|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flexible Images: Handmade American Photography,

1969 – 2002

© Robert Hirsch 2003

Published in The Society for Photographic Education’s exposure, Volume 36:1, 2003, cover and pages 23 – 42.

|

|

|

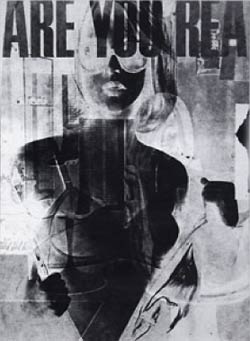

Figure 1. © Robert Heinecken. Are You Rea #1, 1966. Gelatin silver print. 11 x 8-1/2 inches. Courtesy Pace MacGill Gallery, NY.

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. © Naomi Savage. Enmeshed Man, 1966. 17 x 14 inches. Photoengraving on copper with silver plating and black acrylic paint.

|

|

|

|

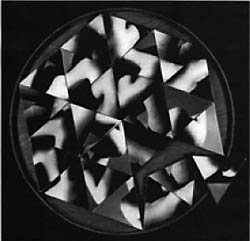

Figure 3. © Robert Heinecken. Reflactive Hexagon, 1965. 16-inch diameter. Gelatin silver prints on wood. Courtesy Pace MacGill Gallery, NY.

|

|

|

|

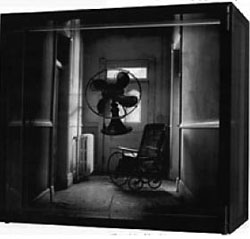

Figure 4. © Douglas Prince. Untitled, 1969. 5 x 5 x 2.5 inches. Film and Plexiglas.

|

|

|

|

Figure 5. © Jerry Uelsmann. Small Woods Where I Met Myself, 1967. 10-3/8 x 12-3/4 inches. Gelatin silver print.

|

|

|

|

Figure 6. © Robert Fichter. World War I Soldiers, 1970. Cyanotype with watercolor. 14 x 18 inches. Courtesy of Jerry Uelsmann Collection.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7. © John Wood. Pop Goes the Weasel, circa late 1960s. 7-3/4 x 9 -3/4 inches. Photographic collage.

|

|

|

|

Figure 8. © Bea Nettles. Florida Moonrise, 1977 (from Flamingo in the Dark, 1979). 20 x 26 inches. Bichromate on vinyl (Kwik print).

|

|

|

|

Figure 9. © William Larson. Transmission 0035, 1974. 8-1/2 x 11 inches. Electron-carbon print.

|

|

|

|

Figure 10. © Robert Hirsch. Illuminated Man, 1972. 11 x 14 inches. Toned gelatin silver (Kodalith) print.

|

|

|

|

Figure 11. © Thomas Barrow. Teepees, 1979. 18 x 19 inches (irregular) Reconstructed gelatin silver print with caulking, staples, and spray paint. Courtesy of the Center for Creative Photography.

|

|

|

|

Figure 12. © Lucas Samaras. Untitled, 1974. 4 -1/4 x 3 -1/2 inches. Diffusion transfer print. Courtesy the Polaroid Collections.

|

|

|

|

Figure 13. © Judith Golden. Rhinestones, 1976. 14 x11 inches. Gelatin silver print with oil paint and glitter.

|

|

|

|

Figure 14. © Robert Flynt. Untitled, 1990. 10 x 8 inches. Chromogenic color print.

|

|

|

|

Figure 15. © Pat Ward Williams. Accused/Blowtorch/Padlock, 1987. Size varies, approximately 72 x 96 inches. Caulk text, film positive, gelatin silver prints, magazine page, paint, and window frame. [Production note: Reproduce image so the text is readable or print full text below the image].

|

|

|

|

Figure 16. © Dinh Q Lê. Untitled (from Cambodia: Spendour and Darkness), #11, 1999. 40-1/4 x 58-1/4 inches. Chromogenic color prints and linen tape. Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica, CA.

|

|

|

|

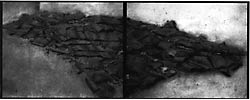

Figure 17. © Tatana Kellner. House Fire – Forgotten Survivor, 1990. 72 x 50 inches. Altered gelatin silver print.

|

|

|

|

Figure 18. © David Levinthal and Garry Trudeau. Hitler Moves East, 1977. 8 x 10 inches. Gelatin silver (Kodalith) print. Courtesy Paul Morris Gallery, New York City.

|

|

|

|

Figure 19. © Mike and Doug Starn. Double Rembrandt with Steps, 1987 – 88. 108 X 108 inches. Toned gelatin silver print, toned ortho film, wood, Plexiglas, and glue. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY.

|

|

|

|

Figure 20. © Holly Roberts. Woman with Black Cloud, 1989. 25 x 30 inches. Oil on gelatin silver print.

