Brian Taylor and the Photographic Narrative

Photo Technique

May/June 2013

By Robert Hirsch

Brian Taylor innovatively explores alternative processes in- cluding historic nineteenth century printing techniques, mixed media and handmade books. Taylor is a Professor of Art in the photography program at San Jose State University where he has taught for 30 years. The following are highlights from our recent discussions.

Robert Hirsch: How would you describe your artistic voice?

Brian Taylor: My photographic practice involves visualizing the poetic interior views of my subjects and communicating these visions to others. Most photographers act as hunters in search of a preexisting scene: without a specific image in mind, they stalk the elusive “wild” photograph. In 1941, Ansel Adams didn’t plan on photographing a moonrise over the tiny town of Hernandez, New Mexico. Another approach involves premeditating a scene and conjuring up images that merge the outer appearance of a subject with our in- ternal thoughts about it.

RH: Why work in this manner?

BT: I want to photographically portray scenes from my imagination that do not exist in this world. Like most artists, I hope my visions are worthy of your time and consideration. Along with such egotism, I also keep in mind Ernest Hemingway’s idea of a “crap detector,” working hard, scrutinizing one’s art and not wasting a viewer’s time.

RH: Discuss the evolutionary arc of your work.

BT: Having studied with Oliver Gagliani, a master of large format photography and the Zone System, I have conservative roots. Ansel Adams and Minor White were my early heroes. Ansel reminded us, “Every musician must learn to play their instrument before they compose their own piece.” My strict Zone System education taught me how to play the instrument of black and white photography so I can now break the rules and improvise. Eventually, I came to realize that a traditional photographic voice was not my voice. I wanted to imbue my photographs with more of a human, handmade touch.

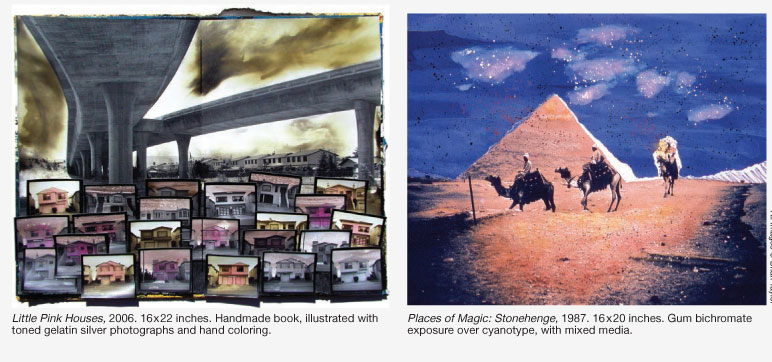

I have the highest respect for fine black and white printing, but now I commit heresy by drawing, painting and tearing photographs. I savor the tactile pleasures of making art by hand. I enjoy the organic experience of brushing non-silver photographic emul- sions directly onto textured watercolor paper. I take pleasure in the physical surface and beauty of archival 19th Century processes, for they require the artist to slow down and contemplate the image being printed.

RH: How do you define your approach to the landscape?

BT: My definition of a landscape includes everything from mountain ranges to inner city sidewalks. I am drawn to the intersection between nature and the evidence of mankind, where the outreaches of civilization begin to blend into wilderness.

RH: How did you come to make handmade books?

