|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Strange Case of Steve Kurtz:

Critical Art Ensemble and the Price of Freedom

By Robert Hirsch

From Afterimage: the Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism,

May/June 2005

(continued)

RH: How did CAE come into existence?

SK: I wish that there was a grand heroic story for the founding of CAE, but there isn’t. We were disgruntled students who decided we needed to take control of our own education and exercise some agency within the cultural environment in which we found ourselves. The formation of CAE in 1986 was simply a response to a localized problem of cultural alienation. Typical for Tallahassee, I suppose.

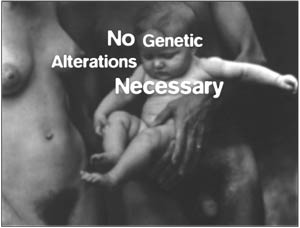

From the project "The Society for Reproductive

Anachronisms" (SRA, 1998-1999) by

Critical Art Ensemble. |

RH: What is CAE’s mission?

SK: The mission has always been very simple: To develop tactics and tools of resistance against the authoritarian tendencies of a given cultural situation.

RH: Why did you decide to work collaboratively?

SK: There are many reasons. One key reason was that we believed that cultural praxis was too complex for one person to do by him/herself. Idea generation, conceptualization, research, theorization, material production, administration, site scouting, cultural and social presentation, documentation and archive construction—it’s too much. Moreover, no one person can be good at all these things—a division of labor was necessary. We also wanted to be able to address whatever topic we felt was important at the moment and to examine it in whatever medium or combination of media we thought was the most suitable. One person can’t do all this in any kind of timely way. And finally, we were poor; we knew we had to combine resources.

RH: Who were/are CAE members?

SK: Barnes and I founded CAE in 1986. The original members also included Hope Kurtz, Dorian Burr, Claudia Bucher and George Barker. After George and Claudia left in 1988, Ricardo Dominguez and Bev Schlee joined us. Ricardo left in 1993. Dorian left in 2002.

RH: How do other CAE members support themselves?

SK: Hope was a professional editor, Dorian is a freelance photographer, Steve Barnes runs a media center at Florida State University and Bev works in a bookbindery.

RH: How does CAE decide what project to undertake?

SK: Three factors guide this process. The first is urgency. Is the issue or situation significant enough to warrant immediate attention? The second is whether the issue or situation is underrepresented. And the third is whether we find the issue or situation personally compelling. If all three factors are there, it’s likely a project is going to be done.

At Critical Art Ensemble’s project "Gen Terra"

at the London Museum of Natural History, 2003,

CAE member Steve Kurtz explains how to

use the bacteria release machine to a young participant. |

RH: Does CAE have any artistic or political agenda?

SK: CAE has no artistic agenda. We are not out to change the art world. Our political goals are for the most part tactical— achievable concrete goals that contribute to undermining authoritarian positions.

RH: Are the writings of Marx relevant to what CAE does?

SK: I don’t know if Marx is relevant to what we do. He is relevant to the left in general as he was among the first to develop the language and identify key problems. It’s impossible to understand the history and development of the left without understanding Marx.

RH: What is CAE’s outlook on Western culture and capitalism?

SK: Western culture might be OK if it wasn’t for capitalism. Capitalism is a vicious, inhuman project, and that is all it is.

RH: What would be a better model?

SK: I am afraid that no one I know of has come up with a viable utopian model yet. As I said, CAE is a tactical group, we don’t think about strategy much. We are really in no position to do so.

RH: Describe how and why CAE uses tacticality.

SK: When one is in a marginal position, there isn’t much choice about using tacticality. Without the asset of a territory to work from, strategy is off the table, and we are left only with the choice of flying under the radar, responding to specific situations. When doing tactical media we assess the situation, decide what tool is right for the job and then act. For example, we were in Adelaide, Australia, and Aboriginals wanted Victoria Square to be dual-named. The city council was sandbagging them. We suggested that we make and change the signs ourselves and not wait for the city to do it (an old, but still useful tactic). They agreed (although the process of convincing the elders was lengthy). We changed the signs.

RH: How has being a member of CAE affected your role as a teacher?

SK: I’ve learned a great deal about pedagogy from my experiences with CAE. CAE allowed me to experiment more freely with efficiently relaying information in a way that ends in empowerment and pleasure for all involved in the process. Some of what I learned could be imported back into the classroom.

RH: How has CAE affected you as an artist?

SK: I don’t think I am very invested in the term "artist," or if CAE’s work is art or not. If someone wants to view it through that lens that is fine, but it’s not necessary. I think that most of the people who aren’t from the art world who see our work never for a minute perceive it as art.

RH: How do you see the role of an artist?

SK: The term covers such a multiplicity of practices and possibilities that there is no single role.

RH: Why is New Media important?

SK: It depends on what you mean by that. If you mean as a new genre of art, it’s probably not that important. It’s just another genre—no better, no worse than any other. If you mean the apparatus through which information is exchanged, then it’s important—it’s the key mechanism for building of hyperreality (meaning constellations that are accepted as real but have no material corollary). While production is significant, the real question is who/what controls distribution.

RH: How have your written "manifestos" shaped CAE’s thinking?

SK: I would prefer to believe the thinking shaped the manifestos.

RH: What writing has influenced CAE’s writing?

SK: In terms of style, probably modern manifestos and Paul Virilio. Virilio really showed us how to stylistically use speed in presenting complex ideas. The staircase construction has been very useful this way. The day of the theoretical tome is about over except for a select portion of academia. Theory needs to be fast to be useful. In terms of ideas, the leftist canon— Marx, Peter Kroptkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Alexander Berkman, The Frankfurt School, Max Weber, Guy Debord, Michel Foucault, Felix Guattari and so on. There is another line as well such as Georges Bataille, André Breton, Jean Genet and Lautréamont.

RH: How does Virilio’s invention of the term "dromology" (the logic of speed) resonate with you?

SK: It’s not the term, it’s the philosophy. Using speed as a lens for understanding the dynamics of culture and political economy has its virtue.

RH: Are you concerned with fascist overtones due to the linkage with [Filippo Tommaso] Marinetti and Futurism?

SK: No, speed is not an inherently fascist notion or dynamic. (next page)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|