|

|

|

|

Figure 21. © Robert ParkeHarrison. Mending the Earth, 1999. 40 x 47 inches. Gelatin silver print with mixed media.

|

|

|

|

Figure 22. © Vik Muniz. Picture of Dust (Barry Le Va, Continuous and Related Activities; Discontinued by the Act of Dropping, 1967, Installed at the Whitney Museum in New Sculpture 1965-75: Between Geometry and Gesture, February 20-June 3,1990), 2000 (from the series The Things Themselves: Picture of Dust). Framed, overall: 51 x 130 1/2 inches. Two silver dye bleach prints (Ilfochrome). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York;/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

|

Shortly after they were brought forth as unadorned infants in the mid-nineteenth century, daguerreotypes and calotypes were marked on and colored by photographers who decided to overcome the monochromatic limitations of these images and to achieve more realistic appearances.1 One would have thought that such practices would have rendered the malleability of photography apparent from its beginnings, but this was not the case. It appears that people were so bedazzled by permanent light drawing that until the recent widespread use of digital imagery, they largely ignored how the human hand has so frequently revised the so-called mechanical objectivity of photographs both before and after the moment of exposure.2 This article surveys significant work and ideas that have constituted the phenomenon of handmade photography from its resurrection in the 1960s to the present. The artists presented share a desire for subjective expression, a confidence in the untamed imagination, an aversion to dogma and fixity, and a refusal to accept a deterministic view of the role of the individual in society, no matter how reasonably the idea of determinism may be put forth. This article outlines some of the varied methods these artists have used to question conventional photography, to convey internal realities, and to critique history and the concepts of truth and self.

There is some question as to what to call the manner of working that these artists employ. It has commonly been referred to as alternative, hand-altered, or manipulated photography. These terms were coined during the 1960s in the spirit of counter-cultural rebellion against an entrenched body of photographic technique. Unfortunately, today these terms are tainted by a lingering prejudice against counter-culture values. In addition, the ideas of alternative or manipulated processes carry a subtle negative connotation in that they are taken to imply that the work they describe falls short of or corrupts an acceptable standard. To avoid such negative undertones and to convey how our hands have the power to direct creation, this article refers to the photography in question as handmade photography.

The resurgence of handmade photography in the 1960s had several sources and influences. It looked back to the “anti-tradition” of nineteenth-century romanticism, which accentuated the importance of making a highly personal response to experience and a critical response to society. It drew on contemporary popular culture. Many of the artists engaged in this movement were baby-boomers brought up on television and film, media that often portrayed photography as hip and sexy—e.g. the film Blow-Up (1966)—and which drove home the significance of constructed photographic images. In addition, the widespread atmosphere of rebellion against social norms propelled the move toward handwork. The rejection of artistic standards in photography was consistent with the much broader exploration of sexual mores and gender roles that took place in the sixties. It was also consistent with the exploration of consciousness. The latter was encouraged by such counter-culture figures as Ken Kesey who, with his band of Merry Pranksters, boarded a Day-Glo bus called "Further" and took an LSD-fueled trip across the country that echoed Dr. Timothy Leary’s decree “to tune in, turn on, and drop out.”3 On a broader level, the society-at-large was exposed to psychedelic exploration through Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which youthful audiences saw as a mysterious consciousness-expanding trip into humanity’s future. Finally, handmade photography was supported by the general growth of photographic education in the university. The ubiquity and importance of the medium in the culture at large, as well as pressure from those who championed photography from within art institutions gave credence in the post-war decades to the idea that people could study photography seriously. As new photography programs mushroomed in the universities, they produced graduates who took teaching positions in even newer programs. Many of these young teachers, who had grown up to the adage of “do your own thing,” were responsive to unconventional ways of seeing and working, and they encouraged these attitudes in their students, many of whom turned to handmade photography.

Despite the attractions of handmade photography there were in the sixties, and still are to some degree, emphatic objections to the open engagement of the hand in photographic art. One common objection is that such art constitutes a dishonest method to cover up aesthetic and technical inadequacies. Another comes from those who believe strongly in the Western tradition of positivism. These people tend to reject handmade photography on the grounds that it is unnecessarily ambiguous or irrational in its meanings. Nevertheless, more artists than ever are currently using the flexible, experiential methods of handwork. In addition to opening up an avenue to inner experience, artists find handwork attractive because it promotes inventiveness, allows for the free play of intuition beyond the control of the intellect, extends the time of interaction with an image (on the part of both the maker and the viewer), and allows for the inclusion of a wide range of materials and processes within the boundaries of photography.

