Regarding the Pain of Others

By Robert Hirsch

Photovision, May/June 2003, 10 - 12

Today nobody gives much thought to the quality and quantity of writing about photography. But this was not always the case. Whether you agree with her observations of not, the publication of Susan Sontag's On Photography in 1977 was a innovative event that marked the first time an American Intellectual seriously considered photography worth thinking and writing about. Ironically the dramatic increase in scope and excellence of photographic writing, for which Sontag deserves credit for stimulating, has reduced the effect of what she has to say in Regarding the Pain of Others, (Susan Sontag, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $23.00, ISBN 0-374-24858-3) because much of the material has already been stated. However, this short collection of nine essays that investigates how pictures, from Goya's The Disasters of War to New York City on September 11, 2001, represent atrocity, trauma, and violence provoke more topics that can be discussed in this review.

Sontag begins with the statement that men make war, but immediately shifts to how the collective "we" looks at other people's pain. She concludes that grisly photographs confirm people's previously held opinions. For instance, in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, what matters is who kills whom, and that identity determines one's response to killings. Sontag deduces "that painful photographs supply no evidence, none at all, for renouncing war-except to those for whom the notions of valor and of sacrifice have been emptied of meaning and credibility." The result is that photographs of atrocities can produce opposing responses ranging from a call to peace, a cry for revenge, or the absentminded perception that photography reports on endless terrible happenings.

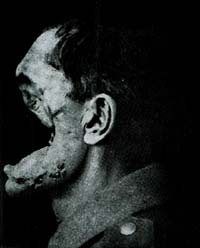

As I write this, the US stands at the brink of war with Iraq, Sontag vividly construes that if photographs had the power to stop killing then battles would have ended with the publication of German anarchist and pacifist Ernst Friedrich's War Against War (1925), which is still shocking. Sontag points out that even Friedrich did not rely on the raw power of 180 photographs he culled from the German military and medical archives of World War I, but steered their meaning through juxtaposition and the use of impassioned and acerbic caption mocking military ideology and the sickening horror of war.

Here in lies my biggest disappointment; there is nothing to look at in this book. Sontag constantly refers to images, and their absence is distracting because readers have to attempt mentally to recollect each picture, limiting the response to those already familiar with the works. The missing visceral punch of such images limits the realm of knowing to the word, whereas a richly illustrated book could have enhanced Sontag's arguments through the interaction of reading, seeing, and reflecting.

Early on Sontag discusses the phenomena of how people who have not experienced war try to comprehend it from photographs. She provides a mini history of war try to comprehend it from photographs. She provides a mini history of war photographs are quotations traced from something before the camera's lens that we stock in our brain and is subject to instant recall. Sontag states that the immediacy and authority of images, such as Robert Capa's Spanish Civil War photograph The Falling Soldier, 1939, are superior to other ways of conveying the horror of death. This, she observes, is because people prefer atrocities to be presented with the weight of witnessing, but without the taint of artistry, for people often object to photographs that aesthesize suffering. Sontag knows that photographs can transform a subject, in the manner that Joel Meyerowitz makes the ruins of the World Trade Center beautiful. The skilled use of aesthetics can draw attention to the medium of photography itself. This becomes undesirable to those who want to maintain the photograph's traditional role as an automatic document; a limitation not tolerated in other mediums.

Sontag discusses Here is New York: A Democracy of Photographs (project previously reviewed), now available as a book (Scalo, $50, ISBN 3-908247-66-7) that ehibited images related to the attack on the World Trade Center that were made by anyone with a camera. She zooms in on the show's subtitle and extends the notion that photography is the only art in which professional training and experience does not confer an advantage over the untrained and inexperienced. Sontag observes how chance can favor the spontaneous and the imperfect. This she says falls in step with the anti-art prejudices of the cultural elite and how these values are the opposite of those of literature where the refinement of language is highly valued.

Sontag intentions are not inherent in a photograph and that meaning is situational and in flux. She reminds us that Larry Burrow's Vietnam color photographs that appeared in Life were once emblematic of war gone "bad", but since the rise of patriotism following 911 have become symbols of heroic obligation ( see Larry Burrows Vietnam with an introduction by David Halberstam, Alfred A. Knopf, $50, ISBN 0-375-41102-X).

In retrospect, the Vietnam War coverage brought home the point that dead civilians, especially women and children, upset people. Photographs like those made by Burrows continue to hammer at the myth that war is fought only by "real men" on remote battlefields and makes us realize that the majority of the casualties are noncombants. The mass circulation of such war images does not permit us to distance ourselves from or romanticize death and destruction, nor however do they tell us how best to confront evil.

With the lesson of Vietnam in mind, what sort of access will the U.S. government allow journalists in the event of war with Iraq? Sontag contends censorship is contingent on circumstances. For instance, the video confession and murder of American journalist Daniel Pearl in Karachi was suppressed as a snuff piece allegedly to spare his widow additional pain and also not to give voice to the terrorists political statements and demands. On the other had, Sontag says that images from more remote and exotic places are more likely to have full frontal views of the dead and dying (not American) without worry as to how their families might respond to the images. The constant flow of horrific photographs, such as villagers in Africa dying of AIDS, takes on the atmosphere of an "ethnological exhibition" that reinforces the belief that tragedy is to be expected in such "backward"places.