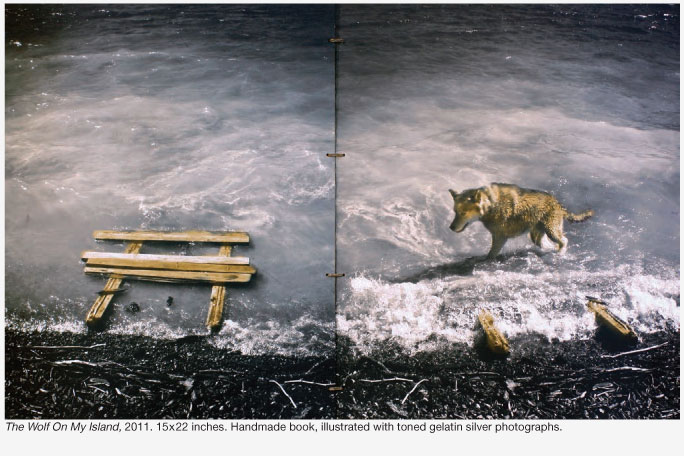

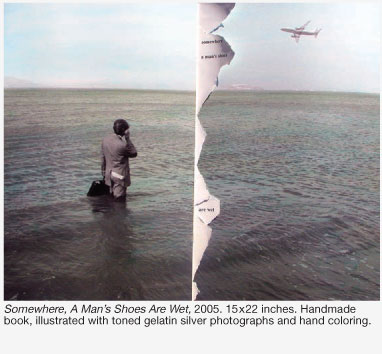

BT: I often feel that the single photograph is just not enough, that I have more to say. I started making open books in the early 1990s and continue to find it wonderfully liberating. By juxtaposing one photograph next to another, a relationship is created that is greater than the sum of its parts. Sometimes I’ll even tear pages in the gutter of my open books to include just a few words between two images, like Haiku, expanding the work’s narrative possibilities.

RH: Why is a narrative vital to your art making?

BT: Beyond the trillions of images that have been taken since the birth of photography, one can safely say everything on our planet has been photographed. Why make yet another photograph of something that already exists? What people have to offer is their narrative, their story of living in this world. I offer Brian Taylor’s (often quirky) perspective.

RH: What role does beauty play in your work?

BT: Contemporary art trends aside, it will be a sad day when beauty no longer has value in our lives. I aspire to make beautiful art because it’s the best way to engage people, to have them pause and consider your artwork no matter the content, whether it is scathing social commentary, lighthearted humor, or dealing with issues of mortality. Beauty is a measure of per- fection. It lets you know when all of the pieces are fitting properly. I am reminded of the old English gun makers who would pick up a finished gun, weigh it in their hands and then give their highest compliment: “It feels all of a piece.” For me beauty is when all the pieces fit together.

RH: What are the social implications of your work?

BT: Some photographers, like Robert Adams, whose work examines the changing landscape of the American West, feel photography is really not a powerful medium to bring about social change. I share his view that art’s purpose is to help viewers get to YES. This is the recognition there can be hope in art, which can serve as an affirmation that helps people reengage with the world. Such a reengagement may well improve our society.

RH: What is different between analog and digital tools?

BT: I live in San Jose, California (Silicon Valley) and years ago I was asked to beta test a new software program called Photoshop. This lead me to realize that making digital photographs meant sitting in front of a monitor pushing pixels around a screen, while traditional photography has you standing up, interacting with the world more, moving around a darkroom. Each of us is free to decide how we want to work and choose the medium that feels right.

RH: How has digital imaging affected your role as a photo educator?

BT: For today’s students, it is a 100 percent digital world and we owe them a relevant education. And yet, there appears to be a “rediscovery” of film and silver prints among many young photographers. They feel a greater sense of achievement in claiming their hand touched and created the image in a now exotic darkroom−it feels more of an accomplishment than tapping Control P on a keyboard.

RH: What have you learned about photography? BT: Susan Sontag posited that photography gets between an experience and us. For me it is the opposite. In the chaos of our over stimulated lives, photography allows me a deeper connection with the world; I never look so closely as when I have a camera with me. One of my artistic ambitions is to organize this turmoil and crystalize it into a narrative that makes sense of our human condition.

RH: What makes someone a good picture maker?

BT: Visually, we should remain an open vessel and work against how our brains filter out much of what we encounter. I tell my students they should go home thoroughly exhausted from keeping their eyes open for photographic possibilities. Look at lots of photographs. Go to galleries and museums and scrutinize work so closely that guards yell at you. Read poetry to learn how to express your ideas in an economic way.

Give yourself permission to explore anything in your art. Do not criticize yourself or your art too soon, but once you have made the work subject it to rigorous scrutiny before sending it out in the world. Form a salon group with your friends. I am part of a group that meets once a month and we give each other wonderful feedback. You will always get differing opinions, however in the end the most important thing is to trust yourself.

Editor’s Note: You can see more of Brian Taylor’s work at briantaylorphotography.com

Robert Hirsch is author of Light and Lens: Photography in the Digital Age, Exploring Color Photography: From Film to Pixels; Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Equipment, Ideas, Materials and Processes; and Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography. Hirsch directs Light Research, a consulting service that provides professional services to the fields of photographic art and education. For details about his visual and written projects visit: lightresearch.net. Article ©Robert Hirsch 2013.

|