Robert Heinecken, a printmaker at UCLA, was an important figure in promoting new ways of being a photographer. In a 1969 “debate” with Ansel Adams at Occidental College in Los Angeles, Heinecken made it clear that he and other up-and-coming artists with maverick and rebellious natures had every intention of upending the dominant modernist, objective concepts of photography in their broad desire to challenge conventional systems of thought.4 Heinecken is a gadfly who uses the elements of play and wonder to question everyday assumptions and seek out associations among presumably divergent subjects. His work combines various mediums to fashion witty, sardonic, and unexpected cultural connections among food, the media, sex, and violence. He uses “found” photographs rather than going out and making them. His subject matter, his appropriation of existing images, and the constructed appearance of his finished work—which can be three-dimensional—all make his approach the antithesis of the straight photography that was dominant in the 1960s and that Ansel Adams, with his transcendental landscapes, quintessentially represented.

In his Are You Rea series, Heinecken contact printed magazine pages with sexually suggestive photographs of women so that both sides of each page could be seen simultaneously in one blended image. This technique reveals unexpected visual and textual interactions. The fragmentation of the text is particularly provocative and is indicative of an anti-illustrative impulse toward evocative meaning. Could rea stand for real, ready, or reasonable? The intuitiveness and openness of Heinecken’s technique exemplifies a nondoctrinaire approach to the sexually charged material and suggests that social truth is relative.

Peter C. Bunnell was a groundbreaking promoter of handmade photography in his role as a curator. The year before the Heinecken/Adams debate, Bunnell mounted Photography as Printmaking at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York City, an exhibit that featured 72 works by 23 artists. One of the artists was Naomi Savage whom Bunnell credited with having “extended the photographic medium by her presentation of the photoetched plate itself. A simple act, but in its generosity she has brought to the medium a kind of topographic photograph, which modulates forms in three dimension with a variety of metallic surfaces and tones.”5 This three-dimensionality and fine texture was so unusual that viewers could not always accept Savage’s work as photography. But Savage’s photography is more than a technical tour de force. In Enmeshed Man (1966) she uses her technique to explore the complex relationship between internal and external experience and the indefinite boundaries between the two.

The prominence of Savage in Photography as Printmaking demonstrated a parallel between the technical liberation that this new generation of artists practiced and social emancipation that provided entrée for women into world of art.

In 1970 Bunnell followed Photography as Printmaking with Photography Into Sculpture, an exhibition at MOMA that featured works by 52 artists. This exhibit showed how artists were carrying the three-dimensionality of work like Savage’s to even greater lengths and embracing “a new kind of photography in which many of the imaginary qualities of the picture, particularly spatial complexity, have been transformed into actual space and dimension.”6 This embrace of three-dimensionality in photography broke emphatically from the modernist dictum that no artistic medium should take on attributes of any other medium.

In Photography Into Sculpture, Heinecken teased the audience with picture puzzles, such as Reflactive Hexagon, (1965), in which 24 close-up photographs of a woman’s body are adhered to wooden blocks. No matter how hard viewers tried to fit the pieces together, it was not possible to make the subject whole, reminding them that all representational images are illusions. Heinecken was “not interested in the simple character of the camera for art.” His methodology drew on his earlier studies in literature that gave him the means to “reconstruct image and content to resemble free verse poetry.”7

Douglas Prince was represented in Photography Into Sculpture by six sealed Plexiglas boxes (all in a single rear-illuminated case), each containing an image that consisted of several sheets of black-and-white positive film, spaced at slight intervals.8 The intimate scale of these artworks, and particularly the superimposition of translucent images, engaged exhibition visitors, encouraging them to spend more time contemplating them than they would a conventional photograph. The multi-layer film construction produced an experience of blending scenes that constantly recombined as the viewer moved through space. Even though one knew that the individual images were fixed, their meanings changed with every shift of one’s eye. Prince replaced the presentation of a single static reality that one sees in a conventional photograph with a work that suggests the possibility that many different worlds coexist.

Bunnell’s innovative exhibitions demonstrated that in essence photography is nothing more than light sensitive material on a surface. The exhibitions also recognized that the way a photograph is perceived and interpreted is established by artistic and societal preconceptions about how a photographic subject is supposed to look and what is accepted as truthful. The work in the Bunnell exhibitions was indicative of a larger zeitgeist of the late 1960s that involved leaving the safety net of custom, exploring how to be more aware of and physically connected to the world, and critically examining expectations with regard to lifestyles.9 For the artists in these shows the camera-defined image was only a beginning that inspired a “postvisualized” image, brought about by their direct physical involvement in its creation.

Jerry Uelsmann, another principal figure of the handmade photography movement, had articulated the concept of postvisualization. Uelsmann, who taught at the University of Florida, Gainesville, outlined the idea in a paper he delivered in 1966 at a Society for Photographic Education conference in Chicago, urging photographers to consider the darkroom to be “a visual research lab; a place for discovery, observation and mediation. … Let us not be afraid to allow for ‘post-visualization.’ By post-visualization I refer to the willingness on the part of the photographer to revisualize the final image at any point in the entire photographic process.”10 Uelsmann’s remarks focused on the darkroom as the place of photographic creation. He and many other photographers respond intensely to the darkroom experience. The dimly glowing light, the sound of trickling water, and the acrid smells of acetic acid and fixer rising from the sink create an otherworldly environment that alters customary space and time, spurring the senses to circumvent the confines of familiarity and predictability. Uelsmann’s darkroom creations revived the art of combination printing. With consummate skill, he exposed his light sensitive paper through a series of enlargers, each holding a different negative. The results disturbed the conventions of the photographic timespace continuum. Uelsmann enhanced the provocativeness of his imagery with poetic titles, such as Small Woods Where I Met Myself (1967).

