|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maker of Photographs: Jerry Uelsmann

Interview by Robert Hirsch

This piece is the result of numerous conversations, emails, letters, and photographs between September 2001 and February 2002.

Making Photographs

Robert Hirsch Your work is synonymous with “post-visualization,” that is a negative is only a starting place for a photographic image. How did this concept evolve? Robert Hirsch Your work is synonymous with “post-visualization,” that is a negative is only a starting place for a photographic image. How did this concept evolve?

Jerry Uelsmann During the early 1960s I was the only photographer in an art department at the University of Florida at Gainesville. I worked with painters and sculptors who were interacting with their art as it was being created. That’s when the post-visualization idea occurred; that the darkroom could serve as a visual research lab. I spend much time in my darkroom building images from separate negatives, hopefully into something cohesive. My main technique involves combination printing. I did not invent this method; it was widely used by Oscar Rejlander and Henry Peach Robinson in the 1850s. When I began re-investigating darkroom options I was reminded of the saying that “nothing is new except what has been forgotten.”

RH How does your view of the darkroom affect your image making?

JU It is the same as a painter going to the studio. I have made the darkroom to be comfortable in order to spend long periods of time in there conducting my experiments. My big technical revelation in multiple printing occurred while I was waiting in the university darkroom for prints to wash and was staring at all the enlargers. Suddenly I gave myself a slap and thought “Oh, my God, if I put my negatives in different enlargers I could move the paper from easel to easel rather than constantly switching the negatives in the enlarger.” By breaking free of the mental formula that taught me to use a single enlarger rather than a battery of enlargers, I was able to vastly increase my explorations and options.

RH Why is the act of photographing vital to your creative process?

JU The camera is a license to explore. It grants you societal permission to go out and interact with the world. It gives value to my life. Even if I did not have the finished images that I made, I still would be content with all the experiences that the photographing has given me.

RH How has the acceptance of your work changed since the 1960s? RH How has the acceptance of your work changed since the 1960s?

JU When I began my experiments Rejlander and Robinson were not highly regarded by the small photographic community. Historians considered combination printing a misstep in photography’s quest to be recognized as an independent art form. Photographs were supposed to reflect the modernistic approach typified by Paul Strand and Edward Weston. People constantly would respond to my work by saying ‘that’s interesting but it isn’t photography.’ I bought everything I used at a camera store and spent long hours in the darkroom, so what was I supposed to call my work? I found it exciting to challenge the limits, but others found it offensive because once you begin to alter the imagery, you are treading on the societal boundaries between perceived fact and fiction.

RH How do you contend with the borderline of fact and fiction?

JU Although photographers must contend with implied veracity they are always inventing other realities. The “straight” photograph does not literally replicate a scene. An Ansel Adams picture of Yosemite is not what you experience when you go there. There is always a transition that breaks from reality. Photographic veracity is an effective tool because it implies a real situation and allows the viewer to respond to it accordingly.

The Role of Art

RH What role can an artist play in our society today?

JU I believe imagination is the primary currency of the artist. Artists come up with visions that open the world to other possibilities. Art should not be a competitive sport; artists need the freedom to explore and to risk failure. They should not be locked into one mode of thought.

RH How can art convey meaning?

JU Art is in a weak position in terms of communicating exact ideas because there is not a common iconography or syntax that transmits a specific meaning. I like the idea that there are layers of meaning that people bring to the visual experience. The Twentieth Century shifted the responsibility onto the audience to use their own inventive consciousness and experiences to react and resolve what they are getting from art. JU Art is in a weak position in terms of communicating exact ideas because there is not a common iconography or syntax that transmits a specific meaning. I like the idea that there are layers of meaning that people bring to the visual experience. The Twentieth Century shifted the responsibility onto the audience to use their own inventive consciousness and experiences to react and resolve what they are getting from art.

RH What visual imagery influenced your artistic development?

