities of the consumer-dominated culture in which we live. Through large-scale photographs taken within both the big-box retail stores and the thrift shops that house our recycled goods, Copia explores not only the everyday activities of shopping, but the economic, cultural, political and social implications of commercialism and the roles we play in over-consumption and as targets of advertising.” Copia unfolds in three acts, each representing a facet of American financial life. Retail focuses on the middle class, Thrift examines the secondary life cycle

of consumer goods, and Dark Stores reveal the results of the recession.

Robert Hirsch: What is Copia’s connection to Robert Frank’s The Americans?

Brian Ulrich: One of the great themes of Frank’s book is the manufacturing of desire in American culture. This desire is directly connected to capitalism, it becomes a cultural identity so entrenched so that any threat to it is regarded as catastrophe. This is the umbrella cloud that Frank is photographing in. I was curious what is different, what remains the same and how this defines who we are now.

Within the war speak of 2001 and 2002 there was a notion that we could protect our economy by shopping. It became clear how this idea of the American consumer having the capital and leisure time to spend on things was connected to our economic and psychological well being, which goes back to Frank.

I had at one point a copy of The Americans that I used as a sketchbook. I made specific correlations and taped in my own pictures over his to see if there were relationships between content and concept would match my pictures. It was an interesting exercise and helped expand what the work could be.

RH: What different stances have you taken in each series?

BU: In Retail I used a medium format camera with a waist level viewfinder. I scouted a location and waited for something to happen, photographing candidly. The pictures could allow you to stare in situations where you are not allowed to stare. In Thrift I started using a 4x5-inch camera. This allowed me to slowly set things up and imply candid or psychological portraits of the people that were working at these places. In Retail, I wanted to reinforce the homogenization of culture by photographing the same brand stores across the country. In this sense, my subject was everywhere. I love the relationship between figure and architecture and the figure and content because it is simultaneously contemporary and historical.

RH: How has Copia affected your own personal habits?

BU: What is interesting is we live in an environment that presents an illusion of choice that is extremely limited and does not fulfill our needs and wants and desires. In some cases it doesn’t allow us to make good choices. That is by design and not by accident. Once I started to understand that, that became a really interesting relationship to buying and owning things. I began thinking about what was at play there and whom am I supporting and where does the money go. Part of the equation is our relationship to China and the mass production of American consumer goods that began by design in the 1980’s and has sped up so much that now there is a tug-of-war stage, which is fascinating.

All these things are connected and wrapped up into our psyche and literally have direct effect on people’s lives. You see these effects on what opportunities people have, what they become, their well being, their happiness or whether or not someone would want to have children. You see it. It is all there.

RH: What did you come to understand from Dark Stores?

BU: I worked on Dark Stores from 2008 to 2011. I wanted to make them overly dramatic and cinematic. Photographing them at night with an 8x10-inch view camera really helped. I started using flashlights and the exposures were really long, sometimes up to an hour. The photographs are indictments. They represent the policies of the banking industry and how communities are so dependent on tax revenue and em- ployment that they will open their doors to whomever comes their way and build a place without regard to the consequences. When these places close the doors the communities are left with blight and debt, producing large economic problems in our cities.

RH: What have you learned from this decade of work?

BU: A tremendous amount. You learn all the time. You learn from your practice and the reception to the work. I would say that one of the biggest things I came to appreciate is complexity of the photographic language. Photography acts as this simple mechanical tool, a transcription of three-dimensional material into a two material by means of light. Yet, the things that happen during the process of making are very complex. When I started photographing with the 8x10- inch view camera, I realized how much that camera exaggerates the phenomenon of making photograph. Literally every aspect of making a picture with it is completely amplified, such as the framing and depth of field. This helped develop a deeper understanding of how optical fidelity renders a relationship to the knowledge of subject.

RH: What qualities are necessary to be a good photographer?

BU: This project has taught me to be patient, place an emphasis on curiosity, investigation, and research and to welcome failure. Some things might not amount to anything, but they will make you smarter about the thing you are interested in. It makes you smarter about making pictures and smarter about the subject. So the failures are not failures. They are the lessons of making the work. I do not try to make a bad picture but I am not disappointed if it has not done what I wanted it to do. I take that as the time to learn from it and adjust.

Let the work tell you what to do and where to go. Let it point you in a direction. That comes from being pa- tient and resolute and extremely stubborn. Pay a lot of attention to what you are looking at as well as the transcription of it into the photograph.

Ulrich was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2009 and currently teaches photography at Virginia Commonwealth University. His photographs have been published in The New York Times, Mother Jones, and Orion, among others. A monograph of his work, Is This Place Great or What? (2011), is available.

His work has recently been exhibited at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Anderson Gallery, Richmond, VA. Upcoming shows include the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC and the Haggerty Museum of Art, Milwaukee, WI. See more of his work at: notifbutwhen.com

Robert Hirsch is author of Light and Lens: Photography in the Digital Age, Exploring Color Photography: From Film to Pixels; Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Equipment, Ideas, Materials and Processes; and Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography. Hirsch directs Light Research, a consulting service that provides professional services to the fields of photographic art and education. For details about his visual and written projects visit: lightresearch.net. Article ©Robert Hirsch 2013.

|