This kind of image did not provide the concise message that people had grown to expect from photography through their experiences with mass media, such as Life magazine, in which editorial committees embedded photographs in highly tendentious text that was designed to insure that the viewers were getting the “right” message. Uelsmann’s sense of fantasy defied these expectations by opening a private window into a reality that grasps the inwardness of a subject that lies beyond its external form. This approach can be linked to the Japanese concept of “shashin,” which states that something is only true when it integrates both the external appearance with the inner makeup of a subject. Uelsmann’s art fosters an open, dynamic relationship between artist, subject, and viewer. Small Woods Where I Met Myself can be interpreted as a reflection of American society’s growing sense of doubt about everything from abortion, to the Vietnam War, to the possibility of assigning meaning to art or life. The work signals the growing awareness that meaning is unfixed, that it changes according to the interplay between the maker’s intentions and the viewer’s understanding. Where there had once been a sense of assurance, ambiguity now prevailed.

Robert Fichter—who studied with Jerry Uelsmann and Henry Holmes Smith, before taking a teaching position at Florida State University in 1972—has worked with collage, cyanotype, gum bichromate, hand coloring, and Verifax.11 Fichter considers himself “an experimentalist, a narrative artist whose interest is in the expression of some of the questions raised by human existence.”12 The series of images that he used to create World War I Soldiers (1970) were made on May 4, 1969, the day the National Guard shot and killed four people at Kent State University during an anti-Vietnam War demonstration. Such shocking events can fracture the ordinary flow of experience, and the sudden and intense passions they arouse can create a condition that encourages an artist to break lose from previously felt imaginative constraints. Fichter’s open embrace of unconventional photographic materials—cyanotype with watercolor washes—parallels a desire to reject the confines of the dominant political and social worldview of the time. His photographic process became a kind of social protest. As Fichter put it, “I wanted to break free of commercial restrictions and think outside of the Yellow [Kodak] box.”13

The new culture of visual options found fertile ground in the Western New York region where the George Eastman House, the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), and a strong photography program at the University of Buffalo supported vigorous innovation among two generations of photographers.14

While working at the George Eastman House, publishing Aperture, and teaching at RIT from 1953 to 1965, Minor White had nurtured the belief that there was no chain of command in the arts and that “alternative” paths could be pursued at any point of the creative process.15 The spirit of White’s teaching was evident in the work of John Wood, a photographer and printmaker who taught at Alfred University in southern New York from 1955 to 1989. Consistent with his “political and aesthetic beliefs that there is no hierarchy between processes, materials, and ideas,” Wood felt “the need to use all the visual media available to me.”16 He combined pictures from magazines, newspapers, television, and his own resources to make images, such as Nixon and Agnew (Pop Goes the Weasel), circa 1969, which presents a social commentary that stretches the boundaries of previsualized imagery.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s Rochester was a hothouse for artists who thought that photographic description alone would not necessarily unveil the potency of a subject.17 Betty Hahn, Judith Harold-Steinhauser, and Bea Nettles all taught at RIT during this period, and all stressed methods that made use of allusion, indirect reference, and suggestion, approaches that gave their work an enigmatic quality. Their work could slip around the empirical defenses of reason and deliver powerful, personal messages to an audience willing to search for meaning.

In her self-published book, Breaking the Rules: A Photo Media Cookbook (1977), Nettles promoted many of the methods these women worked with—such as cyanotype, gum printing, and Kwik Print—to a larger audience.18 Nettles adopted the Kwik Print on vinyl, a graphic arts proofing method in her artists’ book, Flamingo in the Dark (1979), to her own soft painterly way of working. Her earlier art often resonated with the sensibilities of other female photographers in that she used techniques traditionally associated with women that combined sewing machine stitching and cotton stuffing with autobiographical images. One purpose of using such traditionally “female” techniques was to acknowledge that such processes had a history of practice among women and to elevate that history and the processes themselves to a higher artistic status than they had enjoyed in the past.

In his series, Fireflies 1970 – 1976, William Larson, who had studied at the University of Buffalo in the 1960s, looked beyond the gelatin silver aesthetic by using a proto-fax machine, which converted pictures, sound, and text into audio signals. The machine transmitted these signals over a telephone line onto special receiving paper, forming a highcontrast image (a facsimile). Larson controlled the printing process by hand. He also sent multiple transmissions onto the same paper, building up images over time whose ambiguous messages used new information technologies to allude, as his title suggests, to the ephemeral flight of a firefly. Larson’s working methods not only transverse customary media boundaries but also challenge our preoccupation with the literal identification of photographed subjects. Larson’s expressive image is a personal reference to the natural world made through the latest technology under the control of the artist’s hand and imagination.