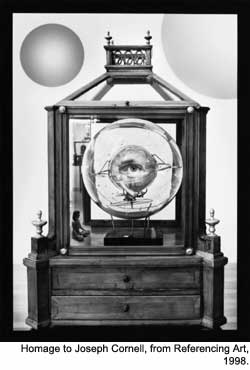

JU I was intrigued by Max Ernst and Joseph Cornell because their work used fantasy to challenge accepted ideas of reality. I collect folk art because I relate to the need people feel to create it and it is almost always emotionally based. I like images with human references and narrative strategies as I find people usually sense a greater connection with them.

RH Does spirituality enter into your work?

JU I see my photography as a spiritual activity. I work on a regular basis and there is a sense of ritual involved. It is a personal quest that permits me to challenge accepted ways of seeing our world.

RH How does this help us know our world?

JU All knowledge is self-reflective. You change, grow, and struggle to find the words and the images, but knowledge passes through who you are and your experience. Our society is ceaselessly exploring, explaining, examining, and questioning. Education should be a question raising process.

RH Have people found it hard to discuss the non-technical aspects of your work?

JU Yes, it is often difficult for people to discuss art that is emotional, psychological, or spiritually based because the critical language is not as accessible. When you evaluate art on the basis of a defined critical theory, it either makes it or it doesn’t.

Teaching

RH Do you think art can be taught? RH Do you think art can be taught?

JU I find value in teaching photography as a broad-based discipline with a wide range of approaches that encourage meaningful dialog. Preaching a single way of viewing the world reminds me of intolerant fundamentalists who are threatened by other points of view.

In Some Humanistic Concerns for Photography (1971) I stated that teaching photography in an art department could help people develop their visual awareness and sensitivity. Just the act of carrying a camera can heighten awareness. Teachers can deal with issues of creativity and getting people beyond the obvious to the next level. Over the years I have been blessed with some very good, inquisitive students who made me a better teacher.

RH What do you think about how photographers are trained today in art programs?

JU The best programs provide a balance between craft and content. In beginning courses I like to give open-ended assignments such as “photograph the evidence of man.” In the early courses, it is critical to have a person explore a range of approaches so that they may find one that has personal relevance. With more advanced students I would ask them to find work that they loved and work they disliked and have them explain their selections. Often they learned more from the work they did not care for because it challenged what they thought a photograph could be.

RH How is the concept of agreed upon verifiable truth and beauty now addressed?

JU When you give a problem in art, unlike in math, you do not want everyone coming back with the same answer. In art there is no one right answer. That is its truth, beauty and frustration.

RH How does the ability to discuss your work affect learning? RH How does the ability to discuss your work affect learning?

JU The work must come first, but in academia there is an obligation to formally share your concerns. It is difficult to create verbal equivalents for the visual, but you need to provide clues. Students often come to me thinking I am supposed to know more about what they are doing than they know. This is unrealistic. Every person needs to work on verbally sharing his or her artistic concerns.

RH How do you address issues of craft and content?

JU I try to balance the two, but one cannot separate craft from the content of the image. You cannot memorize the dictionary and suddenly start saying profound things. Building your technical vocabulary allows the depth of your work to increase and evolve.

RH What do you think about the critique as a cornerstone of teaching in an art department?

JU I do not like the term critique because it has a foreboding quality to it. I like the idea of people sharing their work. Students have a unique opportunity to hear what other people think, hopefully from people they respect, responding honestly to their work. Students need a supportive environment where they can have a dialogue, raise questions, sort out issues, and explore doubt.

Many have good ideas, but they do not know how to sustain them. They need someone to point out when they are pursuing a worthy activity. I also like students to show work in progress. Regular dialogue is effective in drawing people out, making use of the group’s resources, allowing people to keep up with current practices and theories, and expanding the discussion into other realms.

RH What do today’s aspiring image makers need to know?

JU With all the information that is now available there is an intense need for young people to simultaneously know and understand the history of photography as they learn the craft. The primary agenda is to create an open attitude toward learning so people can realize that we are students for life. Continuing to learn is the key to growth in any field. JU With all the information that is now available there is an intense need for young people to simultaneously know and understand the history of photography as they learn the craft. The primary agenda is to create an open attitude toward learning so people can realize that we are students for life. Continuing to learn is the key to growth in any field.

