|

|

|

|

|

|

|

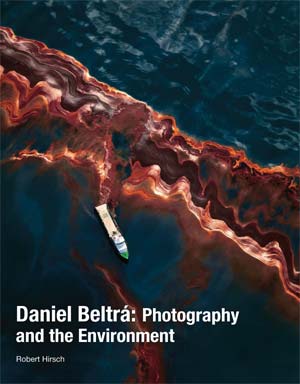

Daniel Beltrá: Photography and the Environment

Photo Technique, January/February 2012

By Robert Hirsch

|

A ship cuts through a band of oil on the surface of the water. A substantial layer of oily sediment

hes for dozens of miles in all directions from the wellhead, suggesting that a large amount of oil did not

evaporate or dissipate, but may have instead settled to the seafloor.

|

The interrelationship between photography and

America's natural environment can be traced back to

Solomon N. Carvalho's daguerreotypes made during

John C. Frémont's fifth expedition crossing the Rocky

Mountains in 1853 (only one of his plates is thought

to have survived). The expansionist notion of Manifest Destiny, public curiosity, and tall tales about the

West stimulated demand for photographic documentation of these wonders by photographers such as

Carleton E. Watkins, Timothy H. O'Sullivan, and

William Henry Jackson. In Jackson's case, his large, wet-plate photographs played a role in the establishment of Yellowstone as the country's first national

park by Congress in 1872.

As we become aware of the global consequences of

human activities, the role of increasing responsive-

ness to environmental issues is carried on by groups

such as the International League of Conservation

Photographers (ilcp.com), whose mission is to further

environmental and cultural conservation through

ethical photography.

One member of this consortium is Spanish photographer Daniel Beltrá, who now lives in Seattle, Washington. Although Beltrá began making photographs

as a teenager, he studied forestry and biology at university. In 1988, he photographed a Basque terrorist

bombing in Madrid, which lead to a job as a photographer at Spanish National Agency EFE. In 1990,

he started working with the not-for-profit, non-govern-

mental organization (NGO) Greenpeace, becoming

one of their leading freelance photographers. He has

since documented expeditions to the Amazon, the

Arctic, the Southern Oceans, and the Patagonian Ice

Fields. In 2010, he spent two months covering the

5-million-barrel oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Recently, I spoke to him about his experiences and

the following are edited excerpts.

Robert Hirsch: How did conservation become your

visual passion?

Daniel Beltrá: I contacted Greenpeace and arranged to board a ship going to the Balearic Islands. I told

my EFE picture agency editor I wanted to go with

Greenpeace on assignment for two weeks. The editor

laughed in my face, saying, "There's no way I am going to pay you to take a two-week holiday on a boat."

Jokingly I replied, "If I take vacation time and produce

a good story would you distribute it?" He agreed and

disseminated my resulting story.

This lead to Greenpeace asking me to do more pieces,

though I couldn't as an EFE staff photographer. In the

early 1990s, I relocated to Paris and became correspondent for the French picture agency Gamma, allowing

me to freelance with Greenpeace and photograph the

subjects I deeply cared for. Conservation photography

was a profession I didn't even know existed. It felt like

we were inventing a new field. I moved to the States in

2002, and that's the only thing I have been doing since.

RH: How did Gulf oil spill series come about?

DB: I got a call from the Greenpeace USA photo

editor. He said, "Daniel" and I replied, "Oil." I knew.

They only had funds to cover four days of aerial surveys to see what was up as there was no oil near the

coast. Fortunately, I ran into a lady from Alabama

who was quite concerned about what was happening,

saw my printed work, and funded additional flights

over a two month period.

RH: What does your aerial work reveal that is not

evident from eye-level?

|

Volunteers of the Tri-State Bird Rescue and Research and the International Bird Rescue Research

Center run a facility in Fort Jackson, Louisiana, where they clean birds covered in oil from the Deepwater

Horizon wellhead. By November 2010, around 8,000 birds had been collected; 6,100 of those were dead. phototechmag.com 35

|

DB: Making photographs in the air reveals a sense of

scale. Also, what separates my work from many photo-

journalists is that my photographs turned out to be

quite beautiful. This has allowed me to put work in

public places, such as galleries and aquariums, where

they have a longer life and larger audiences.