While completing his BFA at RIT (1971), Robert Hirsch began defying the modernist fine print aesthetic and its classical range of tonal values by printing his images on Kodak Kodalith paper.19 This challenge was further developed in his Underground City series (1972 – 1976) where he disturbed the way that photographic information is normally recorded in the enlarging process by filing out the edges of his negative carrier and moving the fine-focus enlarger control as he exposed a print. In his camera work, Hirsch constructed compositions that he then illuminated at night by direct flash, intentionally washing out detail. Later, using electronic flash, penlights, and fiber optics, he also introduced hand-controlled bursts of light during the camera exposure and/or the making of the print. These processes of impulsive marking expressionistically charge specific areas of a scene; create visual motion and volatility in a print; eliminate unwanted elements in a composition; and convey the artist’s emotional sensations about a subject, all by utilizing photography’s fundamental ingredient—light.20

Thomas Barrow, who was on the Eastman House curatorial staff from 1965 – 1972, worked with numerous experimental processes that pried the photograph away from the mentality of the witness stand. In his Cancellation series (1974-1978), Barrow slashed an “X” onto the negative to point out that regardless of how much empirical data is knowable, reality remains a makeshift combination of belief, ignorance, and knowledge. Barrow also agitated the photographic surface by adding caulk, spray paint, and staples, which provided a challenging model dealing with the complexity and the difficultly of deciphering any image.

The handwork movement, which generated such intense and varied activity in the western New York region, spread to other parts of the country in the 1970s. In much of this work artists focused on issues of identity: its construction, distortion, celebration, or suppression by the forces of the larger society and by the actions of the individual. The artists who engaged with these issues often used their art to question or undermine common categorizations and stereotypes and to assert their sense of self.

In his Photo-Transformations (1975), Lucas Samaras used the Polaroid SX-70 to incorporate his explosive, gestural impulses (which he had used in his paintings) directly into the photographic medium.21 By manipulating the surface of the Polaroid print before its dye layers had hardened, he produced images in which his body spreads, stretches, and erupts. It is as if we were witnessing the supernatural effects of a psychedelic drug experience. Samaras’s use of his hand to reconstruct his own image brings to mind the existentialist idea that we constantly define human nature through our choices and actions. But Samaras’s distortions are so radical and so varied from one photograph to the next, which he calls into question the very stability of the self, suggesting that we construct, deconstruct, and reconstruct ourselves many times, often violently.

During the mid-1970s Judith Golden employed her haptic22 sensibility in her Magazine Makeovers to explore the effects of advertising on popular beliefs and fantasies about women. In Rhinestones (1976), Golden created a composite mask in which her own face peeks through a partially torn and crinkled fashion magazine photograph of an unknown model. Golden thus points to the way women are defined by youth culture and the fear of aging. Her layered technique (her use of hand-coloring and bits of text, as well as several images) creates a sense of temporality in her work that suggests personal history: the construction of a present self through past actions.

Robert Flynt addresses issues of gay activism in the time of the AIDS pandemic. In the 1980s, Flynt began making black-and-white negatives of male figures that he incorporated in the darkroom with what he calls “photogrammic elements,” such as anatomical drawings on acetate, to form images that he printed on chromogenic color paper. The merging of these transparent overlays into the photographic image, along with painting the print with color chemistry and the use of solarization, form contradictory lexicons of representation. There is a sense of play here—a participatory and directorial process that Flynt engages in with his materials—that resolves the outcome of his work. Flynt says “I am interested in the confrontation of the figure and the universe, from the micro to the macrocosm, interior to exterior; there has been no meaningful way for me to explore this without incorporating manipulation. I wanted to convey the tension between the diagrammed and the photographed [figures] and add to the ambiguity in the erotic/morbid tone of the photographed nude male figures during a time when the equation of (gay) sex equals death was becoming pervasive.”23

In works, such as Accused/Blowtorch/Padlock (1987) 24, Pat Ward Williams takes on bigotry and intolerance by using a photograph originally made to intimidate African Americans—one showing the murderous end that could befall black men who did not observe Jim Crow rules. Williams converts this image into a call against racism. She does so by shifting the status of the photograph from that of a report to that of a subjective statement embedded in the issue under investigation. Williams’s combination of scrawling blackboardstyle text and the anonymous Life magazine photograph conveys not only the sickening image of a black man chained to a tree and tortured to death with a blowtorch, but also a series of questions and comments about the photograph and the scene it depicts. The result invites the viewer to identify with different selves: that of the murdered man, those of the witnesses to this crime, and perhaps even those of the perpetrators.