Life as an Artist

RH What separates an artist from a crafts person?

JU I have great respect for craft and technique. Some people get fascinated with the craft itself and become unwilling or insecure to risk trying anything different. They may get a sense of security from adhering to a prescribed path. You cannot just go and make great art. You begin with whatever ideas you have and then push them to get into areas where there is some self-doubt and uncertainty and see what happens. Often good art comes from the fringes by those taking visual risks.

RH What qualities make a good artist?

JU The one no one likes to hear is the work ethic. You cannot wait for inspiration; one has to work at being a good artist. When I started teaching I had one day a week to use the darkroom and I would work on that day whether I felt like it or not. Some days I did not feel great about it, and produced images that lasted and some days I felt great and produced images that did not survive.

RH How do you work at being a good artist?

JU I believe in the modernist proposition that each individual has his or her own personal vision and I work to celebrate that. That said, one must create conditions conducive for things to happen. I’ve already been in the darkroom this morning. I feel a compulsive need to do photography because it’s a way I relate to myself and to the world.

I do not have a specific agenda, but I try to amaze myself. However, the more you work the more difficult it becomes to be satisfied with things you did before. The other burden you face, if you’ve had outside success, is imitating yourself. I feel the need to constantly take chances to extend my range. I am not going to grow another head and start doing “straight” photography, but my life experiences have resulted in a greater sense of spiritual quality and other more subtle nuances as my work has matured. do not have a specific agenda, but I try to amaze myself. However, the more you work the more difficult it becomes to be satisfied with things you did before. The other burden you face, if you’ve had outside success, is imitating yourself. I feel the need to constantly take chances to extend my range. I am not going to grow another head and start doing “straight” photography, but my life experiences have resulted in a greater sense of spiritual quality and other more subtle nuances as my work has matured.

RH What is a difference in recognizing the form and rhythm of your working pattern as opposed to imitating yourself?

JU Sometimes I don’t recognize it. Sometimes it is just a matter of comfort. We are conditioned with stock responses and in art you try to get away from that. Sometimes it’s like the security of a warm blanket; you subconsciously fall back on a format or way of dealing with something that you’ve dealt with before. Later, if I am matting one of these prints, I think, ‘wait a minute, this doesn’t do much for me anymore.’ On the other hand, I do not want to be too critical because I could talk myself out of everything I try.

I push the visual and technical limits to have an interesting dialog with my materials. When I first saw 8x10-inch contact prints by Weston and Adams I knew that was the kind of quality I wanted in my work. I am still caught up in the tonal scale tradition of the Group F/64. It sets a technical goal for me to work to attain. Ultimately the important thing is to make imagery with implied content that resonates with an audience.

RH What triggers the making of a good Uelsmann?

JU I like images that challenge reality and sustain their mystery for a prolonged period of time so I can continue looking at them, and I still ponder what they are about.

RH How would you describe your fundamental creative process? RH How would you describe your fundamental creative process?

JU At Indiana University Henry Holmes Smith taught me that growth often involves pain. It certainly involves confusion and tolerance for uncertainty. By working and exploring on a regular basis you increase the possibilities of things happening. I don’t believe in divine inspiration. There have been a few instances when looking at contact sheets, something has come together, but that is the exception. Usually, I find a departure point and hopefully hone it into something meaningful by exploring as many options as I can.

RH What are some of your major motifs?

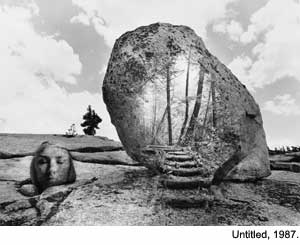

JU I have a dreamlike sensibility and believe that when we dream we invent mythic creatures and reflect different levels of reality. I am not interested in illustrating dreams, but looking for images that support a searching vision.