Sontag does not think that images we continually see inevitably lose their power to shock. She perceives that certain images, such as representations of the crucifixion, never become banal to believers and serve as an emotional release for grief that allows us to cry over pathos and feel better for having acknowledged it. Although Sontag has faith in the power of photographs to haunt, like the Nazi concentration camp photographs that she saw as a child, she states that photographs do not provide us much assistance in comprehending a situation. Sontag sees this struggle for meaning as the domain of writers like her to create narratives that help us understand what is taking place. Sontag firmly believes that photographs of death camps or lynching can awaken us to a situation and may produce strong emotional reactions, and give ruse to numerous questions and calls to action, but their meaning is free-bloating and can only be anchored down by words. She also cautions against solely relying on photographs for remembrance because they blot out other forms of remembering and understanding, leading us to recall only the photograph of the event and not the story that goes with it.

Sontag points out that pictures of anguish, such as Goya's series of 82 etchings The Disasters of War, arose prurient interest through their ability to simultaneously repel and attract. In 1757 Edmund Burke wrote that people take a certain pleasure in the misfortunes of others. My grandmother would laugh if she saw someone stumble, revealing the complex entanglement of mischief and cruelty with good deeds and sympathy that make up the human psyche. Images of suffering can allow us to face taboos, which Sontag believes is necessary because passivity dulls feelings and produces impotence.

© Jeff Wall, Dead Troops Talk (A Vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol near Mogor, Afghanistan, Winter 1986), 1991 - 92. Dye destruction transparency, 90 x 164 inches. |

Another aspect of this phenomena can be seen in the Mutter Museum of College of Physicians of Philadelphia (Gretchen Worden, Blast Books, $50, ISBN 0-922233-24-1), which presents a blend of historic and by contemporary photographs by artists such as Gwen Akin and Allan Ludwig, Rosamond Purcell, and even William Wegman that utilize a collection of medical abnormalities whose disconcerting beauty provides a glimpse into the margins of the human form. Once past the sense of repulsion, the question what physically constitutes a human becomes paramount.

Sontag also revises topics in On Photography, such as whether repeated viewing of photographs shrivels sympathy. She stirs the academic caldron by proclaiming that reality is not dead and calls Guy Debord's "society of spectacle" and Jean Daudrillard's "simulacra" fancy rhetoric of "breath-taking provincialism." She criticizes these postmodern theorists as a privileged few that ignore the condition of the majority who "do not have the luxury of patronizing reality" and do not want their pain to be commingled with that of others.

Sontag closes by shifting back to a question she says is more likely to be raised by women, "Is there an antidote to the perennial seductiveness of War?" After building her points with documentary type images, she concludes with Jeff Wall's canvas size fabricated photograph Dead Troops Talk, (A Vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol near Mogor, Afghanistan, Winter 1986) 1992, as a mediation on war. This 7 1/2 x 13 feet light box tableaux, inspired by Goya, imagines thirteen dead Russian soldiers who appear "supremely uninterested in the living." This is significant, for it acknowledges the role of the artist in representing physical and psychic pain. It dismantles the lingering and limited notion that a photograph is an objective mirror, instead of an expressive medium capable of portraying multiple realities. From this image Sontag circles back to the collective "we" and concludes that we who have not directly experienced "their" specific dread and terror, cannot understand or imagine their suffering.

So why do people continue to make and seek such images? Sontag's writings about distressing images remind us that we are suspended in a tragic stage, but also encourage the contemplation of that gray area between the affirmation and negation of life. Sontag states that remembering is an ethical act, yet the only way to make peace is to let go (forget). She speculates that it is not the quantity of catastrophic images that is problematic, but that our capacity to think about the suffering of others has not progressed so we turn away from images of pin because they make us feel powerless. What might make a difference? Possibly taking the time to stand back and think, for a greater awareness of the inescapableness of tragedy might bestir a brave few to disarm distress through tiny individual acts. As Sontag states: "Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers." Perhaps someday these seemingly small acts (including photography) will eventually help us step away from the endless, stupid parade of mayhem, murder, pornography, sadism, spectacle, and violence.

|

|

Regarding the Pain of Others by Susan Sontag. Francisco de Goya. Tampoco, Plate 36 from the series The Disasters of War, 1810-20.

War Against War by Ernst Freidrich. The "health resort" of the proletarian. Almost the whole face blown away, page 217. |

|

Larry Burrows Vietnam (jacket cover): Larry Burrows, Second Battalion, 5th Marines, operating near the DMZ, October 1966.

|

Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia by Gretchen Worden (jacket cover): Arne Svenson, Untitled, No. 19, 1990.

|

|

|

|

|