Dinh Q Lê deals with persecution through a modified method of grass mat weaving that he learned from his aunt in Vietnam before the Khmer Rouge invaded his village and forced his family to flee to the United States. Lê cuts his color photographs into long strips and then weaves them together. He thus fabricates a new interconnected reality that is often based on opposite viewpoints. In his series, Cambodia: Splendor and Darkness, Lê handles atrocity with meditative calm, combining images of stone carvings from the temples of Angkor Wat with stark frontal portraits of the people murdered by the Khmer Rouge. His ghostly images invoke a profound sense of alienation and hopeless isolation, which raise metaphysical questions about the nature of evil.

Lê was directly touched by the history that fuels his art. Other artists similarly draw on the historical events that have shaped their sense of self. Tatana Kellner, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, relies on her memory and her training as a printmaker to create multimedia assemblages that reveal how the Holocaust and the experiences of her family have shaped her identity.25 She is fascinated by the ceaseless human quest for dominance over others, and from this perspective, she views history as a constant process of struggle and loss. Kellner says: “Covered in dust, rubble, and layers upon layers of sediments, history is only revealed after digging up a lot of dirt, both physically and figuratively. I work with images in a similar way, digging through layers to try to uncover the meaning. Complex events possess different interpretations; depending on whose vantage point we’re looking from. I’m conscious of this and try to present an ‘historical truth’ before the viewers, leaving space for their own analysis and understanding.”26 Kellner’s work reminds us that history is a reflection of our own perceptions and preoccupations, thereby making all history contemporary.

If Kellner attempts to present a historical truth, while remaining aware that such truth may be slippery, David Levinthal and Garry Trudeau have challenged commonplace historic realities and the assumption that we can know history with any degree of certainty. In their collaborative effort, Hitler Moves East: A Graphic Chronicle, 1941 - 43, 1977, they juxtapose historic written accounts of the Russian Front during World War II with visual fiction.27 In his studio Levinthal created a battleground of toy soldiers that he photographed with a minimum depth of field. He printed his negatives on Kodalith paper to emphasize atmospheric effects and emotional content. Then, he and Trudeau merged the grainy photographs with archival materials. The result departs from that of purely documentary information in that it is a visceral, psychological representation of the Nazi invasion of Russia that triggers memories of memories. Levinthal and Trudeau have produced a collective narrative that confounds feelings of legitimacy and fiction and challenges the way photography creates, recreates, and/or buttresses a particular history.

Some artists who use handmade photography approach time on a more personal than historic scale, as in the manner of Marcel Proust. In attempting to regain his personal past, Proust was acutely aware of both the instability of memory and its importance in defining ones’ position in the world. Proust comprehended the volatility of time and our tentative grasp of it. Many artists who have worked with handmade photography, such as Mike and Doug Starn, have a similar understanding. The Starns reject the notion that a moment in time can be grasped or that time is neatly linear. They construct their photographs in a way that embraces the fluidity of time. This can be seen in Double Rembrandt with Steps, 1987, which hints that the past can easily invade the present. The Starns also comment on the force of time on photographs themselves. Photographs may resurrect the past, but as the Starns so emphatically demonstrate with their splash toned, Scotch-taped images mounted with push pins; photographs themselves are fragile objects with limited life spans.

Other artists use handmade methods to explore the mutability of reality in the broadest sense. Holly Roberts lived in the Zuni Pueblo during the 1980s where she found that the Zuni belief in multiple realities—such that a person might be transposed into an animal—reinforced her own intuitive beliefs. Roberts paints her photographs in her quest to open a path that treads a line between mystery and realism. This method gives her the option to use the authenticity of the photographic rendition of reality or to oppose or parallel it with her painting. Roberts says, “My unconscious intelligence directs my hands to tell the materials where to go. It allows the emotional/spiritual channels to open up. This does not happen because we think about, explain it, or conceptualize it. It occurs because we put our hands in it and that act takes us somewhere else.”28

An on-going modernist critique of handmade photography holds that it is not pure; it mixes photography with techniques that belong to other media. But for the photographers who practice handmade techniques, this is precisely the point. Their purpose is to reveal the other self, not the one we present in daily life, but the one that passionately represents our phantasmagoria. Their methods suit their purpose. If they are to challenge and expand the standards that define visual reality, then they cannot be expected to stop at the boundaries of a medium out of consideration for its purity. In their eagerness, indeed delight, in mixing media, handmade photographers embrace the postmodern view that purity is not possible and that to pursue it is misguided dogma.