There is a book by John D. Barrow, Impossibility: The Limits of Science and the Science of Limits, which deals with visual paradoxes. Barrow says, ‘one of the extraordinary consequences of human consciousness is the ability to imagine the physically impossible. It lets us explore reality through the context of impossible events. This allows our creations to resonate with meaning and juxtapositions of ideas that stretch and stimulate the mind.’ This jumped off the page when I read it because I believe in this ability to invent these other realities. A psychological tension is produced when people confront these photographs that carry inherent believability and dreamlike qualities.

RH Is enigma important to you as an artist? RH Is enigma important to you as an artist?

JU Definitely. I have a predilection for imagery that has aspects of enigma and mystery because it takes me in and yet leaves me a little uncomfortable so I have to consider the situation more fully. Fredrick Sommer said, ‘If we didn’t dream, reality wouldn’t exist.’

RH What has helped you discover your direction?

JU I’ve worked with a Gestalt psychologist. I reach stages in the darkroom where I’m just at some crucial point and I don’t know what to do and I will apply a basic Gestalt technique that asks, ‘what’s the worst thing that’s going to happen? I can waste ten more sheets of paper and a couple of hours. What’s the best thing that can happen? I can astound myself.’ Thinking of that mantra causes me to push further, which is important since many of my lasting images have come from the fringes of my consciousness.

RH How would you characterize your pictorial sense of time?

JU I favor photography that has a cinematic quality and a narrative strategy. I like the notion of synchronicity and that a photograph can imply a decisive moment. In the darkroom I can often sense when an image is coming together. It’s the recognition that a synchronistic moment can occur within the process itself and not just when the camera’s shutter is clicked.

RH How do you deploy juxtaposition to create multiple meaning?

JU I like images that have a ying/yang effect. If you have one rock sitting on the table and suddenly you put a potato next to it, there is going to be a dialog that you have to figure out. It creates a context in which people can question why these things are together and how they are different.

RH How do others determine meaning in your work?

JU Interpretation is open-ended and what people see may or may not be part of my consciousness. Hopefully my work allows others to project and experience their own feelings. I like having images that are obviously symbolic, but not symbolically obvious. You just know these elements can mean something; they call upon the inventive consciousness of the viewer.

RH Have the events of September 11 affected your work?

JU Yes, but not in a literal way. The two images that I created that week were darker and not as poetic or positive. If someone knew the intimate aspects of my life, they could look back and see the relationships between my state of consciousness and the work I produced.

- Jerry Uelsmann was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1934, and received his B.F.A. degree at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1957 and his M.S. and M.F.A. at Indiana University in 1960. He began teaching photography at the University of Florida in Gainesville in 1960. He was a graduate research professor of art at the university since 1974, and is now retired from teaching. Uelsmann received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1967 and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1972. He is a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, and a founding member of The Society of Photographic Education.

Uelsmann’s work has been internationally exhibited in more than 100 individual shows over the past thirty years. His works are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Chicago Art Institute, the George Eastman House, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Bibliotheque National in Paris, the National Museum of American Art in Washington, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the National Gallery of Canada, the National Gallery of Australia, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the National Galleries of Scotland, the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, and the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto.

The following monographs on Uelsmann's work have been published:

Jerry N. Uelsmann (Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture, 1970).

Ward, John L., The Criticism of Photography as Art: The Photographs of Jerry Uelsmann (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1970).

Jerry Uelsmann: Silver Meditations (Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Morgan & Morgan, 1975).

Jerry N. Uelsmann: Photography from 1975-79 (Chicago: Columbia College, 1980).

Jerry N. Uelsmann–Twenty-five Years: A Retrospective (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1982).

Uelsmann: Process and Perception (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1985).

Uelsmann/Yosemite (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996).

Museum Studies (Tucson, AZ: Nazraeli Press, 1999).

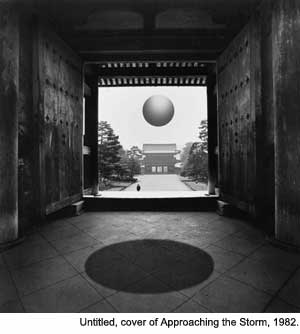

Approaching the Shadow (Tucson, AZ: Nazraeli Press, 2000). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|