RH: How do you reconcile making beautiful pictures

of horrible events?

DB: I can sleep relaxed at night knowing I was not trying to make beautiful photographs, rather I am following my spirit. When I see the positive reaction to the

work I feel good about it as it keeps the subject and

discussion out there. Because everything goes so fast,

many environmental photographs with a hard-core

photojournalism approach are quickly forgotten.

I want to make effective photographs that have an extended life. I never intended the work to be thought of

as Art, but that is how it has started to be considered.

RH: Do you think of your work as art, reportage, or

post-documentary, in which a maker actively incorporates his voice?

DB: In my heart I am a photojournalist who is telling

a story about a subject I am concerned about. If I

manage to build a bridge between hardcore photojournalism and the art world when these photos hang on a museum wall, then I am happy.

I had a fine arts show in Aspen, Colorado in which three, large, abstract pieces were in the front of the gallery and people walked in and thought it was a painting exhibition. That was not my intent, but it is a great opportunity for a completely different crowd to see my work. It resulted in an exhibition at the Seattle Aquarium. I don't think they would have done a show of hardcore photojournalism.

The exhibition opened on the first anniversary of the oil spill and ran five months during peak tourism season. Half a million people had the chance to see it, that's incredibly important for me. Now the show is going to the Long Beach California Aquarium where another half a million people can see the work. There are not many photographs of the Gulf oil spill that we still see a year later. For me the key issue is how to be initially effective when an event happens and then for the photographs to have an afterlife.

RH: What role does Photoshop play in your work?

DB: I shoot RAW files and make adjustments to the contrast and saturation, but nothing is added or subtracted from the original capture.

RH: How do you print your large images?

DB: The largest print, The Pelicans, is 48 x 60-inches and it is stunning. When I was in the Gulf I met the photographer Edward Burtynsky whose work explores how nature is transformed by industry. There was a little drama, as my printer couldn't make the deadline for the Seattle show. Ed stepped in and offered to make them in his Toronto studio and so I printed the images there. It was a phenomenal experience, it was like a painter getting to go to Picasso's studio.

Oil released from the failed Deepwater Horizon wellhead rises up to the surface of the

Gulf of Mexico amidst

an offshore platform drilling a relief well.

RH: What would you suggest to someone starting a photographic project to consider?

DB: Follow your passion and act locally so you have ongoing access to your subject. Then ruthlessly edit, edit, edit.

RH: Your approach brings to mind Cornell Capa's

concept of the Concerned Photographer in which "The role of the photographer is to witness and to be involved with his subject."

DB: I remain optimistic. If I were dumped in the middle of a lake, I would swim to shore the best I could. Regardless of one’s political views, we all live on this planet and share the responsibility to care for it.

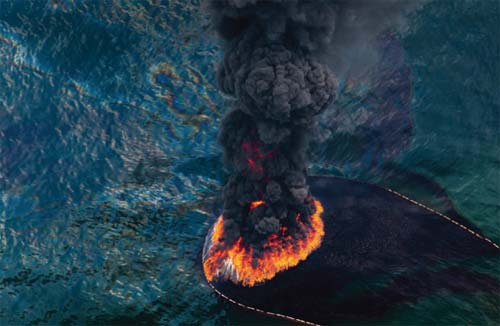

A plume of smoke rises from a burn of collected oil. A total of 411 controlled burns were used to try rid the

Gulf of the most visible surface

oil from the BP Deepwater Horizon wellhead.

Resources

Daniel Beltra - danielbeltra.com

Greenpeace - greenpeace.org/usa/en

Edward Burtynsky - edwardburtynsky.com

Robert Hirsch is author of Exploring

Color Photography: From Film to Pixels;

Light and Lens: Photography in the

Digital Age; Photographic Possibilities:

The Expressive Use of Equipment,

Ideas, Materials, and Processes; and

Seizing the Light: A Social History of

Photography. Hirsch has published

scores of articles about visual culture

and interviewed eminent photographers

of our time. He has had many one-person shows and curated numerous

exhibitions. The former executive

director of CEPA Gallery, he now heads Light Research. For details

about his visual and written projects visit: lightresearch.net. Article

©Robert Hirsch 2012.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|