Robert ParkeHarrison and Vik Muniz are exemplary in their energetic combination of photography with other media. Harrison combines painting, photography, sculpture, and theater to speak about the human relation to the land. He depicts the attempts of a character in a black suit (played by Harrison) to save or rejuvenate nature with Rube Goldberg-like machines that Harrison has constructed from discarded junk. Despite the sense of futility and irony in his images, ParkeHarrison says: “I attempt to represent the archetype of the modern man and draw the viewer into the scene without dictating a message or the outcome of the myth presented.”29

Muniz works with everything from chocolate, to dust, garbage, ketchup, sewing thread, skywriting, sugar, and syrup. For him art is about ascertaining new ways to say things. “There’s no way to discover without being involved in the making of it,” says Muniz, “and through the process, you start to realize the mechanics of representation.”30 Muniz collected dust from the Whitney Museum of Art galleries to make drawings based on installation photographs of Minimalist and Postminimalist art that had been exhibited there. He then photographed his dust drawings to produce representations of representations. His intent was to confront the issues of originality and reproduction. Muniz’s art is about the contrivances for transmitting reality rather than an idea of reality itself. He follows the belief that only after art rids itself of the responsibility of duplicating reality is it possible for art to say something.

Digital imagery has furthered acceptance of the fundamental ideas of handmade photography, that the photograph is not necessarily authentic and that it may legitimately be manipulated to express a range of ideas. But the ease with which computers have allowed photographers to realize their aims brought about, at first, a decrease in the use of handmade techniques. More recently, however, there has been a reaction to digital image making and a return to handmade techniques. One of the special attractions of handmade techniques over digital algorithms is that when one manually engages in the production of art, one may allow the physical doing itself to determine the appearance and meaning of the outcome. This disparity between handmade and digital methods has led some to suggest that they are so different that they should be considered as entirely separate ways of working, even if they can produce similar results. Be that as it may, more artists are experimenting with hand processes now than in any time since the late 1980s.31 In addition, more commercial galleries and museums are including non-traditional forms of photography in their exhibitions and collections.

In spite of post-modernism’s assault on the myth of authorship and its sardonic outlook regarding the human spirit, artists who produce handmade photography continue to believe that individuals can make a difference, that originality matters, and that we learn and understand by doing. They think that a flexible image is a human image, an imperfect and physically crafted one that possesses its own idiosyncratic sense of essence, time, and wonder. Their work can be aesthetically difficult, as it may not provide the audience-friendly narratives and well-mannered compositions some people expect. But sometimes this is necessary to get us to set aside the ordained answers to the question: “What is a photograph?” and allow us to recognize photography’s remarkable diversity in form, structure, representational content, and meaning. This acknowledgment grants artists the freedom and respect to explore the full photographic terrain, to engage the medium’s broad power of inquiry, and to present the wide-ranging complexity of our experiences, beliefs, and feelings for others to see and contemplate.

1 See Lee Marks, New Realities: Hand-Colored Photographs 1839 to the Present, (Laramie: University of Wyoming Art Museum, 1997). - return to text -

2 See Heinz K. and Bridget A. Henisch, The Photographic Experience 1839 – 1914: Images and Attitudes. (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994). This book features a wide range of nineteenth century handmade images from the unusual “his” and “hers” funerary urns with the pictures of the occupants (p. 145) to the more common tinted daguerreotype postmortems (pp 180 – 181).- return to text -

3 See Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (New York: Bantam, 1968).- return to text -

4 See Joel Eisinger, Trace & Transformation: American Criticism of Photography in the Modernist Period (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), particularly Chapter 2, Straight Photography, pp 52 – 78.- return to text -

5 The Museum of Modern Art did not publish a catalogue for this show. However, Bunnell’s comments are available in Peter C. Bunnell, “Photography As Printmaking,” in Peter C. Bunnell, Degrees of Guidance: Essays on Twentieth-Century American Photography (Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), and 153 –154.- return to text -

6 Peter C. Bunnell, “Photography Into Sculpture,” in Peter C. Bunnell, Degrees of Guidance: Essays on Twentieth-Century American Photography (Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 164.- return to text -

7 Ibid.- return to text -

8 At that time Prince was teaching with Jerry Uelsmann at the University of Florida, Gainesville.- return to text -

9 This could be seen in the large numbers of young people experimenting with mind-altering drugs, practicing transcendental meditation, yoga, and Zen, pursuing alternative life-styles in communes as part of the “back to the land” movement, resisting the draft, and forming radical groups such as the Black Panthers and Students for a Democratic Society.- return to text -

10 Jerry N. Uelsmann, “Post-Visualization,” (1967), www.uelsmann.net, 10/17/02.- return to text -

11 Fichter also worked at the George Eastman House in Rochester as an assistant curator of exhibitions from 1966 – 1968.- return to text -

12 Robert W. Fichter, Florida Photogenesis: The Work of Creative and Experimental Photographers in Florida (Tallahassee: Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts, 2000), n.p.- return to text -

13 Robert Fichter, e-mail correspondence with the author, November 15, 2001.- return to text -

14 Another influence on some of artists discussed in his article was the Institute of Design in Chicago where Thomas Barrow, Judith Harold-Steinhauser William Larson, and John Wood went to school. It was founded by László Moholy-Nagy as the New Bauhaus (it later became the School of Design and finally the Institute of Design) and its philosophy favored an open and experimental approach to photography. For more information see David Travis and Elizabeth Siegel (eds.), Taken by Design: Photographs from the Institute of Design, 1937 – 1971 (The Art Institute of Chicago in association with The University of Chicago Press, 2002).- return to text -

15 Another aspect of this phenomenon was the founding of photographic centers, such as The Friends of Photography in Carmel, CA (1967 – 2001), by artists trying to expand the ways in which photography was practiced, taught, and viewed. This alternative arts movement got a boost in the early 1970s when the National Endowment for the Arts provided general operating grants for newly founded artist-run organizations such as CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY, Light Work, Syracuse, NY, SF Camera Work, San Francisco, CA, and Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, NY. The impetus of these new not-for-profit spaces was to provide venues where artists could create and present new art and spread new ideas that were being neglected by museums, commercial galleries, and universities. Because this kind of exhibition space was dependent on grant money, they tended to be under funded and their very existence uncertain from year to year. Consequently, their often-daring exhibitions rarely attracted the attention of the national arts media, and the exhibition venues were seldom able to afford to publish catalogues, which give exhibitions their credibility, afterlife, and a wider influence. While researching this essay I encountered a dearth of published resources.- return to text -

16 John Wood, e-mail to the author, September 25, 2001.- return to text -

17 Both Uelsmann and Bunnell began a life-long friendship while attending Rochester Institute of Technology. Uelsmann received his BFA in 1957 and Bunnell earned his BFA in 1959. Many artists who lived, studied, and worked in Rochester during the late 1960s and early 1970s would fan out and carry these influences across the country.- return to text -

18 Kwik-Print (now defunct) was a derivative of Kwik Proof, an off-press color proofing process used in the graphic arts industry, which was marketed by Light Impressions. After Breaking the Rules, a number of others published that revived interest in “obsolete” and non-traditional processes, William Crawford, The Keepers of Light: A History & Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Morgan & Morgan, 1979), Jim Stone, ed. Darkroom Dynamics: A Guide to Creative Darkroom Techniques (Marblehead, MA: Curtin & London, 1979) and Robert Hirsch, Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Ideas, Materials & Processes (Boston: Focal Press, 1991).- return to text -

19 Kodak Kodalith paper was a thin, matt, orthochromatic graphic arts paper that was not intended for pictorial purposes. However, when it was used for pictorial expression its responsiveness to time and temperature controls during development enabled one to produce a wide range of grainy, high-contrast, and sepia tonal effects. Its unusual handling characteristics also meant that photographers had to pull the print at precisely the “right” moment from the developer and quickly get it into the stop bath, making each print unique.- return to text -

20 Other unique images from this series incorporated paint and markers, collage materials, and appropriated images.- return to text -

21 See Lucas Samaras, essay by Arnold B. Glimcher, Photo-Transformations (California State University, Long Beach and E. P. Dutton, New York, 1975).- return to text -

22 Haptic comes from the Greek haptos, which means laying hold of. Those with a haptic sensibility are concerned with their bodily sensations and subjective experiences. Haptically inclined artists make themselves part of the picture. See Victor Lowenfeld and W. Lambert Brittain, Creative and Mental Growth. (NY: Macmillan Publishing Co., 6th ed., 1970.- return to text -

23 Robert Flynt, e-mail correspondence with the author, December 1 & 4, 2001.- return to text -

24 The date and dimensions of this piece may vary as it was originally produced on a black gallery wall, making each installation unique. A permanent version is in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Pat Ward Williams, phone conversation with author, October 15, 2002.- return to text -

25 Although Kellner did not study photography, she did receive her MFA from RIT in 1974.- return to text -

26 Tatana Kellner, e-mail correspondence with author, July 19, 2002.- return to text -

27 See David Levinthal and Garry Trudeau, Hitler Moves East: A Graphic Chronicle, 1941 – 43 (Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977).- return to text -

28 Holly Roberts, telephone conversation with author, November 30, 2001.- return to text -

29 Robert ParkeHarrison, written correspondence with author, April 3, 2000.- return to text -

30 Vik Muniz, “Ars Brevis,” New York Times Sunday Magazine, February 11, 2001, www.nytimes.com.- return to text -

31 This mini-Renaissance can be seen in the flurry of commercial book publishing that includes Christopher James, Book of Alternative Photographic Processes (Albany: Delmar/Thomson Learning, 2002); John Barnier, Coming into Focus: A Step-by-Step Guide to Alternative Photographic Printing Processes (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000); and a second edition of Robert Hirsch and John Valentino Photographic Possibilities: The Expressive Use of Ideas, Materials & Processes (Boston: Focal press, 2001).- return to text - |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|